Rare and fragile fossils found at a secret site in Australia's 'dead heart'

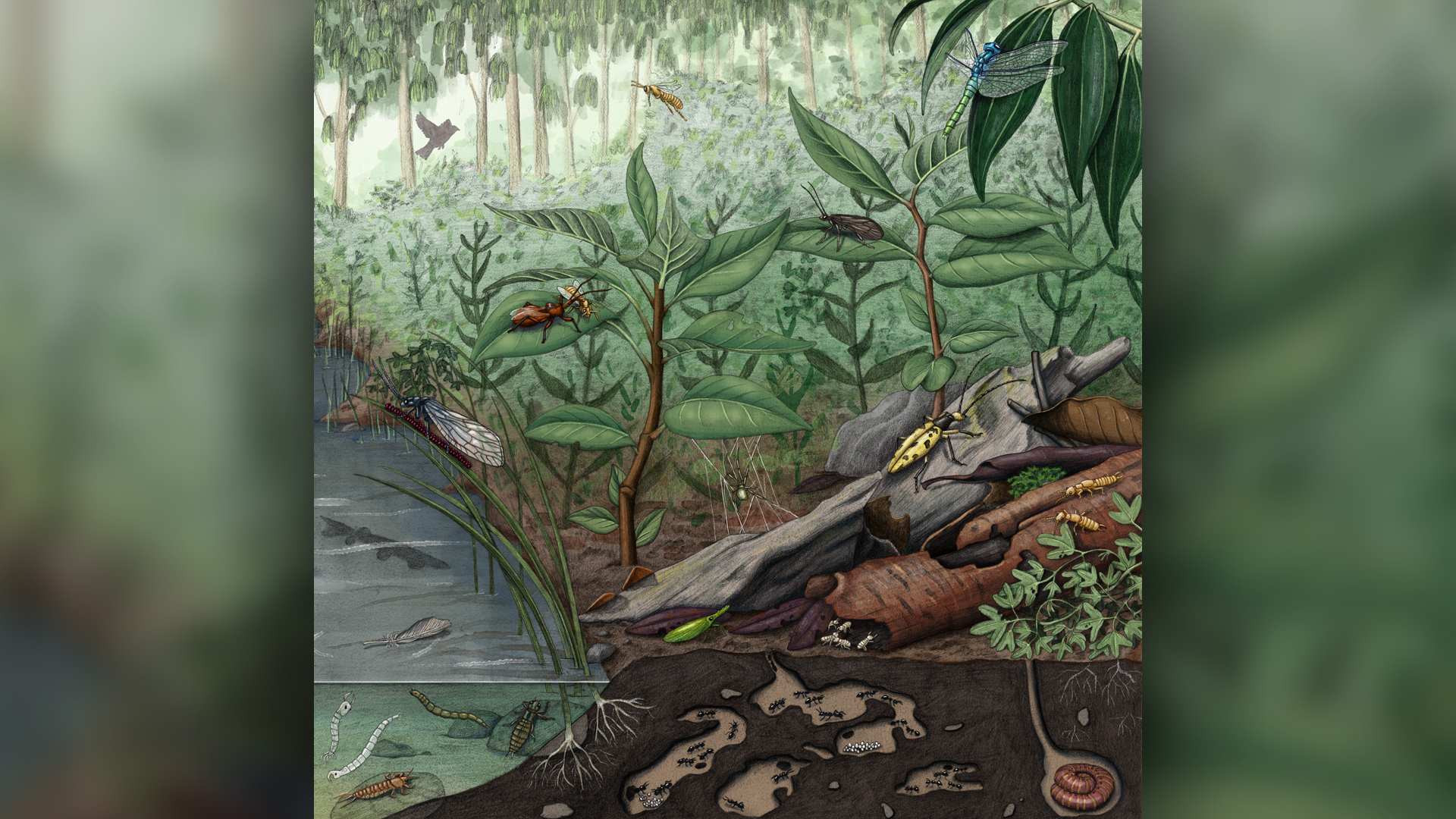

Scientists found thousands of preserved plants, spiders and insects dating to the Miocene Epoch.

