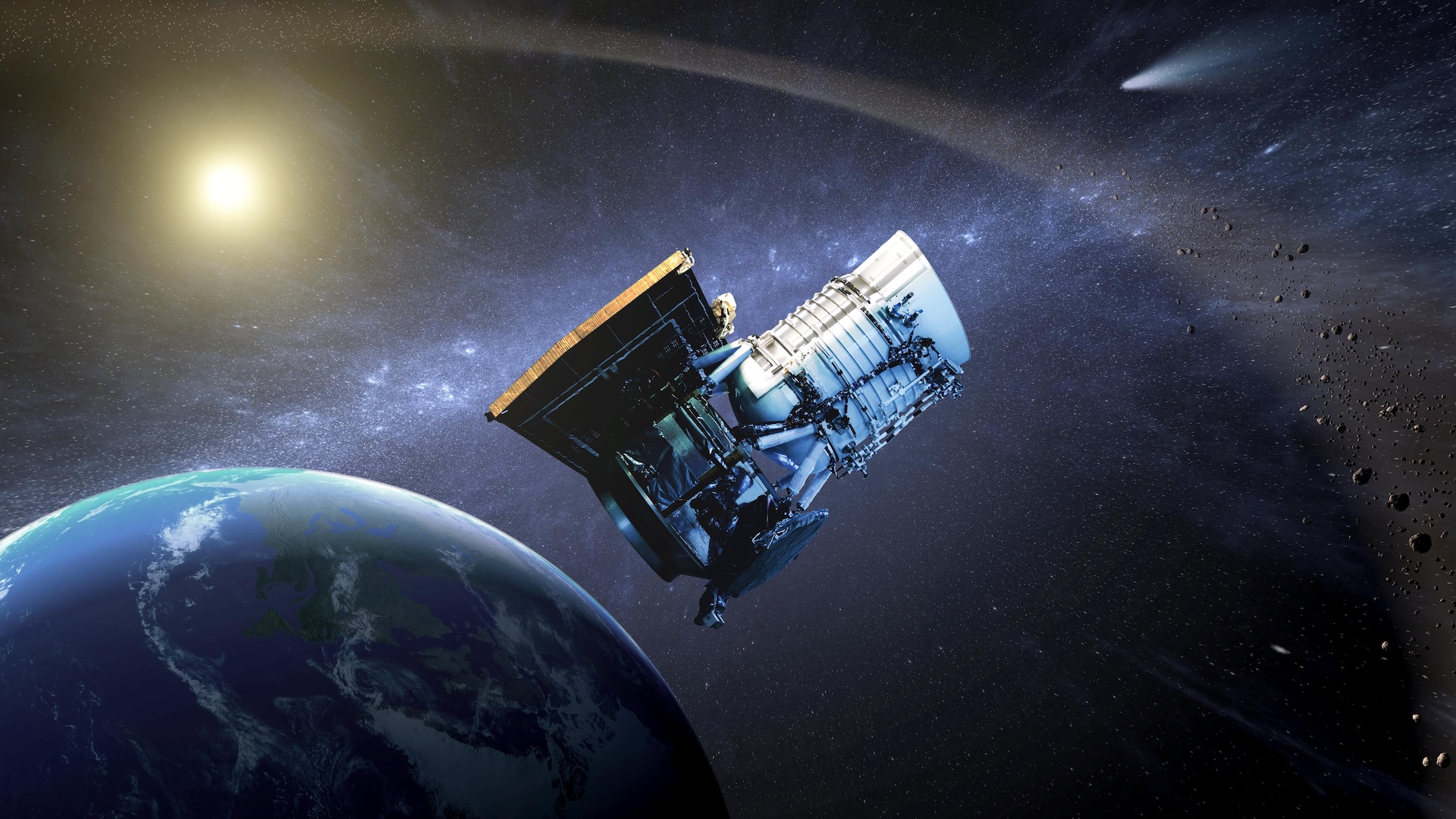

NASA shuts down down asteroid-hunting NEOWISE telescope as the sun drags it to its doom

NASA's asteroid-hunting NEOWISE space telescope will soon plunge into Earth's atmosphere and burn to bits. Here's a look back at its epic mission that defied all expectations.

NASA's only space telescope dedicated to planetary defense has turned off its transmitter for the last time, ending its 15-year career detecting near-Earth asteroids and comets.

The spacecraft — named NEOWISE (Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer) — vastly outlived its original seven-month mission to scan the sky for infrared signals. It ultimately detected more than 200 previously unknown near-Earth objects, including 25 new comets, and provided a wealth of data on 44,000 other objects that zoom through our solar system, according to NASA.

NEOWISE's mission, which officially ended on July 31, is finally coming to an end as the sun's era of peak activity, called solar maximum, threatens to drag the satellite into Earth's atmosphere for a final, fiery reentry. The spacecraft, which lacks propellant to thrust itself into a higher orbit, has been steadily falling toward Earth for years and is expected to safely burn up in the atmosphere in late 2024.

"This telescope has really outlived its original [lifespan]," Amy Mainzer, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles and principal investigator for both NEOWISE and its planned successor, NEO Surveyor, told Live Science in an interview last year. "We got so much more out of it than we were expecting to get."

Related: 'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

Retirement and rebirth

NEOWISE launched in 2009 as simply WISE, the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. Like a prototypical version of the James Webb Space Telescope, WISE entered orbit with a mission to map the entire sky in infrared light, looking for traces of faint and ancient emissions from the early universe.

