Are there any planets in the universe that aren't round?

Earth is round, but are there any planets in the universe that aren't?

Every planet in our solar system is essentially round. But out in the universe, are there any planets that aren't spherical?

Technically, planets are round, by definition; they need to have enough mass to produce the gravity required to pull themselves into a spherical shape.

"Actually, one of the specifications for being a planet is, they have enough mass that makes them round," Susana Barros, a senior researcher at the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences in Portugal, told Live Science.

But that doesn't necessarily mean planets are perfect spheres. "We call them round, but they're not really perfectly round, including our own Earth," Amirhossein Bagheri, a planetary science and geophysics researcher at the California Institute of Technology, told Live Science.

Earth and planets like it often have a bulge around the equator caused by centrifugal force, the outward force experienced by an object that's spinning. On Earth, the bulge is slight but significant: Due to differences in centrifugal force and the distance from Earth's center, things weigh about 0.5% less at the equator than they do at the poles.

Related: How many galaxies are in the universe?

But this effect can be dramatic in the right circumstances. "If the planet is rotating very fast, the poles will flatten," Barros said, leading to a squished, football-like shape.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Centrifugal force isn't the only force that can alter the shape of a planet. "If the body is close enough to the host star, then these gravitational forces that are acting on the body become so large that the planet gets elongated," Bagheri said.

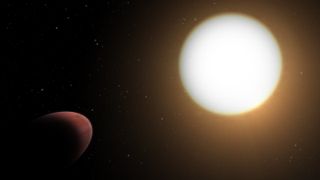

One such body is the exoplanet WASP-103 b, a gas giant twice the size of Jupiter and 1.5 times its mass that orbits a star nearly twice as large as the sun.

WASP-103 b is also "really, really close to the star," Barros said. That changes its shape. "There's a balance between the force of the gas that's called the hydrostatic equilibrium, that wants to expand the planet … and the strength of the gravitational attraction." This pull from the host star leads to a planet that's "tear-shaped," Barros said.

This deformation can even change the way the planet rotates. If a planet starts out with a pronounced bulge toward the home star and continues rotating normally, "then this bulge would not always be in the same place," Barros said.

Moving that bulge around the planet as it rotates uses a lot of energy. "So they start like this, but then, very fast, they will align," Barros said. The planet becomes tidally locked to its host star, with the same side of the planet facing the star at all times.

On top of that, WASP-103 b is orbiting its star extremely quickly, leading to a flattening of its poles, Barros said. The result is a very squished planet.

But even a squished sphere is still mostly spherical. Some scientists have posed the possibility of a toroidal — or doughnut-shaped — planet. This could hypothetically happen if a planet were rotating fast enough for the outward centrifugal force to outweigh the force of gravity pulling the planet's mass toward its center.

But a toroidal planet has never been observed, and it's not likely to be in the near future. "It's more science fiction than science," Bagheri said.

Ashley Hamer is a contributing writer for Live Science who has written about everything from space and quantum physics to health and psychology. She's the host of the podcast Taboo Science and the former host of Curiosity Daily from Discovery. She has also written for the YouTube channels SciShow and It's Okay to Be Smart. With a master's degree in jazz saxophone from the University of North Texas, Ashley has an unconventional background that gives her science writing a unique perspective and an outsider's point of view.

Most Popular