Teensy long-necked dinosaur embryo reveals weird snout horn

The 1.2-inch skull has revealed all kinds of sauropod secrets.

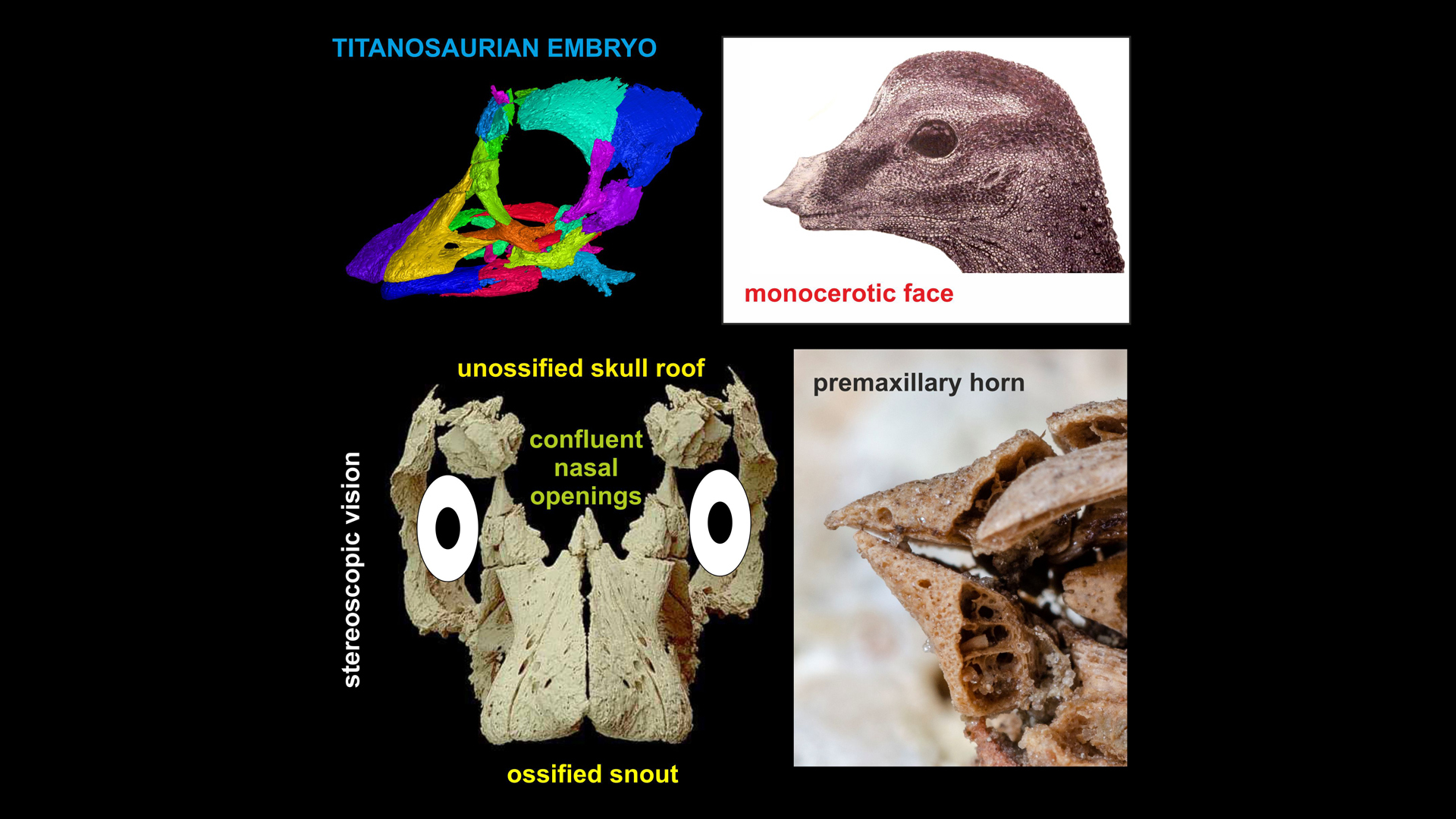

A rare dinosaur embryo that was nearly lost to science shows an unprecedented view of what a wee, developing sauropod dinosaur looked like before it hatched and grew into a humongous, long-necked plant-eating behemoth. As it turns out, this unknown species of titanosaur had a tiny, rhino-like horn on its snout that it lost by adulthood, a new study finds.

