Could a powerful solar storm wipe out the internet?

Space weather has been known to cause power outages and disrupt satellite function.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In Becky Chambers' 2019 novella "To Be Taught, If Fortunate," a massive solar storm wipes out Earth's internet, leaving a group of astronauts stranded in space with no way to phone home. It's a terrifying prospect, but could a solar storm knock out the internet in real life? And if so, how likely is that to happen?

Yes, it could happen, but it would take a giant solar storm, Mathew Owens, a solar physicist at the University of Reading in the U.K., told Live Science. "You would really need some huge event to do that, which is not impossible," Owens said. "But I would think that knocking out power grids is more likely." In fact, this phenomenon has already happened on a small scale.

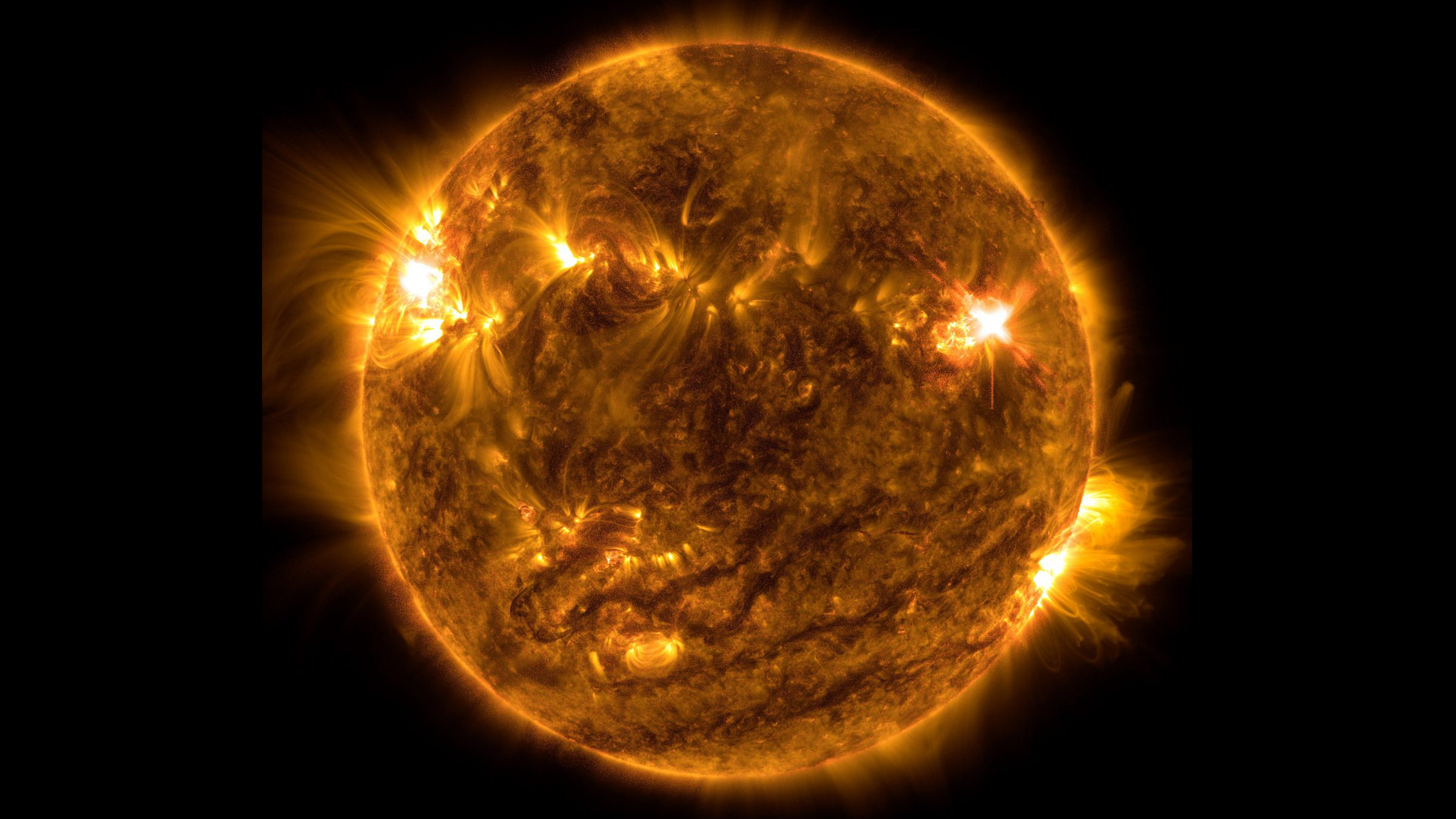

Solar storms, also known as space weather, occur when the sun releases an intense burst of electromagnetic radiation. This disturbance throws off waves of energy that travel outward, impacting other bodies in the solar system, including Earth. When the wayward electromagnetic waves interact with Earth's own magnetic field, they have a couple of effects.

Related: What's the maximum number of planets that could orbit the sun?

The first is that they cause electric currents to flow in Earth's upper atmosphere, heating the air "just like how your electric blanket works," Owens said. These geomagnetic storms can create beautiful auroras to appear over polar regions, but they can also disrupt radio signals and GPS. What's more, as the atmosphere heats, it puffs up like a marshmallow, adding extra drag to satellites in low Earth orbit and knocking smaller pieces of space junk off course.

Space weather's other impact is more terrestrial. As powerful electric currents flow through our planet's upper atmosphere, they induce powerful currents that flow through the crust as well. This can interfere with electrical conductors sitting on top of the crust, such as power grids — the network of transmission lines that carry electricity from generating stations to homes and buildings. The result is localized power outages that can be difficult to fix; one such event struck Quebec on March 13, 1989, resulting in a 12-hour blackout, according to NASA. More recently, a solar flare knocked out 40 Starlink satellites when SpaceX failed to check the space weather forecast, Live Science previously reported.

