Stupendous sharks: The largest, smallest and strangest sharks in the world

Sharks come in a remarkable array of shapes and sizes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Introduction

It's Shark Week: Time to celebrate all that is toothy, finned, and leather-skinned. The Discovery Channel's annual week of shark programming starts July 24 — you can sink your teeth into all the sharky goodness with our Shark Week streaming guide. In honor of these incredible creatures, we've rounded up a list of shark superlatives. Which of these cartilaginous wonders is the biggest shark, the fastest, the weirdest? We've got your answers right here.

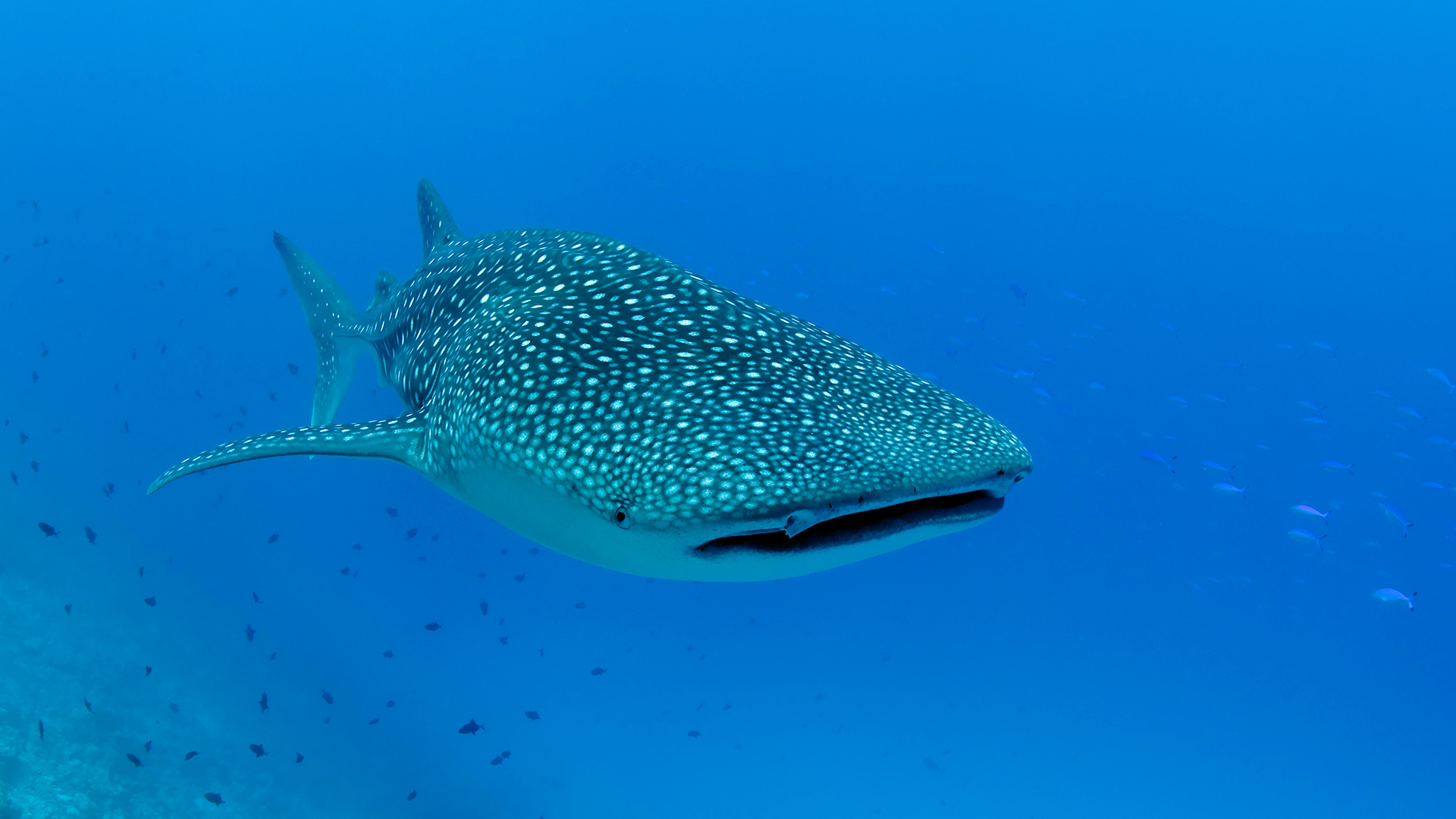

The biggest shark

The largest shark alive today is a gentle giant: the whale shark. These filter-feeders typically grow to be about 40 feet long (12.1 meters) and weigh around 11 tons (9,979 kilograms), according to the World Wildlife Fund. And they do it on a diet of plankton.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide. They give birth to live young, but scientists know almost nothing about their mating rituals or birthing behaviors (though researchers did, in 2018, conduct ultrasounds on female whale sharks near the Galapagos Islands, the Guardian reported). Scientists also don't know why these sharks sometimes make incredible dives as deep as 6,000 feet (1,800 m), a behavior that scientists have only started to track within the last decade.

