7 strange snake stories from 2022

It's no surprise that snakes have always been creepy.

There's no denying that snakes are some of the most fascinating, bizarre and, yes, frightening reptiles on the planet. From an eastern kingsnake swallowing a timber rattlesnake nearly twice its size to a nasty battle between a venomous cobra and an 8-year-old boy, there was no shortage of strange snake headlines this year. Here are seven startling snake stories from 2022.

1. Cobra bites boy; boy bites it back

When a venomous cobra took a bite out of an 8-year-old boy in India after coiling around his hand, the child didn't hesitate to seek revenge on the snake, sinking his teeth into its scaly skin — twice. After the incident, the boy's parents rushed him to the hospital, where doctors deemed the injury a rare venom-free "dry bite." The child walked away unscathed and with a cool story to tell his friends. The snake wasn't quite so lucky. It died.

2. Snake chokes to death on a giant centipede

Humans aren't the only living things that bite off more than they can chew. A rim rock crowned snake (Tantilla oolitica), considered the rarest snake in North America, gave scientists a fright when they came upon the corpse of one of these elusive creatures at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park in Key Largo, Florida. Lodged in its mouth and partway down its gullet was a giant centipede, which the snake had attempted to swallow headfirst. Even though its prey was one-third its size, the snake lost the battle, succumbing to the centipede's venom.

3. Scientists excited to discover snake's clitoris

An evolutionary biologist from the University of Adelaide in Australia proved that the snake clitoris really does exist. She was the first scientist to search for it on deceased snakes in the lab and discovered it in nine snake species. It makes sense that snakes would have clitorises, given that these sexual organs are found throughout all vertebrate lineages except birds.

