Saudi Arabia's wants to build a 105-mile-long 'Line' city in the desert

Saudi Arabia's linear city relies on technology that doesn't exist yet.

Saudi Arabia has a bold vision for its newest city: a 106-mile-long (170 kilometers) "Line" without cars or long commutes. But urban design experts are skeptical, to say the least.

"Awful. Nightmare," said Emily Talen, an urban design researcher at The University of Chicago.

Despite the flashy announcement of The Line, the technology for such a city doesn't exist yet, and building massive new cities from scratch is fraught with challenges.

"The history of so-called megaprojects is not pretty," said Stephen Wheeler, a landscape architect and environmental design professor at the University of California, Davis. "Usually, they don't quite turn out the way the original visionaries intend, they often fall prey to economic conditions or other people's ideas of what should happen, or they wind up costing vastly more than expected."

Design of the line

So far, The Line exists only as a website and a press announcement made by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on Jan. 10. The proposal calls for the aforementioned 106-mile strip of development in Neom, a planned city in northwestern Saudi Arabia. The Saudi government touts the area as undeveloped, but it is in fact home to 20,000 members of the Huwaitat (also spelled Howeitat) tribe, who have protested being evicted for the planned megacity, according to The Guardian.

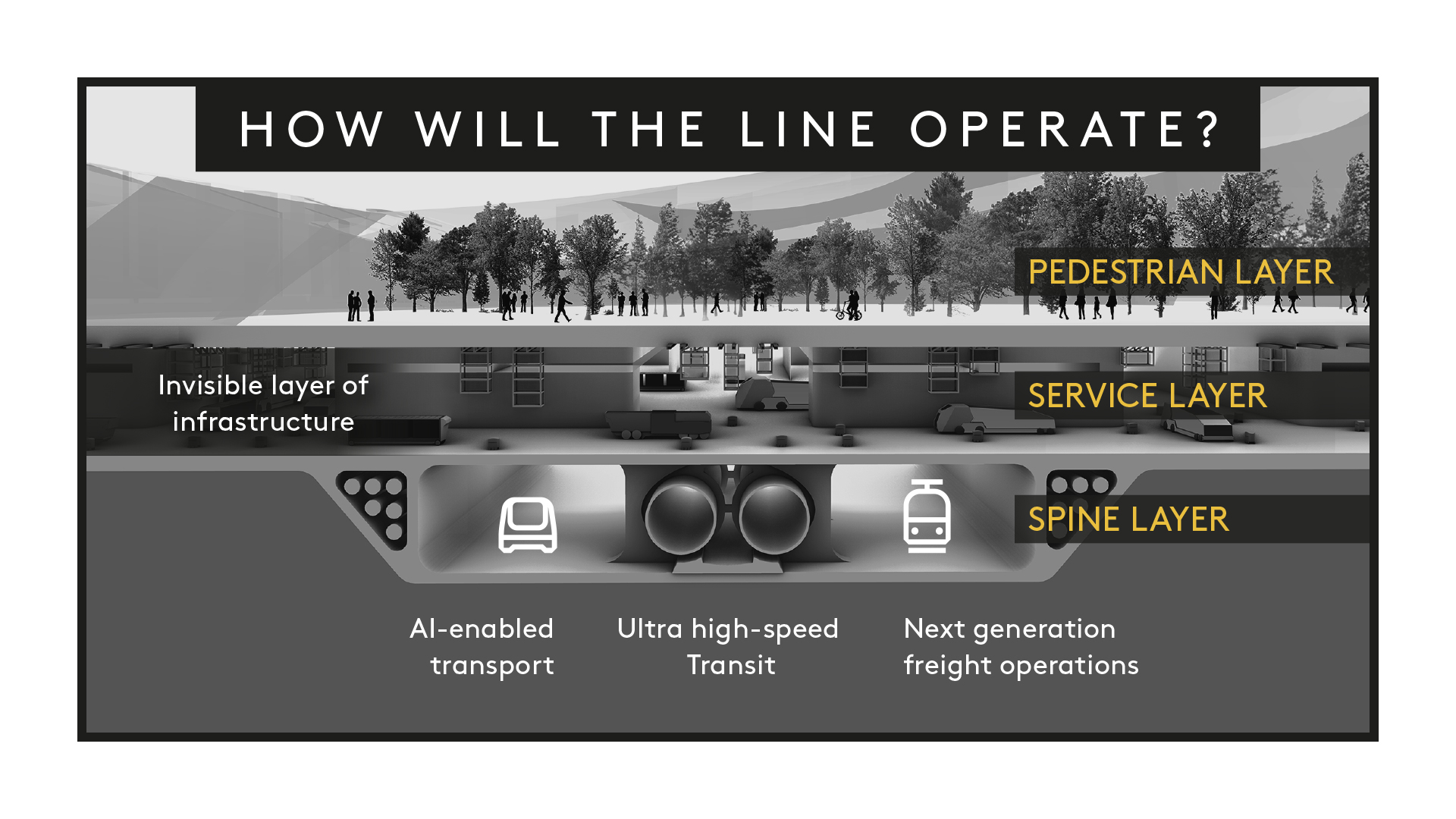

The Line would be built in three layers: a surface-level pedestrian layer full of parks and open spaces, a lower "service" layer and an even deeper transportation "spine" that would consist of "ultra-high-speed transit." The proposal claims that all daily services would be walkable within 5 minutes of each node on the line and that commutes between nodes on the high-speed transit would take no more than 20 minutes.

According to some experts, however, those goals are unfeasible. The plan for a miles-long line with a width that can be walked in only 5 minutes is questionable, said Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, a professor of architecture at the University of Miami and a founding partner at DPZ CoDesign, an urban design and architecture firm. To support that level of public transport, Plater-Zyberk told Live Science, the line would require larger nodes capable of holding more people.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If there's only a few hundred people at every stop, you're not going to economically sustain that investment in that infrastructure," she said.

Keeping The Line linear would also require heavy regulation, Plater-Zyberk said, as cities tend to expand outward as they grow. This is why "hub-and-spoke" transit systems tend to be more common; they allow arms of transit to connect to one another without requiring travel all the way back to a central transit station. Even as they advance promising ideas such as walkability, The Line's designers seem to dispense with historical knowledge about what works well when designing transit, Plater-Zyberk said.