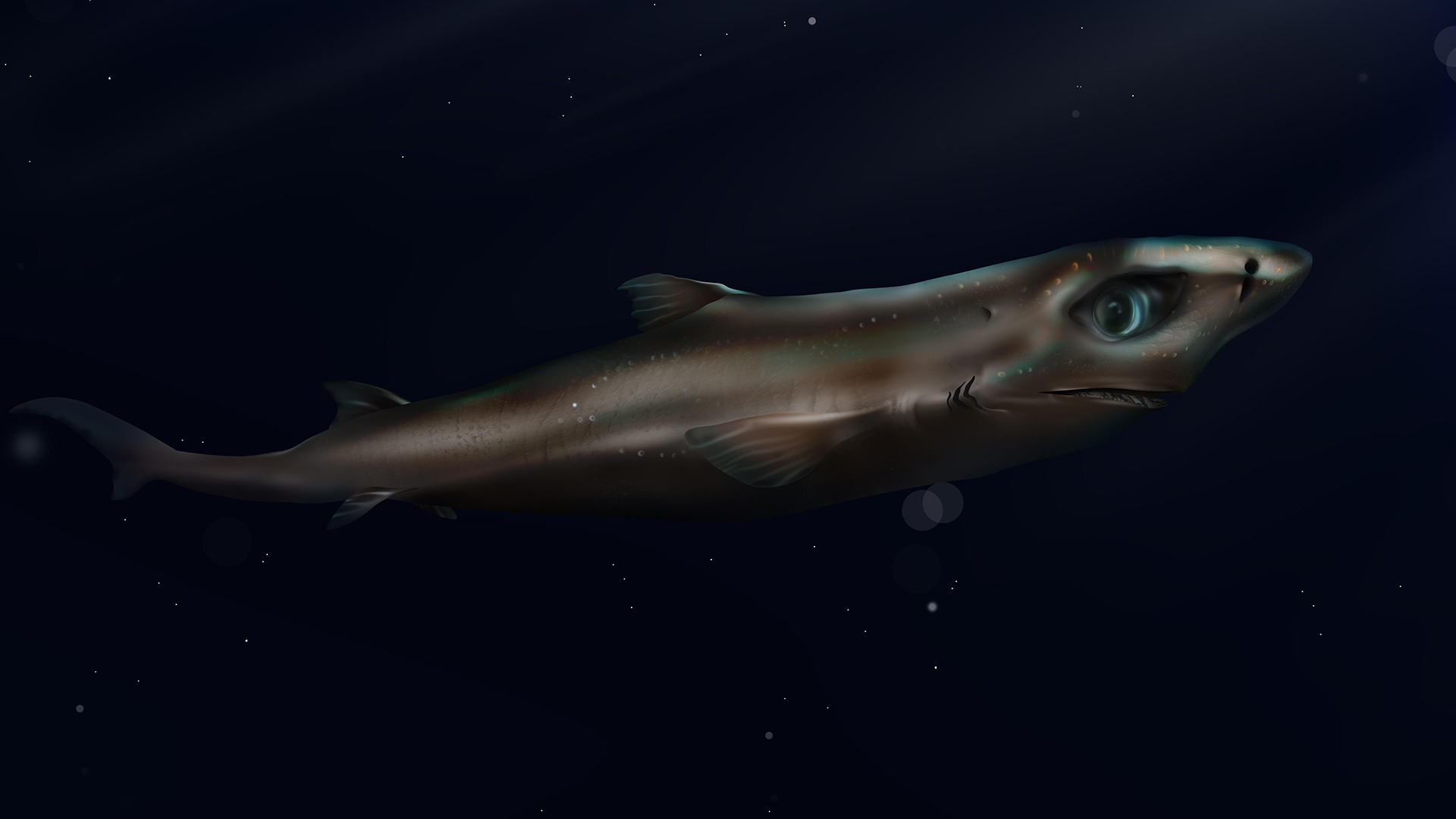

The smallest shark

On the other end of the size spectrum sits the dwarf lanternshark (Etmopterus perryi). This diminutive deep-sea dweller grows to be only about 7.9 inches (20 centimeters) long. It's rarely observed, given that it swims at depths between 928 and 1,440 feet (283 and 439 m) below the sea surface, according to the Smithsonian Institution . So far, the shark has only been seen in the waters off Colombia and Venezuela.

The dwarf lanternshark has a belly lined with photophores — light-emitting organs that help the shark stay camouflaged. In shallower water, the gentle glow blends in with sunlight filtering down from the ocean surface, according to Smithsonian, while the lights help attract prey when the shark trolls deeper waters.

Lanternsharks are an odd group. A relative of the dwarf lanternshark, the viper dogfish (Trigonognathus kabeyai), not only has a light-up belly but also sports toothy, goblin-like jaws.

The fastest shark

The shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) is the fastest known shark. This streamlined shark can swim at 31 mph (50 km/h) and pour on the speed for short bursts of up to 46 mph (74 km/h), according to the Smithsonian. Makos are apex predators who use their speed to hunt bony fish. They're also expert jumpers, regularly leaping at least 10 feet (3 m) out of the water. The sharks are sometimes caught by deep-sea anglers and may jump into fishing boats in an attempt to shake free of the anglers' hooks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Makos can grow to be up to 13 feet (4 m) long and are found in temperate and tropical oceans around the globe. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the mako as endangered, in part due to overfishing.

The longest-lived shark

The longest-lived shark also happens to be the record holder for longest-living vertebrate. Greenland sharks have long been known to have extreme lifespans, but 2016 research that dated the layers in the sharks' eye lenses found that the sharks were between 272 and 512 years old. Despite the uncertainty in the estimate, even the lower number clinches the shark's trophy for longevity in animal species with backbones.

Greenland sharks are the only sharks that can survive the cold of the Arctic Ocean all year, according to the National Ocean Service. They have extremely slow metabolisms and grow only about a centimeter a year — but when you live long enough, all those centimeters add up. Over their long lives, these sharks can grow to be 19.7 feet (6 m) from nose to tail.

The farthest-migrating shark

The whale shark is an overachiever. Not only does it hold the record for largest shark, this peaceful creature also takes home the trophy for farthest migration. In 2018, researchers reported in the journal Marine Biodiversity Records that they'd tagged a female whale shark in Panama. Eight hundred and forty-one days later, she showed up near the Marianas Trench, a journey of 12,515.7 miles (20,142 kilometers).

It was the longest recorded whale shark journey ever, but the study authors argued that other tracking data suggests that long journeys aren't unusual for whale sharks. For example, the researchers wrote, whale sharks near the Galapagos have been clocked traveling 41.6 miles (67 km) a day, and other whale sharks with tags have been tracked across thousands of miles.

The deepest-living shark

Sharks are found from the surface of the ocean to the deep sea. The lowest-living shark discovered so far is the Portuguese dogfish (Centroscymnus coelolepis), a relatively small shark that grows to about 3 feet (0.94 m) in length. These sharks are benthic, meaning they live on the ocean floor, and they have been found as deep as 12,057 feet (3,675 m), according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Portuguese dogfish are typically black or dark brown and possess approximately 98 teeth, which these deep-sea hunters use to snag fish and cephalopods.

The most bizarre shark

It should be clear by now that sharks are a pretty diverse group. And, as in any family, among their number they count some real oddballs. There's the "pig fish," or angular roughshark (Oxynotus centrina), which snorts like a hog when pulled from the water. There's the pocket shark (Mollisquama mississippiensis), which is shaped like a tiny sperm whale. There are wobbegong sharks (family Orectolobidae), which look like shag rugs thanks to their mottled camouflage and ragged sensory organs.

But for our money, the weirdest shark in the sea has got to be the frilled shark. These elusive living fossils haven't changed much for 80 million years. They have long, eel-like bodies that can grow to about 6 feet (1.8 m) long, and they've been trolling the deep seas, snagging prey with their 300 prong-pointed teeth, since before the dinosaurs died out. Because they live so deep, frilled sharks are rarely seen, according to the Ocean Conservancy. Given their rows of backward teeth and ominous, club-like heads, maybe that's a good thing.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus