8 stunning James Webb Space Telescope discoveries made in 2023

The oldest ever black holes, a preview of our solar system's gory demise, and a measurement of distant starlight that threatens to bring the standard of cosmology crashing down — here are the JWST's wildest discoveries of 2023.

Dec. 25 is a pretty special birthday for many around the world, but it's also a big deal for fans of astronomy — who will be celebrating the second anniversary of the launch of NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Since coming online in mid-2022, the most powerful telescope ever built has both blown our minds with its stunning images and swept away many of our preconceptions about the early universe.

From inexplicably bright galaxies to life on alien planets, and even the potential demise of our standard model of the universe, here are the JWST's biggest findings of 2023.

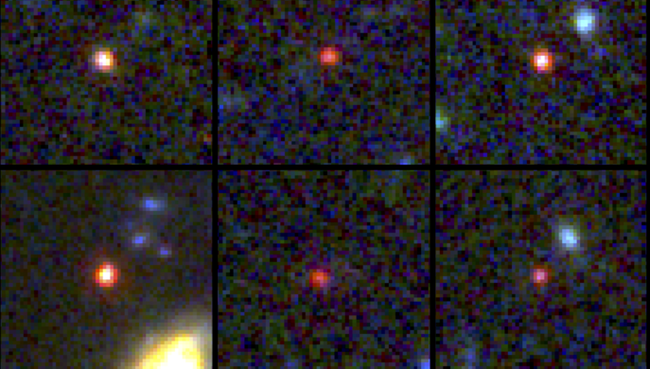

Spotting six 'impossible' galaxies at the dawn of time

Not long after coming online, the JWST immediately discovered six enormous "universe breaker" galaxies, containing what seemed to be almost as many stars as the Milky Way, dating to just 500 million years after the Big Bang.

The finding caused a stir in the astronomical world, with some scientists suggesting that it had put our current view of galaxy evolution, or even our understanding of the universe, into doubt.

Related: James Webb telescope finds 'vanishing' galaxy from the dawn of the universe

The strange discovery pointed to a deepening mystery around how large galaxies first bloomed in our universe. After running simulations, other astronomers suggested that the galaxies might not contain as many stars as first seemed, and could instead just be glowing unusually brightly. Whatever the answer, follow-up observations of the mysterious galaxies are in order before scientists can be certain.

Casting doubt on the standard model of cosmology

Besides throwing out seeds of potential new crises in astronomy, the telescope also cemented an old one: the Hubble tension.

Put simply, the universe is expanding, but depending on where cosmologists look, it's doing so at different rates. In the past, the two best experiments to measure the expansion rate were the European Space Agency's Planck satellite (which gave a most likely expansion rate of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec) and the Hubble Space telescope, which studied pulsating stars called Cepheids and found a higher value of 73 km/s/Mpc.

Cosmologists thought this tension might be down to uncertainty caused by Hubble not distinguishing between Cepheids and background stars, but the JWST snuffed out that hope with a result of 74 km/s/Mpc.

Since then, cosmology has lurched deeper into a "crisis" that could reveal new physics or even break the standard model. What might resolve it? More measurements by the JWST, of course.

Related: After 2 years, the James Webb telescope has broken cosmology. Can it be fixed?

Finding the oldest black hole in the universe — twice

There weren't just inexplicably large ancient galaxies on the JWST's list of discoveries this year, but whopping black holes too. The first, CEERS 1019, had a mass 10 million times that of our sun and was found by the JWST just 570 million years after the Big Bang — making it the oldest black hole ever spotted at the time of its discovery in April 2023.

We say "at the time" because the JWST didn't rest on its laurels. Earlier this month, the telescope discovered an even older massive black hole 440 million years after the universe began.

How these gigantic space-time ruptures swelled to such staggering scales so early on is an ongoing mystery. Astrophysicists are currently exploring options that include the black holes being formed from the rapid collapse of giant gas clouds, although they haven't ruled out that some may have been seeded by hypothesized "primordial" black holes, thought to be created moments after — and in some theories even before — the universe began.