The nearly intact skull is all that's left of the 80 million-year-old embryo, but reveals this wee horn in incredible detail. It's possible the titanosaur used this horn to peck out of its egg, the researchers said, although they also had other ideas about how it broke free from its shell.

The 1.2-inch-long (3 centimeters) skull also shows that unlike adult titanosaurs, this young titanosaur had binocular vision, which would have helped it find food and detect danger — "a great advantage, especially when we take in account the fact that they could not rely on parental care," study lead researcher Martin Kundrát, a paleobiologist at Center for Interdisciplinary Biosciences at Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in the Slovak Republic, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Image gallery: Dinosaur day care

"This is one of the nicest dinosaur skulls found preserved inside its egg," Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor of dinosaur paleobiology at the University of Calgary in Canada who wasn't involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "Because of their small size and softer bone, the skulls of baby dinosaurs tend not to fossilize nearly as well (as larger dinosaurs). They tend to fall apart or get crushed easily."

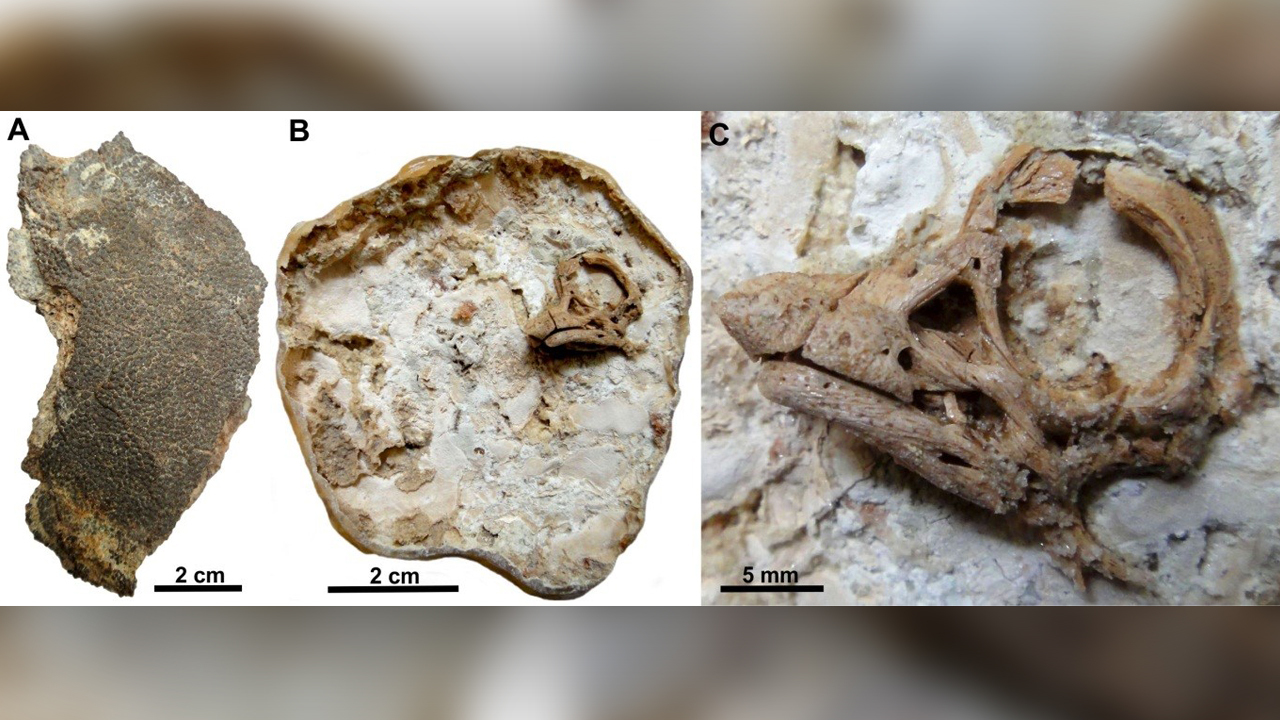

Researchers almost missed the opportunity to analyze this one-of-a-kind skull. The fossilized egg had been smuggled out of Argentina, where it was originally found, and sold in 2001 by an Argentine dealer at an auction in Tucson, Arizona to study co-author Terry Manning, a freelance paleontology technician. Manning prepared the egg with his self-developed, acid-etching technique — a chemical method that etched away just 10 micrometers of the rock a day. This revealed the previously hidden skull inside; the first recovered 3D embryonic skull of a sauropod on record.

