Long-lost bunker belonging to 'Churchill's secret army' discovered in Scottish forest

The bunker was one of hundreds built to sabotage Nazi German invaders, historians say.

Forestry workers were felling trees in southern Scotland when they noticed something peculiar among the roots and bracken: An iron door. It turns out the team had accidentally discovered a lost WWII-era bunker, built to house one of Great Britain's most secretive — and suicidal — military forces.

Known as the Auxiliary Units (or sometimes "Churchill's secret army"), the force was a corps of volunteers similar to Britain's Home Guard, charged with defending the country in the event of a Nazi German invasion. Unlike the Home Guard, however, the Auxiliary Units were a guerilla warfare brigade shrouded in secrecy. Each unit, which held up to eight men, based their operations out of one of hundreds of tiny, concrete-capped bunkers buried throughout the countryside. The locations of these bunkers were such fiercely guarded secrets that many of them still remain undiscovered today.

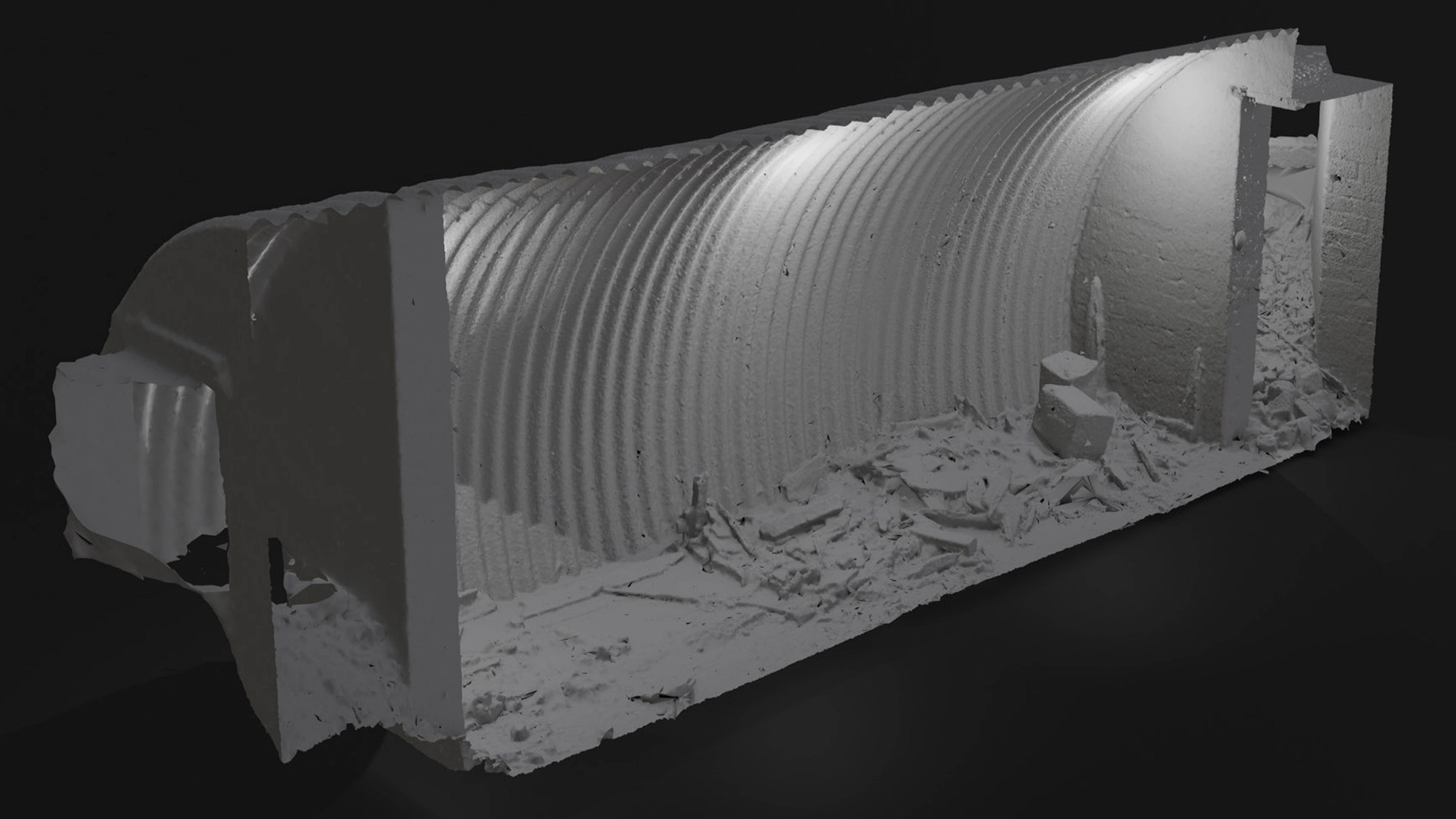

Now, one fewer of those secrets is lost to history. Forestry workers discovered the new bunker last fall in the wooded countryside south of Edinburgh, buried 4.2 feet (1.3 meters) underground at its deepest end, according to a news release from the AOC Archaeology Group, which recently surveyed the site.