"There are many people now worldwide who could assist in elaborating the idea to make it workable," she said. "We have data on what kind of support transit systems need in order to be sustainable."

However, it's also unclear if the technology for The Line's transit system exists yet. Traveling 106 miles in 20 minutes would require a speed of 318 mph (512 km/h), which outpaces high-speed rail by a long shot. Eurostar trains in Europe travel at about 199 mph (320 km/h); and while some of China's high-speed rail trains reach speeds of 236 mph (380 km/h, in practice, they average about the same speeds as Eurostar. Underground Hyperloop pods, like those in development by Virgin and SpaceX, could theoretically manage the journey, but that technology is still at least a decade away from use. The fastest Hyperloop tests so far have topped out at 288 mph (463 km/h) without passengers. Only one company, Virgin, has tested the technology with passengers, at speeds of 107 mph (172 km/h).

Planning cities

If the future of tech is a problem for The Line, so is the past. The Saudi proposal isn't the first time a linear city has been suggested. In 1882, Spanish urban planner Arturo Soria y Mata proposed the Ciudad Lineal, or Linear City, which would start with a railway or roadway and have all buildings and other parts of the city constructed along this line. The district of Ciudad Lineal in Madrid was built with this idea in mind, and its main thoroughfare is named after Soria y Mata — but the neighborhood does not stand alone from the rest of Madrid.

"It just kind of became sprawl," Talen told Live Science.

Brasilia, the capital of Brazil, was originally planned as the ideal city, shaped like an airplane with government buildings lining the fuselage. But Brasilia has been criticized as not particularly livable, with few mixed-use neighborhoods and little housing within the city center for lower-income families. This meant long commutes for many who worked in the city.

"Usually, we're far better off making thoughtful incremental improvements to existing cities than trying to design entirely new cities from scratch," Wheeler told Live Science. Often, when communities are planned from scratch, "we wind up with kind of a sterile, master-planned community that doesn't have the richness of something that evolves over time."

A far more sustainable strategy, Talen said, is to fix existing cities.

"Should all these resources be spent on building anew in the middle of a desert?" Talen said. "How does that make sense when you have plenty of urban problems all around you that need repairing?"

What's more, many pie-in-the-sky built-from-scratch cities cater not to locals, but to tourists or second-home owners. The Sustainable City in Dubai, for example, is touted as the first net-zero-energy city but caters heavily to foreigners buying second homes. Similarly, The Line's press materials boast that Neom is within a 4-hour plane trip for 40% of the world's population.

"Whether that is a sustainable lifestyle is pretty debatable," Wheeler said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.