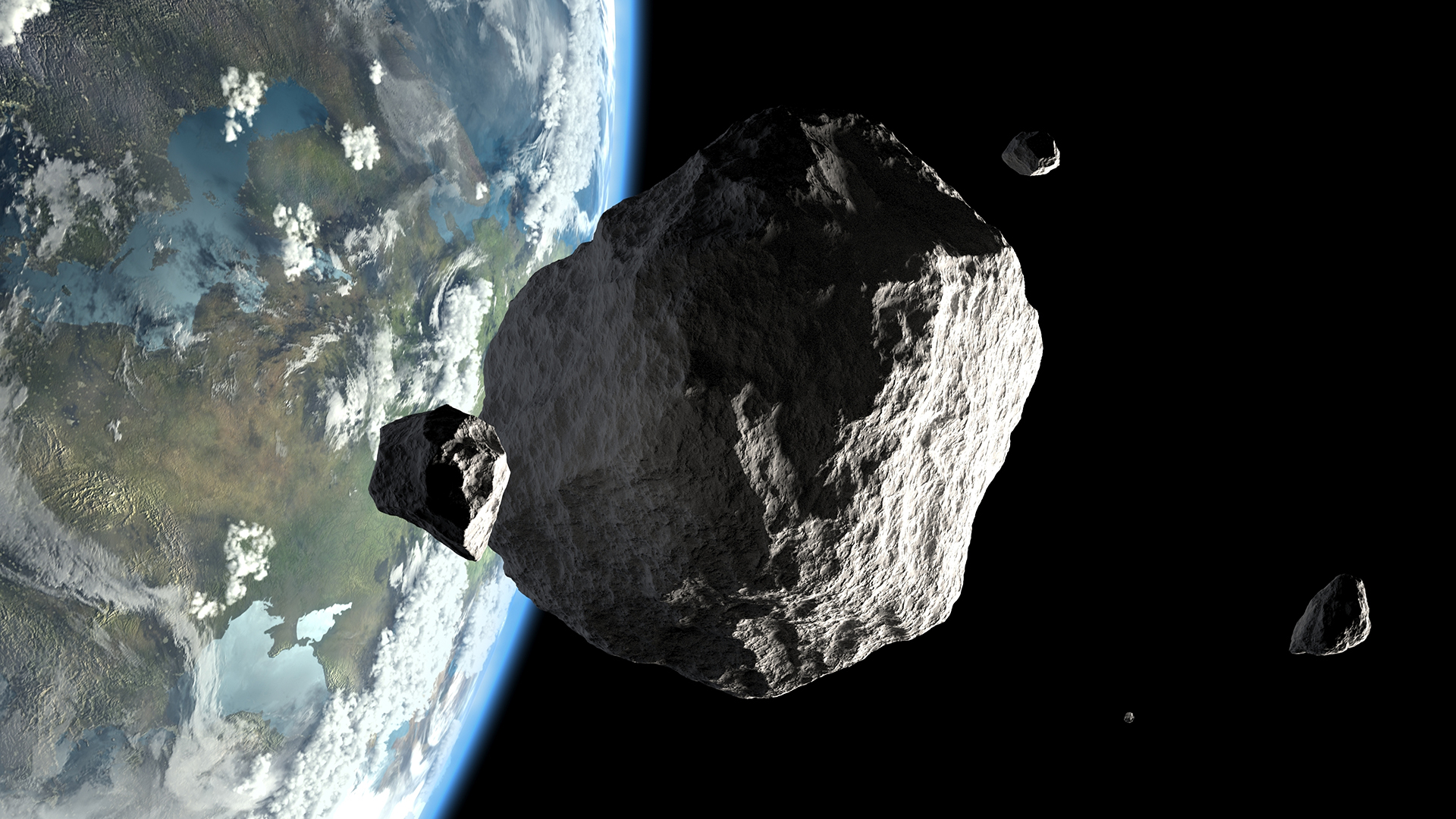

5 asteroids will skim past Earth over the next 2 days, NASA says

The five asteroids range from plane to bus-size, and one is expected to come to within half a million miles of Earth.

Earth is being visited by five asteroids this week, the biggest of which each about the size of a plane. They will all likely zoom harmlessly past our planet, NASA said.

The five asteroids, the smallest of which are bus-size, are skimming across Earth's orbit between Friday (Sept. 8) and Saturday (Sept. 9), according to NASA's Asteroid Watch database.

The first is the roughly 39-foot-wide (12 meters) asteroid 2023 RG, which will fly past Earth at a distance of 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) on Friday. Later on the same day, the 88-foot-wide (27 m) 2023 RH, 82-foot-wide (25 m) 2023 QC5 and 26-foot-wide (8 m) 2020 GE will approach to within 1 million miles, 2.5 million miles (4. million km) and 3.6 million miles (5.7 million km) of Earth respectively. .

Related: NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission almost bit the dust — then Queen guitarist Brian May stepped in

Finally, the 24-foot-wide (7 m) asteroid 2023 RL will zip past Earth at a cosmically tiny distance of 469,000 miles (755,000 km) on Sept. 9.

NASA flags any space object that comes within 120 million miles (193 million km) of Earth as a "near-Earth object" and classifies any large object within 4.65 million miles (7.5 million km) of our planet as "potentially hazardous." NASA tracks the locations and orbits of roughly 28,000 asteroids, following them with the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS), an array of four telescopes that can perform a scan of the entire night sky every 24 hours.

NASA has estimated the trajectories of all these near-Earth objects beyond the end of the century. Earth faces no known danger from an apocalyptic asteroid collision for at least the next 100 years, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If the five fast-approaching asteroids were to smash into Earth, they would not cause a cataclysmic event like the 7.5-mile-wide (12 km) dinosaur-killing asteroid that struck Earth 66 million years ago. But this doesn't mean smaller asteroids aren't dangerous. In March 2021, for example, a bowling ball-size meteor exploded over Vermont with the force of 440 pounds (200 kilograms) of TNT.

Even more dramatically, a 2013 explosion of a 59-foot-wide (18 m) meteor above Chelyabinsk, Russia, generated a blast roughly equal to around 400 to 500 kilotons of TNT, or 26 to 33 times the energy released by the Hiroshima bomb, and injured around 1,500 people.

Understanding the trajectories of asteroids can be a harder task than it first appears because of the so-called Yarkovsky effect. Named after the 19th-century engineer who first proposed it, over long periods of time space rocks such as asteroids absorb and emit enough momentum-carrying light to subtly change their orbits. This means that quantifying the Yarkovsky effect is crucial when predicting which asteroids are potential threats.

Space agencies around the world are already working on possible ways to deflect a dangerous asteroid if one ever headed our way. On Sept. 26, 2022, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft redirected the non-hazardous asteroid Dimorphos by ramming it off course, altering the asteroid's orbit by 32 minutes in the first test of Earth's planetary defense system. NASA has since hailed the mission as a success beyond all expectations.

China has also suggested it is in the early planning stages of an asteroid-redirect mission. By slamming 23 Long March 5 rockets into the asteroid Bennu, which will swing within 4.6 million miles (7.4 million km) of Earth's orbit between the years 2175 and 2199, scientists hope to divert the space rock from a potentially catastrophic impact with our planet.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.