Buried in Australia's so-called dead heart, a trove of exceptional fossils, including those of trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas, tiny fish and a feather from an ancient bird, reveal a unique snapshot of a time when rainforests carpeted the now mostly-arid continent.

Paleontologists discovered the fossil treasure-trove, known as a Lagerstätte ("storage site" in German) in New South Wales, in a region so arid that British geologist John Walter Gregory famously dubbed it the "dead heart of Australia" over 100 years ago. The Lagerstätte's location on private land was kept secret to protect it from illegal fossil collectors, while scientists excavated the remains of plants and animals that lived there sometime between 16 million and 11 million years ago.

The researchers unearthed remains that are unique in the Australian fossil record for the Miocene Epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), they reported in a new study. Most of the prior Miocene finds that other scientists have unearthed in Australia were bones and teeth from larger animals — which are commonly preserved in Australia's dry landscapes. However, the new cache held fossils of small and delicate creatures such as spiders and insects, as well as flora from the Miocene rainforest.

Related: 15 incredible places that are frozen in time

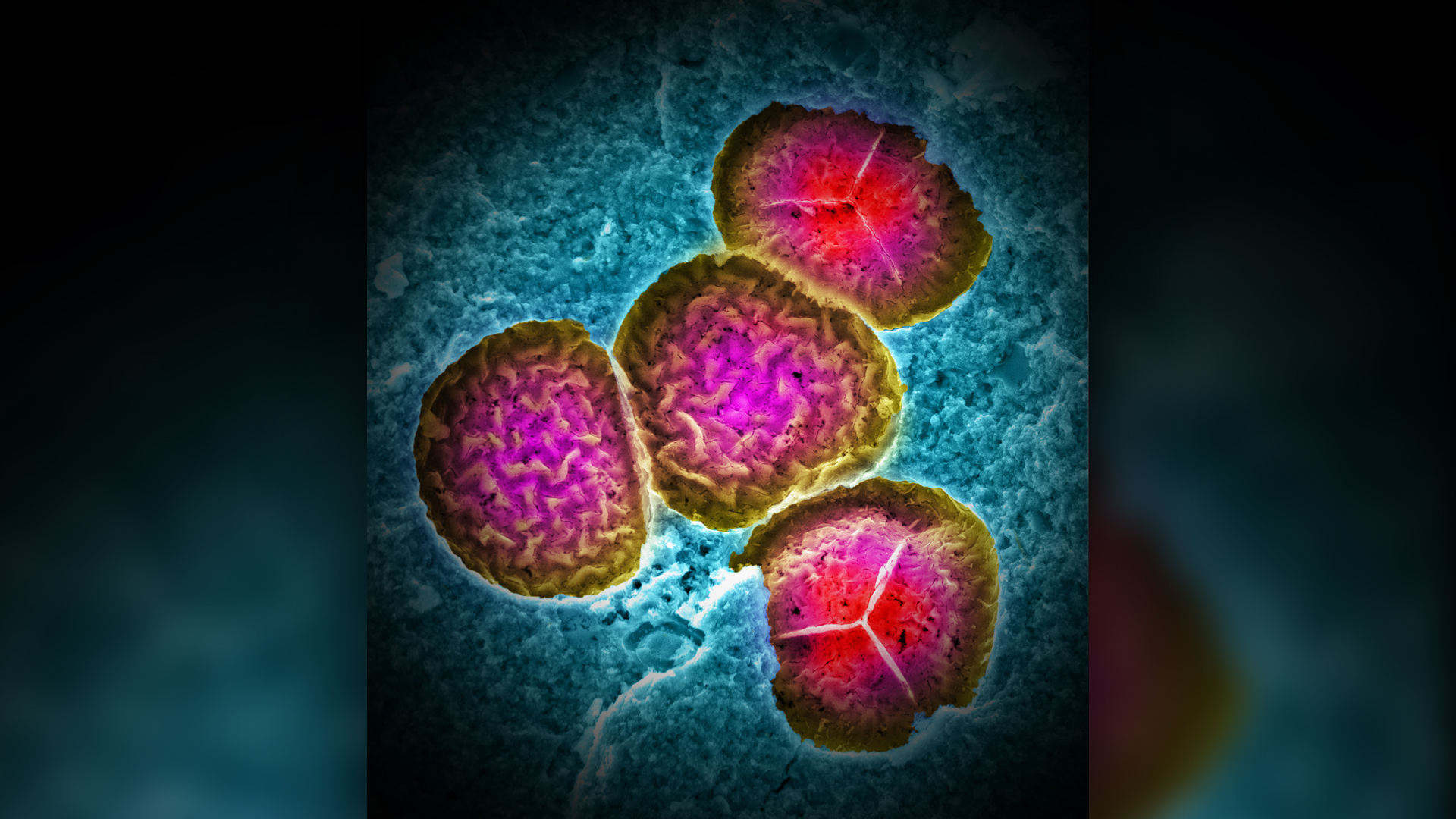

By examining the well-preserved fossils with scanning electron microscopes (SEM), the study authors were able to image details as fine as individual cells and subcellular structures. Some of the images even revealed animals' last meals, such as fish, larvae and a partially digested dragonfly wing preserved inside fishes' bellies. In other fossilized scenes, a freshwater mussel clung to a fish's fin, and pollen grains were stuck to insects' bodies.

"This site gives us unprecedented insight into what these ecosystems were like," lead study author Matthew McCurry, a curator of paleontology at the Australian Museum, told Live Science in an email. "We now know how diverse these ecosystems were, which species lived in them and how these species interacted."