Luckily, taking out a few Starlink satellites isn't enough to mess up global internet access. In order to take down the internet entirely, a solar storm would need to interfere with the ultra-long fiber optic cables that stretch beneath the oceans and link continents. Every 30 to 90 miles (50 to 145 kilometers), these cables are equipped with repeaters that help boost their signal as it travels. While the cables themselves aren't vulnerable to geomagnetic storms, the repeaters are. And if one repeater goes out, it could be enough to take down the entire cable, and if enough cables went offline, it could cause an "internet apocalypse," Live Science previously reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A global internet blackout would be potentially catastrophic — it would disrupt everything from the supply chain to the medical system to the stock market to individual people's basic ability to work and communicate.

There are a few ways to protect the internet against the next mega solar storm. The first is to shore up power grids, satellites and undersea cables against being overloaded by the influx of current, including failsafes to strategically shut off grids during the solar storm surge.

The second, less expensive way is to work out a better method of predicting solar storms in the long term.

Can we predict solar storms?

Solar storms are also notoriously tricky to predict. In part, they can be "very difficult to pin down," Owens said. "Because while space weather has been going on for thousands of years, the technology that is affected by it has only been around for a few decades."

Current technology can predict solar storms up to two days before they strike Earth based on the activity of sunspots, black patches on the sun's surface that indicate areas of high plasma activity. But scientists cannot track solar storms the way they follow hurricanes. Instead, they turn to other clues, such as where the sun is in its current solar cycle. NASA and the European Space Agency are currently researching ways to make such forecasts using a combination of historical data and more recent observations.

The sun goes through approximately 11-year cycles of higher or lower activity, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NASA previously predicted that the sun's next peak of activity, known as the solar maximum, should hit around 2025. However, recent observations of sunspots and solar weather indicate that the next solar maximum will come much sooner, and hit much harder, the NASA's estimates. The upcoming peak, which could begin as soon as late 2023, will likely be more severe than the last few solar maximums, which were relatively mild.

"The sun has been fairly quiet since the 90s," said Owens. The last worldwide geomagnetic storm (at least on record) is the so-called "Carrington Event" of 1859, during which auroras were observed as far south as Cuba and Honolulu, Hawaii. Had the internet existed during this event, there's a chance it would have been seriously disrupted.

Hopefully, scientists will be able to find a way to predict or minimize the impact of the next Carrington Event before we find ourselves in an internet-less future… although, considering the terrible depths of social media, maybe there are worse fates.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus