Why are thousands of stinging jellyfish crowding the Rhode Island coast?

Watch out, those stings can hurt.

Thousands of jellyfish are gathering by the coast of Rhode Island, and they're not afraid to use their stingers against potential foes, according to news sources.

The jellyfish, known as Atlantic sea nettles (Chrysaora quinquecirrha), thrive in warm waters, which may partially explain the recent population boom over the past month, the Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife Outdoor Education (RIDEM) posted on Facebook. After all, June 2021 was the hottest June on record in North America, according to the European Union's Copernicus program, Live Science reported.

Even so, scientists are puzzled over the cause of the spike. The jellyfish swarms are popping up at a coastal lagoon known as Ninigret Pond and a saltwater lagoon estuary called Green Hill Pond, near the coast. "Their high abundance in the ponds this summer is not fully understood," RIDEM wrote in the post, adding that "their numbers are expected to decline as the summer goes on."

Related: Image gallery: Jellyfish rule!

Swimmers would be wise to avoid the jellies, the RIDEM noted. "Although their sting is not fatal (unless there is a severe allergic reaction), it can cause moderate discomfort and itchy welts," RIDEM representatives wrote in the post.

If you are stung by an Atlantic sea nettle, there are some steps you should take, the RIDEM noted. First, remove any visible tentacles from the affected area with a gloved hand or plastic bag. Then, rinse the sting with vinegar, store-bought sting spray or (in a pinch) saltwater, but not freshwater, "as this can worsen the sting," RIDEM representatives wrote. Moreover, because heat can inactivate the venom, the RIDEM recommended applying a hot pack or hot water to the sting. After that, "an ice pack and hydrocortisone cream can be applied to help with discomfort," the RIDEM noted, adding that you should seek professional medical care if symptoms worsen.

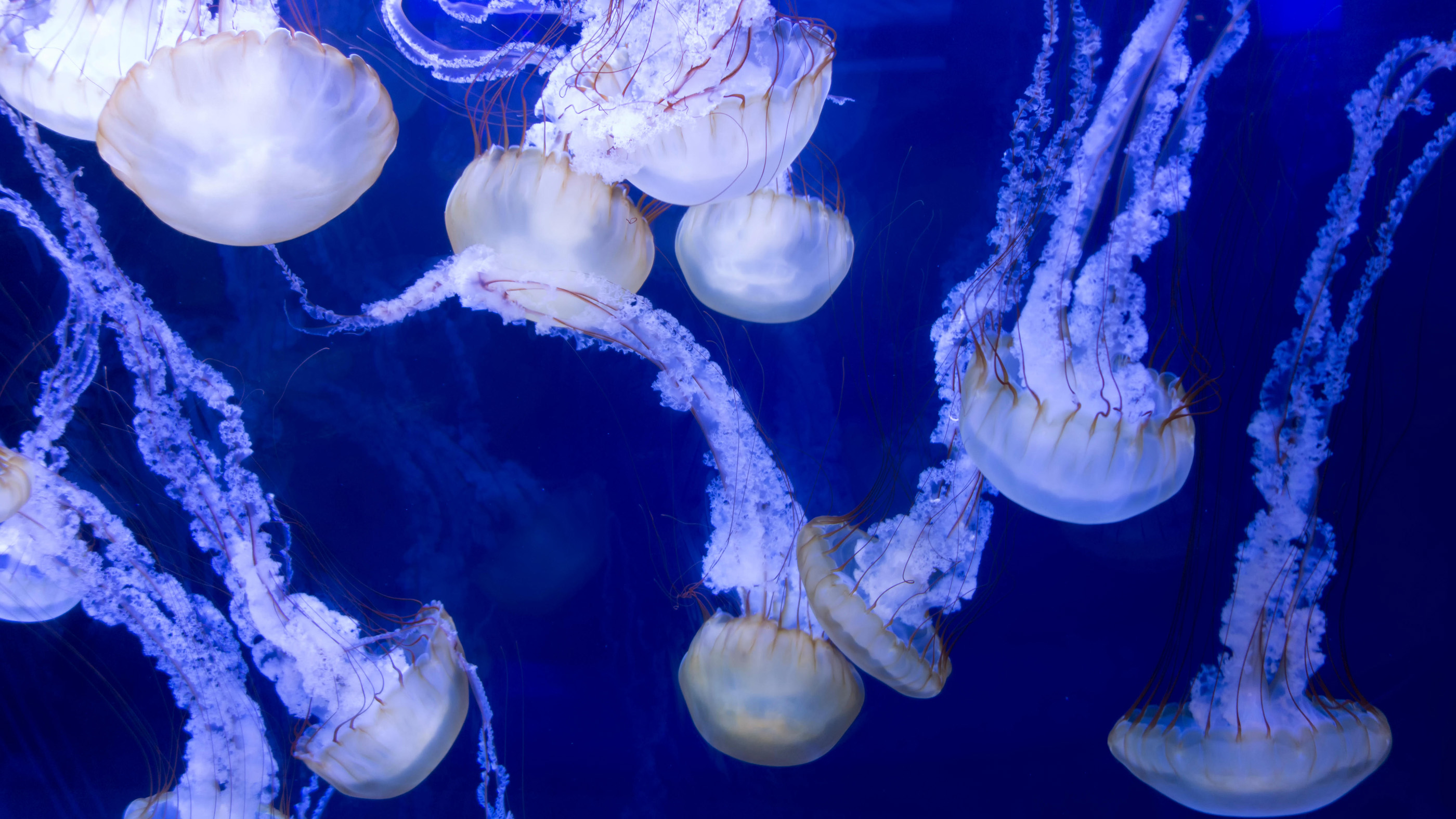

Atlantic sea nettles are found along the U.S. East Coast, from Cape Cod in Massachusetts to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, according to the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California. This sea creature has a saucer-shaped medusa (the "bell" part of the body); four thick, long, lacy arms; and between four and 40 long, thread-like tentacles, the aquarium reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These jellyfish vary in color, depending on their habitat. Atlantic sea nettles in the Chesapeake Bay and the open ocean tend to be pink to reddish-maroon, with red stripes that point toward their yellow tentacles, while jellies in the low-salt waters of estuaries have white bells and no stripes, according to the Aquarium of the Pacific.

The jellies' bells vary from 4 to 8 inches (10 to 25 centimeters) in diameter. They gobble up ctenophores (comb jellies), as well as young minnows and other small fish, mosquito larvae, bay anchovy eggs, and copepods and other zooplankton, according to the Aquarium of the Pacific.

Few predators, save for sea turtles, prey on Atlantic sea nettles, so their numbers are largely influenced by rain and heat, according to an article in Save the Bay magazine, which focuses on the Chesapeake Bay. These jellies prefer warm, salty water, so their populations tend to spike during dry and hot summers, the magazine reported.

Jellyfish blooms aren't a rare event, especially in summertime. Overfishing has led to fewer predators that compete with and prey on jellyfish, and nutrient-rich pollution, such as runoff water full of fertilizer, can lead to phytoplankton blooms, creating an all-you-can-eat buffet for jellies, Live Science previously reported.

However, the overarching reasons behind jellyfish blooms are likely more complex, a 2012 study published in the journal BioScience found, and a 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that while human activity does appear to effect on jellyfish numbers, jellyfish populations might also naturally rise and fall in decades-long oscillations, although more research is needed to say so for sure.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.