Shackled skeleton may be first direct evidence of slavery in Roman Britain

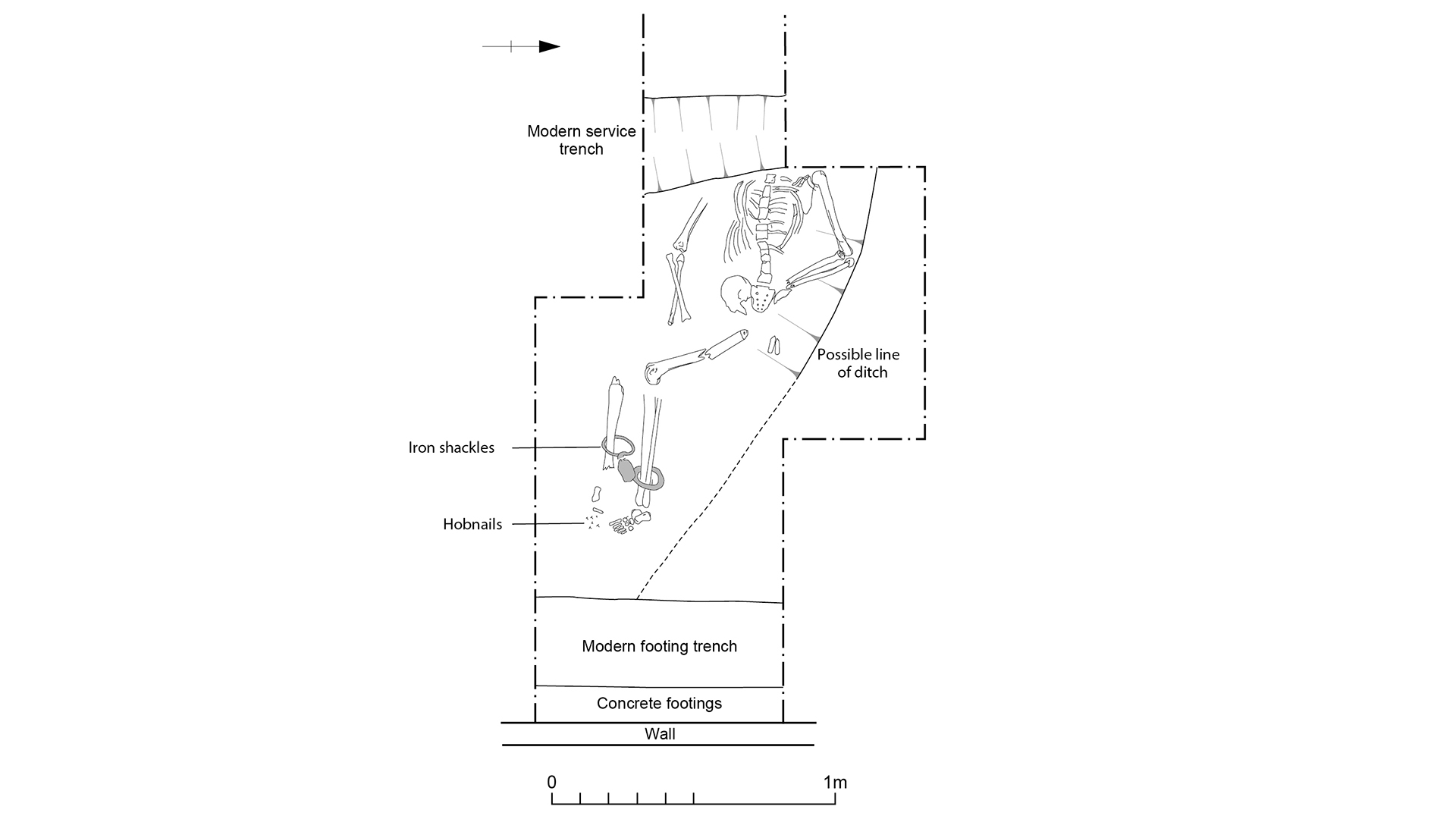

Iron fetters around the skeleton's ankles were secured in the center with a padlock.

A man who died in Roman Britain more than 1,500 years ago was buried wearing padlocked iron shackles securing his ankles, and his burial "is perhaps the best candidate" for the remains of an enslaved person in England when the land was under Roman control, scientists reported in a new study.

Construction workers discovered the headless skeleton in 2015 in Great Casterton, a village in England's East Midlands region. Archaeologists who recently analyzed the remains suspect that someone buried the man's corpse in shackles to demean him, and perhaps even to indicate that the man was enslaved.

While written records show that slavery was practiced throughout the Roman Empire, archaeologists have only rarely found direct evidence of enslavement, and this is the first burial from Roman-era Britain to include a skeleton still wearing iron ankle restraints. While it's impossible to tell if the man wore these shackles in life, whoever buried him in fetters did so to declare their dominance over the deceased, the study authors wrote.

Related: Photos: Major Roman settlement discovered in North Yorkshire

"For living wearers, shackles were both a form of imprisonment and a method of punishment, a source of discomfort, pain and stigma which may have left scars even after they had been removed," archaeologist and study co-author Michael Marshall, a senior prehistoric and Roman finds specialist at the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), said in a statement.

"However, the discovery of shackles in a burial suggests that they may have been used to exert power over dead bodies as well as the living, hinting that some of the symbolic consequences of imprisonment and slavery could extend even beyond death," he added.

The man was about 26 to 35 years old when he died, and the positioning of his bones and the shape of the burial pit suggested that he was placed in a pre-existing ditch — even though, at the time, there was a Roman cemetery less than 200 feet (60 meters) from the man's grave, researchers said in the study, which was published June 7 in the journal Britannia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Radiocarbon dating, a technique that measures the amount of radioactive carbon present in an object to determine its age, revealed that the remains dated from A.D. 226 to A.D. 427. The man had a bony spur on the left femur, which may have formed either after an injury healed or as a result of repetitive and demanding physical activity, according to the study.

Heavy iron fetters like the ones found on the Great Casterton skeleton "would have made moving quickly impossible, produced a slow uncomfortable shuffling gait and created a sound as the iron components moved against one another," the researchers reported. In Roman society, shackles such as these were "most commonly used to restrain and punish living slaves," lead study author Chris Chinnock, a human osteologist (an anatomist specializing in the study of bones) at MOLA, wrote in a blog post.

But why would the man have been buried while shackled, particularly since the restraints had a padlock and could have been removed? His burial, though unadorned and isolated, was deliberate, and his body was not simply abandoned after death, the study authors said. Rather, the placement of shackles on the corpse was likely a deliberate act by someone who had power over the dead man and who meant to incorporate a symbol of that power into the burial, the researchers suggested.

This burial offers a unique glimpse into the circumstances of a person who was denied escape from his shackles even in death. His remains highlight the presence of enslaved people in Roman Britain, and the discovery of his shackled skeleton should prompt archaeologists to dig deeper to find more long-hidden clues about slavery in the ancient world.

"That they [enslaved people] existed during the Roman period in Britain is unquestionable," Chinnock said in the statement. "Therefore, the questions we attempt to address from the archaeological remains can, and should, recognize the role slavery has played throughout history."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.