Paleontologists first visited the site — now named McGraths Flat — in 2017, after a farmer reported finding fossilized leaves in one of his fields. When the scientists investigated, "we were pleased to discover that the site yields a much wider range of fossils, including the remains of insects, spiders and fishes," McCurry said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fossil-bearing rock layer measures between 11,000 and 22,000 square feet (1,000 and 2,000 square meters), and paleontologists have thus far excavated just over 500 square feet (50 square m), according to McCurry. A matrix of iron-rich rock called goethite surrounded the fossils on top of a layer of sandstone. Plants and animal remains in a stagnant pool were likely encased in iron and other minerals after runoff from nearby basalt cliffs drained into the pool, known in Australia as a billabong, which preserved them in exquisite detail.

Now, millions of years later, researchers have begun piecing together the fossils to build a portrait of an extinct Australian rainforest. They found leaves from flowering plants, pollen, fungal spores, more than a dozen specimens of fish, "a wide diversity of fossilized insects and arachnids," and a feather from a bird that was about the size of a modern sparrow, the study authors reported. Analysis of the preserved leaves suggests that the average temperature at the time was about 63 degrees Fahrenheit (17 degrees Celsius).

"I find the spider fossils the most fascinating," McCurry told Live Science. Until now, only four fossil spiders were known from Australia, and researchers have so far found 13 spider fossils at McGrath Flats, McCurry said.

Preserved soft tissues in the feather and in the fishes' eyes and skin held another exciting detail: pigment-storing cell structures called melanosomes. Though the color itself isn't preserved, scientists can compare the shape, size and stacking patterns in the fossil melanosomes to those in modern animals. In doing so, paleontologists can often reconstruct the colors and patterns in extinct species, study co-author Michael Frese, an associate professor of science at the University of Canberra in Australia, said in a statement.

While much has been discovered at McGraths Flat, "this is really only the beginning of the work on the fossil site," McCurry said. "We now know the age of the deposit and how well-preserved the fossils are, but we have years of work ahead of us to describe and name all of the species we are finding. I think that McGraths Flat will become extremely important in building a more accurate picture about how Australia has changed over time."

The findings were published Friday (Jan. 7) in the journal Science Advances.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.