Spotting dozens of rogue objects floating through space in pairs

The telescope's ultrapowerful eye has also revealed glimpses of completely new, unexplainable objects. After being trained on the Orion Nebula, the JWST found 42 pairs of Jupiter-mass binary objects, or "JuMBOs" — Jupiter-sized planets drifting through space in pairs, some as far apart from each other as 390 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

Related: James Webb telescope finds universe's smallest 'failed star' in cluster full of mystery molecules

The JuMBOs are too small to be stars, but as they bafflingly exist in pairs, they are unlikely to be rogue planets ejected from solar systems. Their discovery has alerted astronomers to a brand-new formation mechanism for planets or even for failed stars.

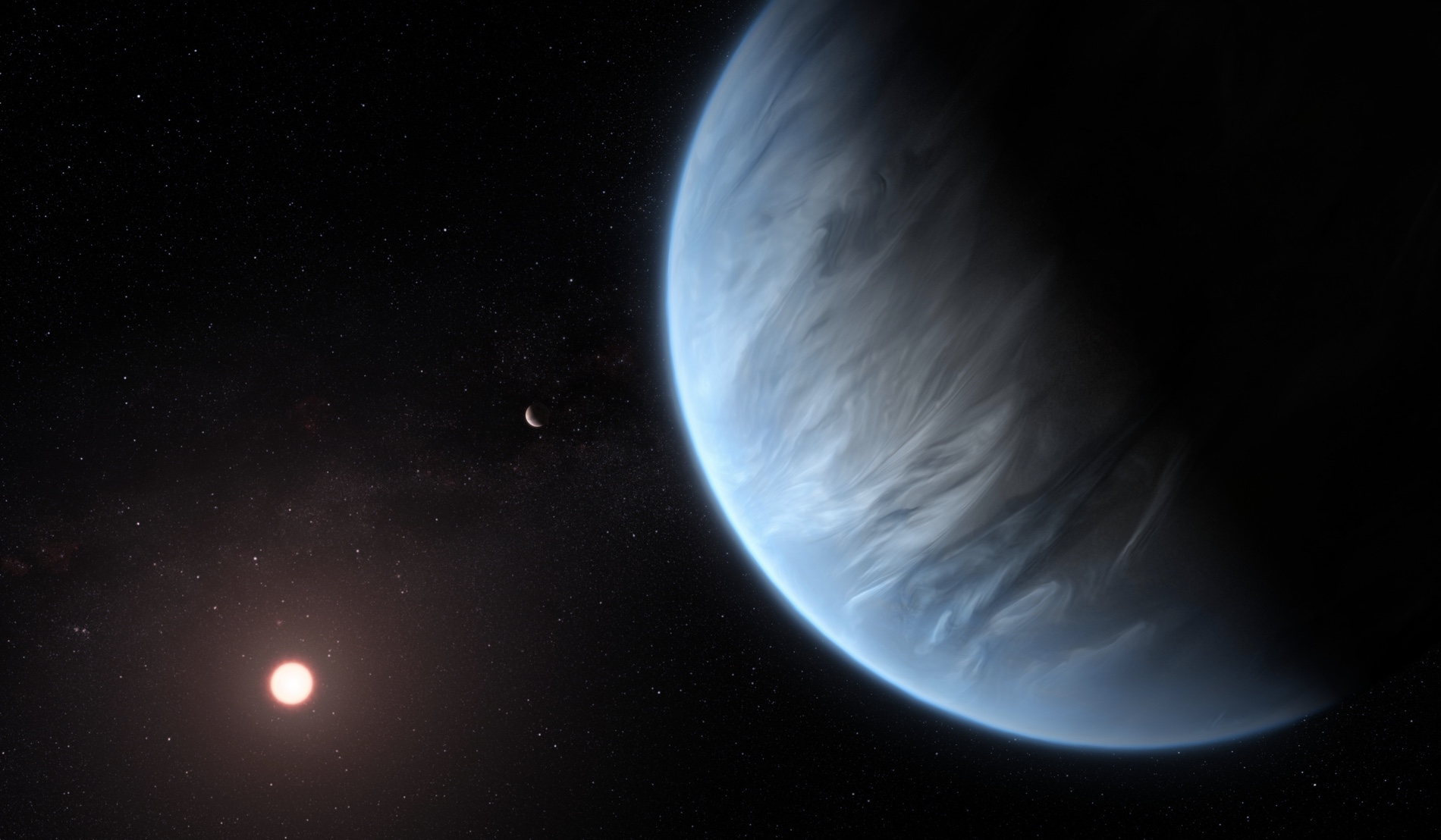

Spying potential signs of alien life on a distant watery world

Another feature of the JWST is its ability to measure a spectrum of the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, a toolkit which enabled it to spot the potential signs of life in "alien farts" on a Goldilocks water world 120 light-years away.

The exoplanet it found, K2-18 b, is a sub-Neptune planet (weighing in somewhere between the mass of Earth and Neptune) orbiting the habitable zone of a red dwarf star. After taking an atmospheric spectrum, the JWST found it rich with hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide — all chemical markers of a hydrogen-rich hycean world that is a prime contender for extraterrestrial life.

More tantalizing still was the detection of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a cabbage-smelling compound only known to be produced by microscopic algae in Earth's oceans. The researchers want to take more peeks at K2-18 b and worlds like it to find further evidence for extraterrestrial life beyond our planet.