Manning was actually planning to sell the embryo at another auction, according to the journal Nature, but he agreed to repatriate the specimen, and now the fossil is part of the collection at the Carmen Funes Municipal Museum in Neuquen Province, in northwest Patagonia, Argentina, according to the new study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is good news that this important specimen, which was illegally exported from Argentina, found its way back to a museum setting where it can be properly curated and studied," Kristina Curry Rogers, a paleontologist at Macalester College in Minnesota who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

Egg-ceptional specimen

Titanosaur embryos are rare, but this specimen isn't the only one. Some 25 years ago, flattened titanosaurian embryos discovered from Cretaceous age rocks at Auca Mahuevo, Patagonia, also revealed that these embryonic dinosaurs had horns. This prompted some scientists to suggest that the horn was used as a tool to help titanosaurs hatch out of their eggs.

"However, I have some doubts on this interpretation," Kundrát said. Some modern reptiles and birds are equipped with an egg tooth made out of keratin (the same substance as fingernails) that sticks upward, like a tiny pick ax from their snouts. The horn on the embryonic titanosaurs, however, projects forward from the snout, meaning it was parallel with the inner surface of the shell. Given that the titanosaur was likely curled up in its egg, like modern reptile embryos develop today, "I have difficulties imagining how it could work," Kundrát said.

Instead, perhaps the developing titanosaur used its powerful legs to crack the eggshell, he said. Or maybe it had an egg tooth (that was separate from the horn) that grew on top of its snout, the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: Album: Discovering a duck-billed dino baby

Nearly hatched?