Related: The 22 weirdest military weapons

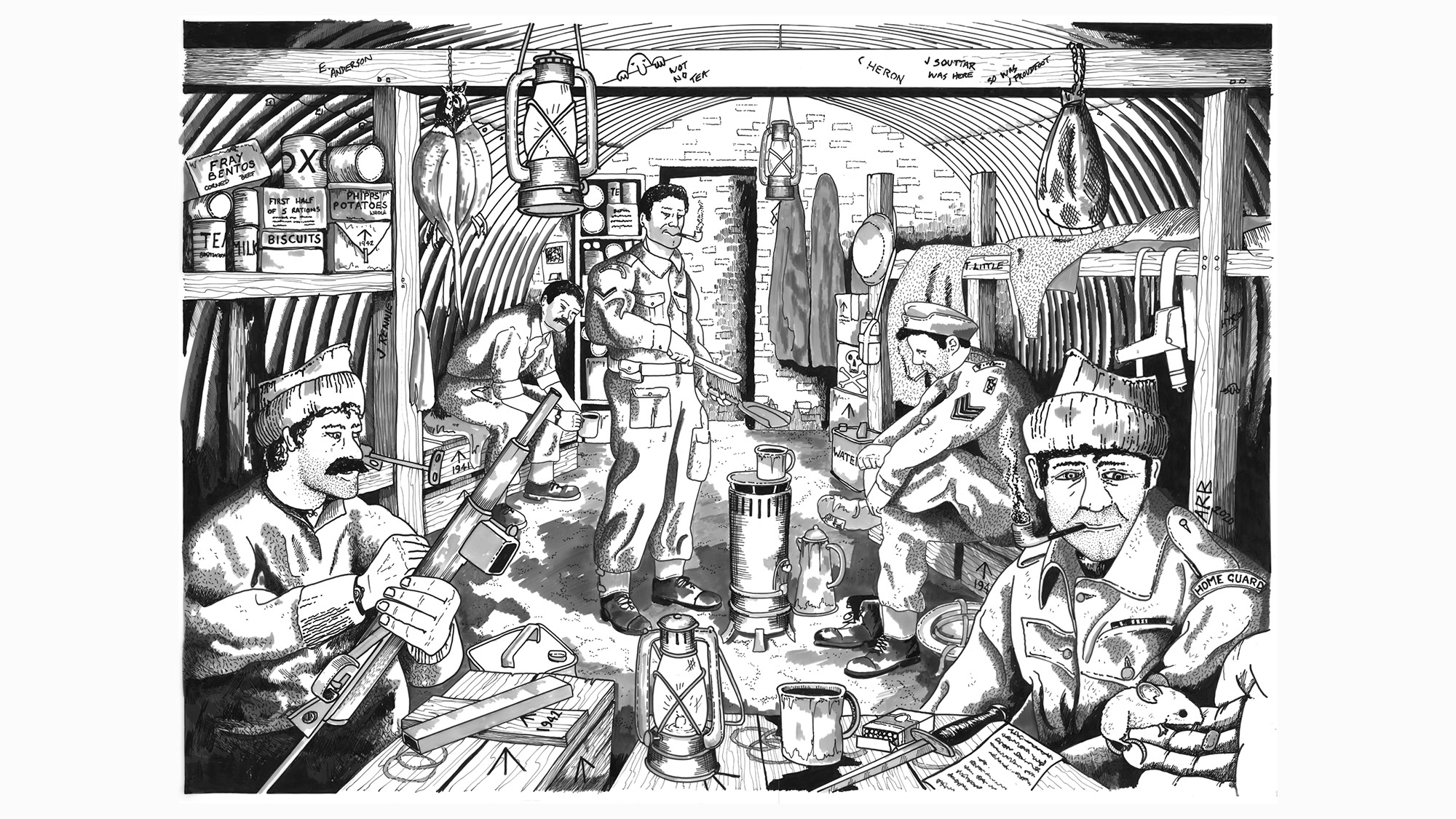

With a tin roof and brick walls, the bunker was a concrete sardine can, roughly 23 feet long and 10 feet wide (7 m by 3m) that would have housed about seven soldiers for months or years on end. The archaeologists found some wooden scraps in the bunker that may have once been a soldier's bed, plus an empty tin can that may have contained his supper.

"From records, we know that around seven men used this bunker and at the time were armed with revolvers, submachine guns, a sniper's rifle and explosives," Matt Ritchie, an archaeologist with Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS), told the BBC.

These men would have acted as an autonomous guerilla strike force during a Nazi invasion, emerging from their hidden dens to sabotage the enemy's advancement by any means necessary. The unit members — nicknamed the "scallywags" — were trained in ambushes, assassinations, demolition and, if push came to shove, suicide. According to British Resistance historian Malcolm Atkin, any given scallywag's life expectancy was just two weeks. They were expected to die fighting — and, if capture seemed likely, ordered to kill themselves and their comrades with bullets or bombs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Winston Churchill deployed the Auxiliary Units in 1940, though thankfully they never had to use their guerilla training on the home front. Eventually, as the tides of war shifted, the scallywags were redeployed as special forces during the D-Day invasion, according to the BBC.

While archeologists continue studying the newly rediscovered bunker, the site remains closed to the public. In true scallywag spirit, the bunker's precise location won't be revealed.

- 10 epic battles that changed history

- Beasts in battle: 15 amazing animal recruits in war

- 15 Incredible places on Earth that are frozen in time

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.