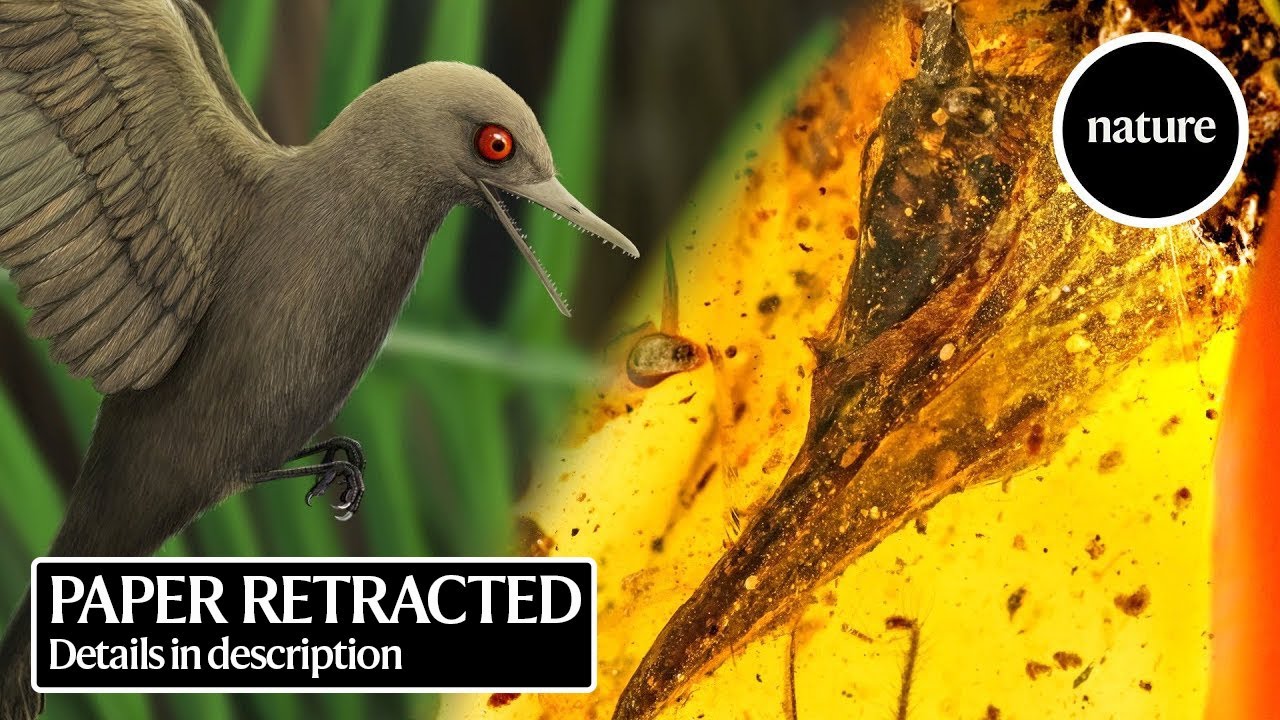

Trapped in amber, this could be the smallest dinosaur ever found

This tiny weirdo had about 100 sharp teeth and lizard-like eyes.

Editor's Note: This study was retracted on July 22, 2020. New evidence indicates that this creature may actually be a lizard, not a bird-like dinosaur. To read Live Science's full coverage of the retraction, go here.

About 99 million years ago, a "super weird" and incredibly small bird-like dinosaur got stuck in a gob of tree resin that eventually hardened into amber, preserving what may be the tiniest dinosaur ever known to live on Earth, researchers of a new study said.

This dinosaur, dubbed Oculudentavis khaungraae, was so slight, it likely weighed just 0.07 ounces (2 grams), the weight of two dollar bills. Despite its size, this little beast probably wasn't timid; it had roughly 100 teeth, and they were sharp.

"It has more teeth than any other Mesozoic [dinosaur-age] bird that we know of," said study co-lead researcher Jingmai O'Connor, a senior professor of vertebrate paleontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It even had teeth in the back of its jaw, under its eye, she said, "which suggests that the animal could really open its mouth really, really wide."

Related: Photos: Hatchling preserved in amber

But really wide for such a pipsqueak probably just allowed the predator to feed on small meals. "Since it's so tiny, we envision the only thing it was possibly able to feed on was insects," and other invertebrates, O'Connor told Live Science.