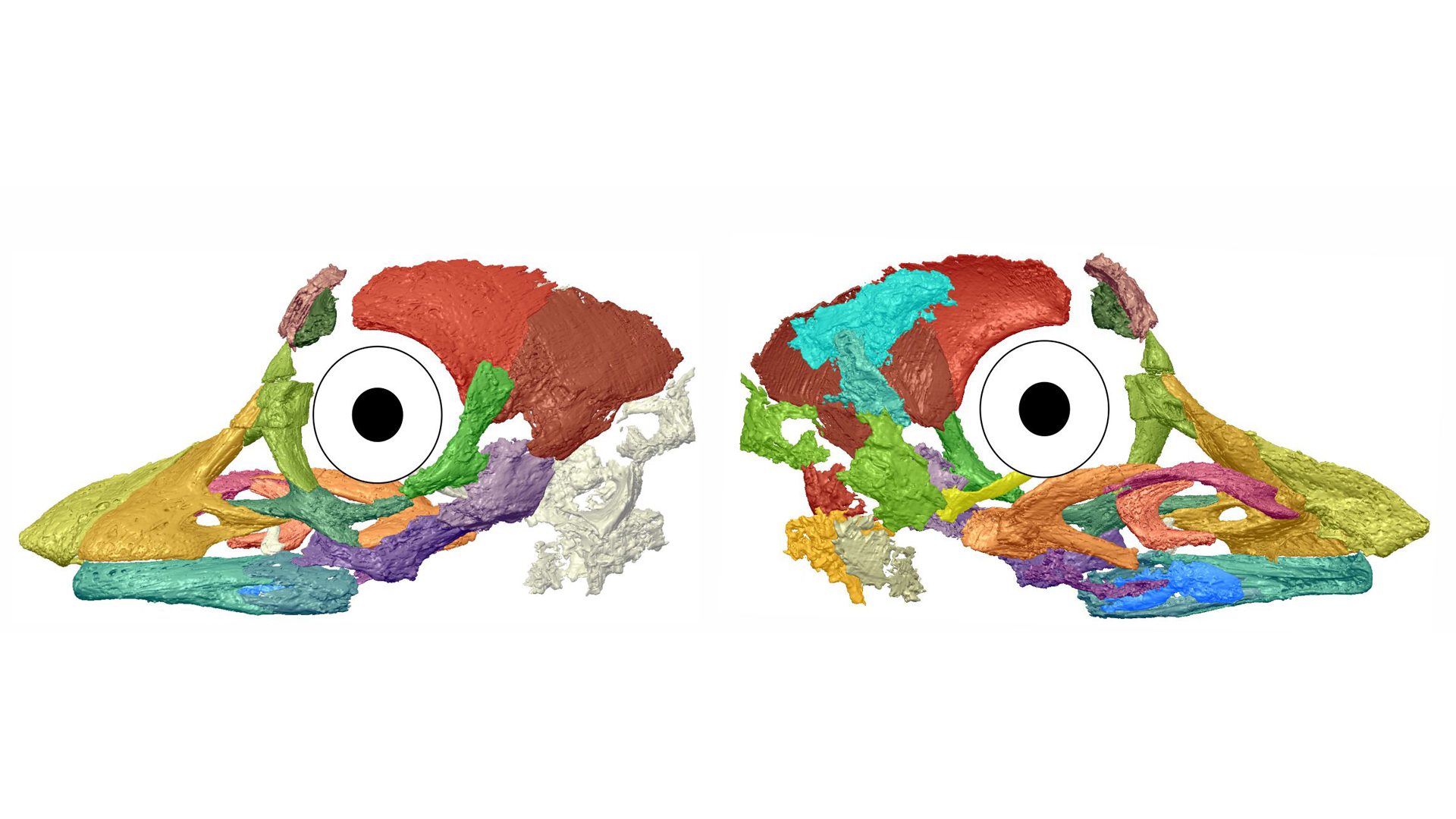

Figuring out the developmental age of the tiny titanosaur was not an easy task. However, the researchers used a high-tech scanning method at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, which allowed them to reconstruct the fossil as a digital 3D image.

By comparing the development of the dinosaur's braincase (the part of the skull that held the brain), with the rest of the skull, and comparing this "neurocranial incompleteness" with the skulls of embryonic crocodiles, which are distant relatives of dinosaurs, Kundrát found that the baby dinosaur had already undergone four-fifths (80%) of its embryonic development, he said.

In other words, it was nearly hatched.

This nearly-ready embryo was hard at work, preparing for life outside its egg. In modern reptiles, for instance crocodiles, the developing creature gets calcium for its skeleton from the egg yolk and shell. While analyzing the titanosaur's eggshell, the scientists found "large pits" that merged onto the remnant of a fibrous membrane, a structure that helps embryos reabsorb calcium, Kundrát said.

This finding is the first known evidence that titanosaurian embryos used eggshell-derived calcium, the researchers said.

In addition, by analyzing the different proportions of the skull, the researchers found that the teeny dinosaur already had an elongated snout and drawn back nose openings. Earlier studies have suggested that these features appeared when titanosaurs were juveniles, but they "are, in fact, already present in the [newfound] embryo prior to hatching," the researchers wrote in the study.

Other aspects of the baby titanosaur may remain a mystery. For example, it's not clear exactly where in Patagonia the poached egg was found. However, its eggshell is thicker and the fossil has a different geochemical signature than the known titanosaur embryos from Auca Mahuevo, so perhaps there's "an unknown egg locality with exceptional preservation of embryos," still out there, Kundrát said.

Despite this missing information, it's remarkable how much data this fossil revealed, as it "shows us the smallest stages of growth of some of the largest known dinosaurs," Zelenitsky said. "These dinosaurs were pretty tiny at hatching, breaking out of an egg smaller than a volleyball and eventually growing into adults that weighed dozens of tons. This change in size would be similar to a human being born the size of a jelly bean or less."

The study was published online Aug. 27 in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.