Small NASA rocket will study boundary of interstellar space

For a few brief minutes, a suborbital rocket from NASA has an ambitious plan to seek out particles from interstellar space.

A mission called Spatial Heterodyne Interferometric Emission Line Dynamics Spectrometer (SHIELDS) will lift off from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico no earlier than Monday (April 19). It will soar to a peak height of 186 miles (roughly 300 kilometers) — a little more than half the altitude of the International Space Station — and peer at the sky for a few minutes with its telescope.

With this capability, it is possible to see light from particles from beyond our solar system even on a short flight outside the Earth's atmosphere. The mission follows a similar study in 2014; this mission will extend the project's scope.

Related: These NASA rocket launches to study Earth's atmosphere are just gorgeous (photos)

To understand what SHIELDS is looking for, it's best to start with a quick overview of our solar system structure and nearby regions. The planets, asteroids, gas, dust and everything else in our neighborhood is situated in a cluster of gas clouds, called the Local Bubble. The bubble is roughly 300 light-years long and encompasses hundreds of stars, including our own sun.

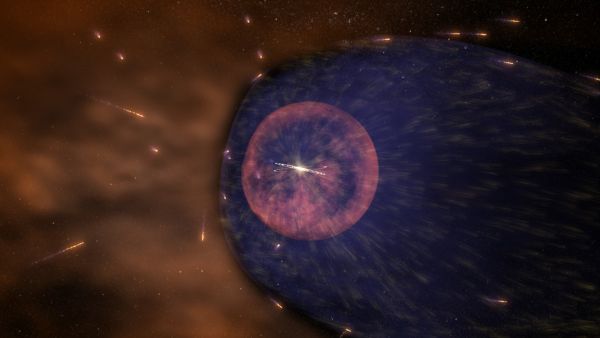

Inside this structure, our solar system is encased in a magnetic bubble created by the sun that's known as the heliosphere. As the heliosphere moves through the Local Bubble at roughly 52,000 mph (84,000 km/h), particles from interstellar space fall on the heliosphere "like rain against a windshield," NASA said in a release.

"Our heliosphere is more like a rubber raft than a wooden sailboat: its surroundings mold its shape," NASA continued in the release. "Exactly how and where our heliosphere's lining deforms gives us clues about the nature of the interstellar space outside it."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

SHIELDS will examine light from hydrogen atoms that originated in interstellar space. These atoms have equal balances of fundamental particles called protons (positive charge) and electrons (negative charge). Since the positive and negative charges balance each other out, the interstellar hydrogen atoms have a neutral electrical charge, which allows them to cross magnetic field lines.

The mission will look at what happens to the trajectories of the atoms as they creep into the heliopause. "Charged particles flow around the heliopause, forming a barrier, [but] neutral particles from interstellar space must pass through this gauntlet, which alters their paths," NASA noted.

SHIELDS will seek out the light from these hydrogen atoms and measure how far the wavelength stretches or contracts, which indicates how the particles are moving through space. This information will allow investigators to figure out the shape and matter density around the heliopause barrier — giving some more clues about interstellar space and the clouds within it.

"There's a lot of uncertainty about the fine structure of the interstellar medium — our maps are kind of crude," Walt Harris, principal investigator for SHIELDS and a solar and heliospheric researcher at the University of Arizona, said in the same NASA release. "We know the general outlines of these clouds, but we don't know what's happening inside them."

SHIELDS will likely also give scientists insights about the galaxy's magnetic field, and perhaps allow astronomers to make some predictions about where our solar system will be in the far future. Scientists project that our neighborhood will move out of the Local Bubble in 50,000 years based on its current speed and trajectory, but to where is poorly understood. (It's far from the first time Earth, the planets and nearby stars have done this, but we haven't been able to document the phenomenon in real-time before.)

The local observations SHIELDS gathers will augment some data from interstellar space itself. The twin Voyager spacecraft, which launched in 1977, continue to send back observations about their journey through interstellar space. In December, for example, the mission spotted a newly found kind of electron burst that could give more insights into flaring stars.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.