Its original seven-month mission showed that WISE was far more sensitive than scientists had expected. NASA then extended the mission under the name NEOWISE to last until 2011, so the telescope could survey the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The telescope was then put into hibernation after running out of coolant, which kept the spacecraft's heat from leaching into NEOWISE's infrared sensors and reducing their sensitivity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, later analysis of the telescope's data showed it was still capable of detecting nearby solar system objects that reflect sunlight. Thus, NEOWISE was brought out of hibernation in 2013 to continue its survey of near-Earth objects for another decade.

Among the hundreds of objects the telescope discovered, its most famous detection is the bright comet that bears its name: comet C/2020 F3 NEOWISE, which zoomed past Earth in July 2020.

A gap in the skies

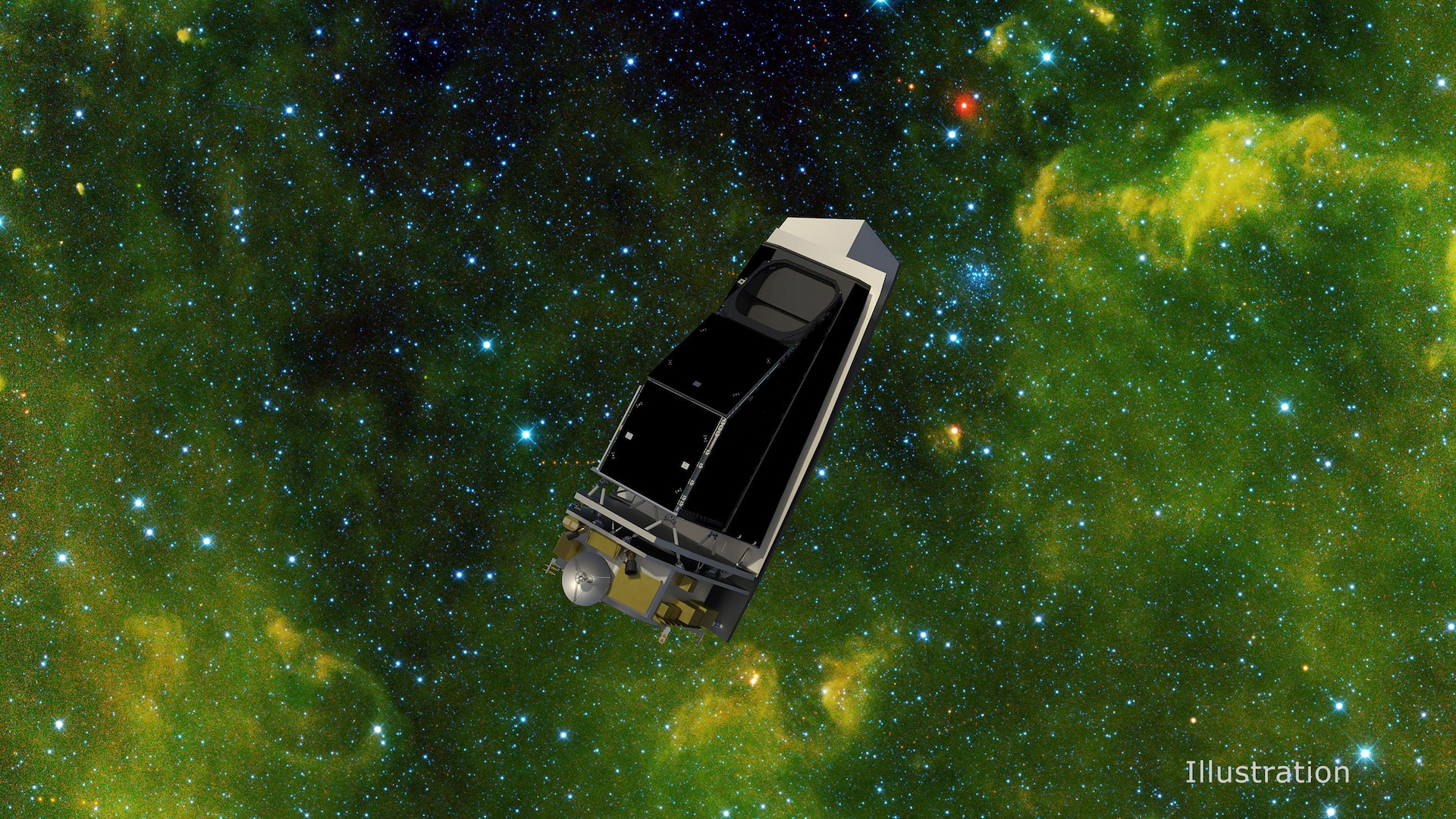

The demise of NEOWISE leaves a temporary planetary defense gap in Earth's orbit. No other NASA space telescope devotes 100% of its time to hunting for near-Earth objects, some of which could pose a danger to our planet.

However, an even more powerful infrared telescope called NEO Surveyor is already in the works to continue NEOWISE's mission, with a planned launch date of no sooner than 2027. Once deployed, NEO Surveyor will complete a full scan of the sky every two weeks, Mainzer said. A purpose-built solar shade will also allow the telescope to hunt for asteroids located near the glare of the sun — a region of space that's considered our biggest planetary defense blind spot.

In the meantime, scientists will rely on powerful ground-based observatories to make sure no pesky near-Earth asteroids sneak up on us.

"We'll have the ground based telescopes, and these days they find the majority of the objects anyway," Mainzer said. "Catalina Sky Survey [in Arizona] and Pan-STARRS [in Hawaii] are the two surveys that are discovering the largest number of objects right now, and that's been that way for a long time."

With the help of surveys like these, astronomers have mapped the orbits of more than 34,000 near-Earth asteroids, according to NASA — and none pose a threat to Earth for at least the next 100 years.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.