The amber chunk contains just the dinosaur's head, and even that was imperiled over the ages. Tiny tunnels in the specimen indicate that bivalves bored into the amber and damaged part of the dinosaur's skull.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Luckily, other parts of the skull are more intact. Researchers marveled at its unique anatomy after using specialized scans to analyze the specimen. Rather than distinct sockets for its teeth, "the teeth are fused into the skull, which is highly unusual for a dinosaur, including birds," O'Connor said. (A quick note: Birds evolved from dinosaurs, which explains why, in part, early birds had teeth.)

"A lot of the oddities of this specimen we simply explain through the process of miniaturization," O'Connor said, which goes back to where the dinosaur was found, and where it lived during the Cretaceous period, the last period of the dinosaur age.

Miniature dinosaur

The pebble-size amber piece was dug up in 2016 from a mine in Myanmar (formerly Burma), and purchased by Khaung Ra, who donated it to her son-in-law's museum, the Hupoge Amber Museum in China. (The same museum that has a wee Cretaceous-age chick preserved in amber.) Then, study co-lead researcher Lida Xing, an associate professor at the China University of Geosciences, showed O'Connor scans of the bird-like dinosaur. Her reaction?

"Whoa."

O'Connor and her colleagues named the dinosaur Oculudentavis khaungraae, combining the Latin words "oculus" (eye), "dentes" (teeth) and "aves" (bird). The species name honors Khaung Ra for donating the specimen.

During the dinosaur's lifetime, it flew around resin-producing trees growing in brackish waters at a time when that part of Myanmar was on an island arc. A theory on animal size suggests that larger creatures "miniaturize" when they evolve on isolated islands, like this one.

It appears that living on an island environment led O. khaungraae to develop some odd anatomical features. For instance, the bones around its eyes form a spoon-shape, just like a lizard, "which is weird," O'Connor said. Moreover, the eyes may have rested on a cup-shaped bone, making them bulge outward, she said.

Related: Photos: Dinosaur-era bird sported ribbon-like feathers

The inner diameter of the eye socket indicates that the toothy dinosaur had small pupils, a clue that it hunted during the day, when there was sunlight. But, unlike other predators, its eyes are on the sides of its head, meaning it had little or no binocular vision, a feature that likely made it challenging to hunt.

The smallest dinosaur?

The current record-holder for the "smallest dinosaur" is actually a bird, the bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae). Because specimens are hard to come by, O'Connor and her colleagues couldn't measure one to get exact dimensions. Even so, after measuring the vervain hummingbird (Mellisuga minima) — which is a tad larger than the bee hummingbird — they found their dinosaur was smaller.

In addition, O. khaungraae was the smallest dinosaur of its time. It's just one-sixth the size of the smallest known early fossil bird, making it the smallest known dinosaur of the Mesozoic era (252 million to 66 million years ago), Roger Benson, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Oxford, wrote in an accompanying opinion piece in the journal Nature.

Of note, even though the head is preserved in amber, O'Connor noted that a "Jurassic Park" situation is unlikely. While fragments of the dinosaur's DNA may still exist in the specimen, there isn't nearly enough for cloning purposes, she said.

"It's not going to happen," she said, adding, "Have you seen "Jurassic Park"? It does not end well. Why would we want to do that?"

Astonishing find

The little dinosaur find has led to outsize reactions from other paleontologists.

The discovery is "truly astonishing," said Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of dinosaur paleobiology at the University of Calgary, who was not involved in the study.

"This discovery is a stark reminder that ancient birds, and even non-bird dinosaurs potentially, may have evolved to diminutive sizes, but are unknown because they are too small to preserve in the fossil record under ordinary circumstances," Zelenitsky told Live Science.

O. khaungraae "provides a fascinating look at miniaturization in an early bird," said Sara Burch, an assistant professor of biology who specializes in birds and meat-eating theropod dinosaurs at the State University of New York College at Geneseo, who wasn't involved with the study.

"This new specimen is the size of a hummingbird, but exhibits some unique and unexpected adaptations that suggest that it was quite different ecologically," Burch told Live Science in an email. "Specimens like this give us the opportunity to learn more about what is biologically possible at very small body sizes."

The study was published online today (March 11) in the journal Nature.

- Images: These downy dinosaurs sported feathers

- Avian ancestors: Dinosaurs that learned to fly

- Photos: Velociraptor cousin had short arms and feathery plumage

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.