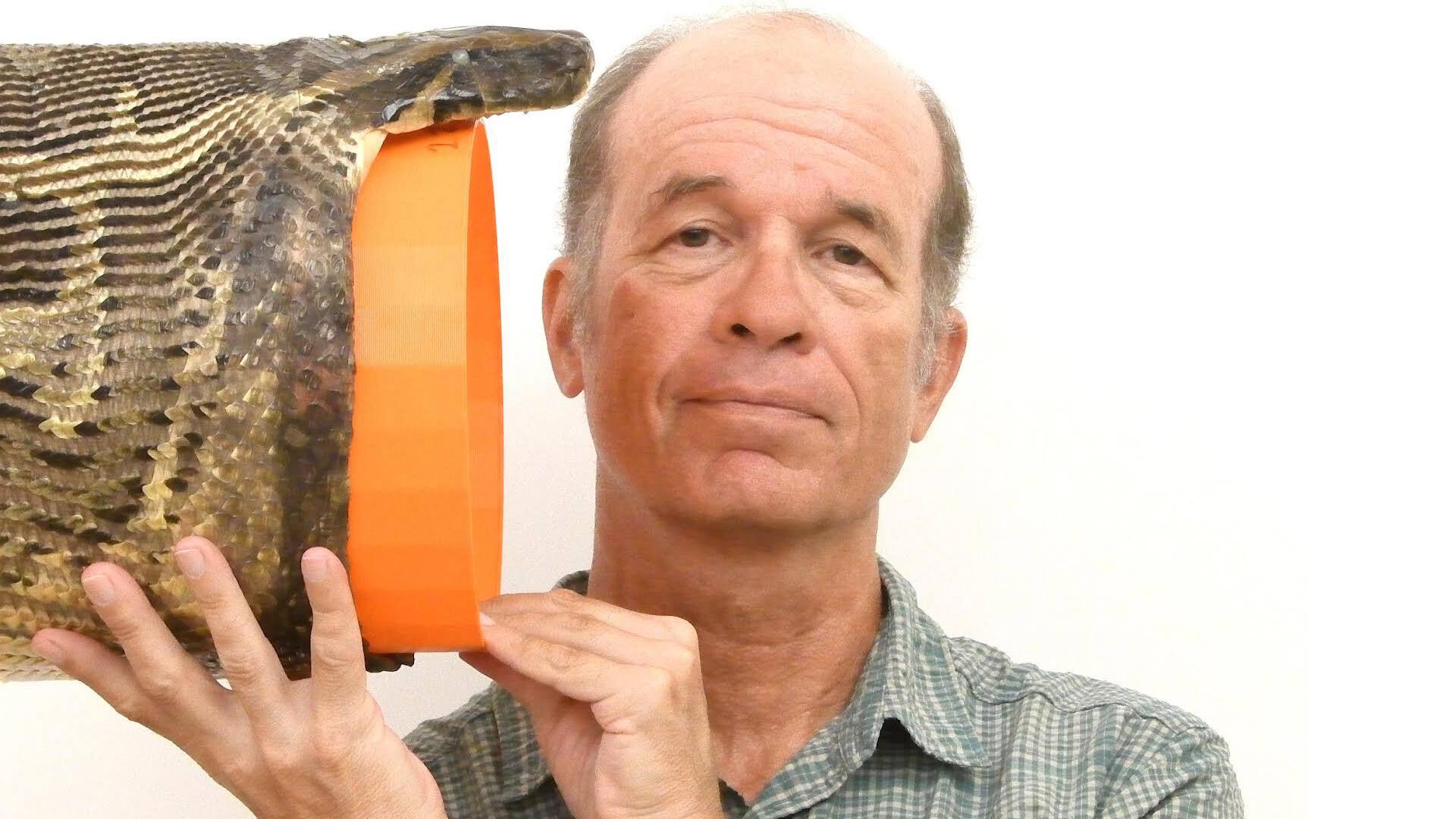

4. Jaw-dropping study details python's big gapes

Not much is off the menu for a hungry python, including white-tailed deer, alligators, impalas (even humans!). Pythons can easily devour prey much larger than they are. Biologists from the University of Cincinnati wanted to know how much these creatures could actually open their gapes in the name of a tasty snack while also better understanding how the snakes do it. The team discovered that the joints between pythons' jawbones are extremely flexible, enabling them to swallow pretty much anything.

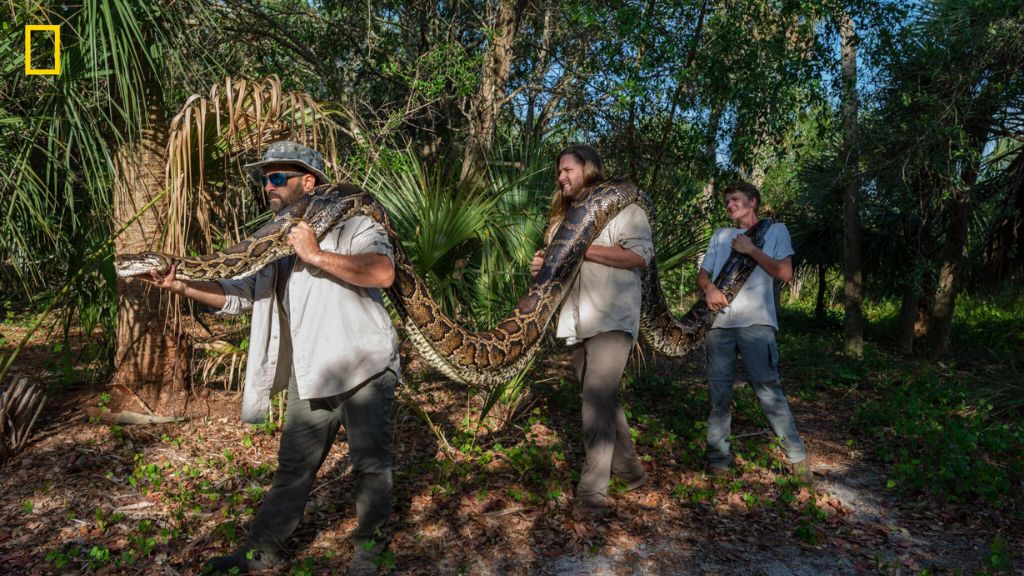

5. Jumbo Burmese python found in Florida

Using a smaller python as bait, researchers in the Everglades lured a massive female Burmese python (Python bivittatus) from its marshy habitat. The record-breaking reptile, which measured 18 feet (5.5 meters) long and weighed 215 pounds (98 kilograms), is the largest python ever recorded in the state. Most Burmese pythons are much smaller — 6 to 10 feet (2 to 3 m) long. Burmese pythons are considered invasive species in Florida.

6. How do snakes hiss?

Despite not having front teeth, snakes can make a telltale hissing sound. So, how do they do it? Unlike humans, who position their tongues against their front teeth to make an "ssss" sound, snakes use their glottis, a tiny opening at the bottom of their mouths that's connected to the trachea (windpipe) and their single lung. Every time the snake breathes, the glottis opens, releasing the spine-chilling sound.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

7. Snake cannibalism is real

A man in Georgia captured an incredibly gruesome sight on video: an eastern kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) swallowing a much larger timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus). While it's not entirely unheard of for snakes to eat their own kind, seeing a smaller snake dining on a larger one is a rarity. Because the victim was already far down the hatch, there's no knowing exactly how big it was, although the average timber rattlesnake is about 6 feet long, while eastern kingsnakes are a much shorter 4 feet (1.2 m).

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.