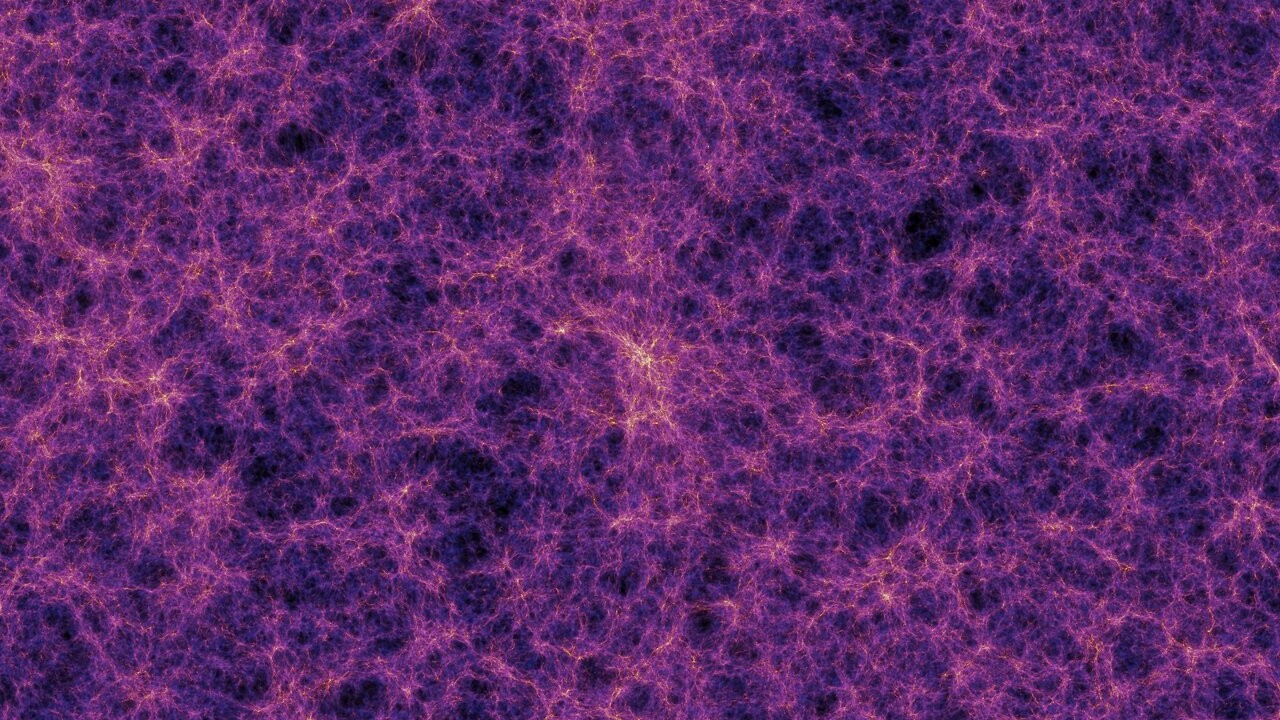

Finding the oldest strand in the 'cosmic web' ever seen

Stars and galaxies aren't evenly spread throughout our universe. Instead, they're connected by an enormous cosmic web — a gigantic network of crisscrossing celestial superhighways paved with hydrogen gas and dark matter.

Taking shape in the chaotic aftermath of the Big Bang, the web's tendrils formed as clumps from the roiling broth of the young universe; where multiple strands of the web intersected, galaxies eventually formed.

Insights into the structure of this web not only give us a glimpse of the chaotic particle interactions that led to a universe existing in the first place, so astronomers using the JWST were stunned when they spotted the earliest strand of this web ever seen — a gassy tendril made of of 10 closely packed galaxies spanning more than 3 million light-years in length.

The filament formed when the universe was just 830 million years old, and is partially wrapped around a bright black hole. By finding more, researchers hope to find answers as to how the very first galaxies formed.

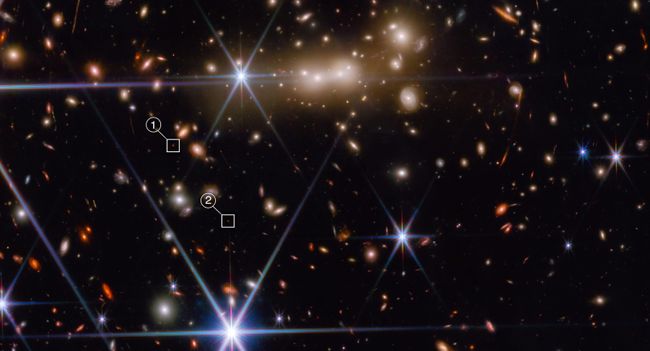

Snapping an eerily perfect 'Einstein ring', the most distant gravitationally lensed object ever seen

Another addition to the JWST's long list of cosmic distance records this year was its discovery of the most distant gravitationally lensed object ever seen — an "Einstein ring" produced by the warping of light from a distant galaxy around a mysteriously dense foreground galaxy.

How distant? A mind-bending 21 billion light years away, which, given the universe's 13.8 billion years of age, means that the light from the galaxy traveled almost twice that distance due to the cosmos's expansion.

Besides making for a very pretty picture, distantly-lensed light shows like this could help astronomers to understand the puzzling nature of dark matter: the unseen substance believed to make up 70% of the universe's matter.

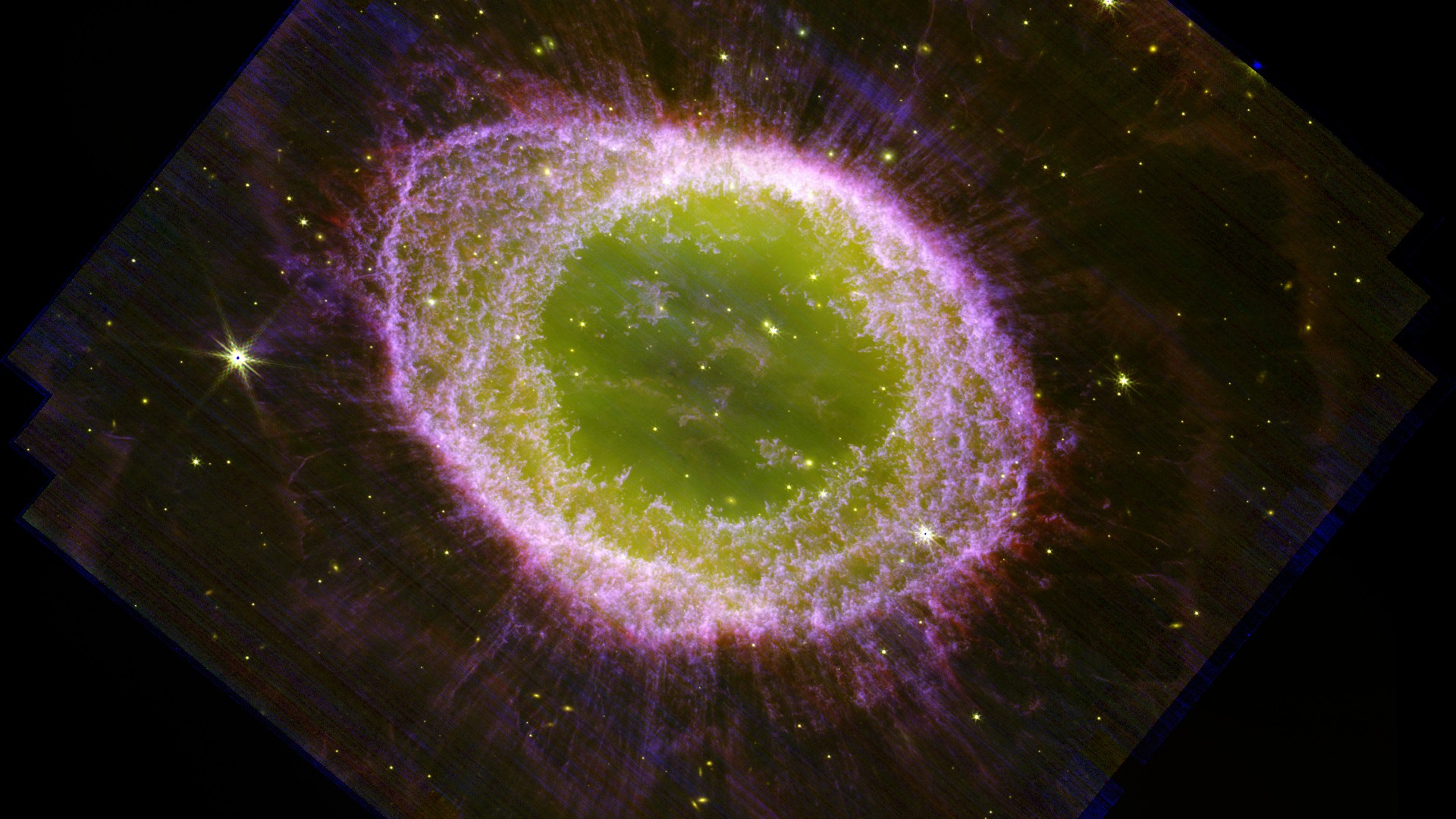

Zooming in on a gory 'preview' of the sun's distant future

James Webb has mostly revealed insight into how everything began, but what about our eventual demise? Fear not (or maybe fear away), doom-mongers: The JWST had you covered this year with a spectacular light show from a dying star, a preview into the demise of our solar system.

The donut-shaped Ring Nebula, also known as Messier 57 (M57), is a 2,200 light-years distant corpse of an exploded star, harboring at its center a tiny pinprick of a white dwarf that is the last remaining piece of the star's core.

As it reached the end of its life, the star exploded outwards, hurling its innards far and wide to form what looks like a gigantic eye. The explosion likely obliterated or ejected any unfortunate planets in its way — a fate that will similarly befall our own solar system in 5 billion years time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.