8 strange objects that could be hiding in the outer solar system

The outer solar system is a vast and mysterious place that could be harboring hidden objects we know almost nothing about — from the elusive Planet Nine and baby black holes to interstellar visitors and "planet killer" asteroids.

You might think we know the solar system pretty well, but there's a lot more to our cosmic neighborhood than initially meets the eye (or telescope).

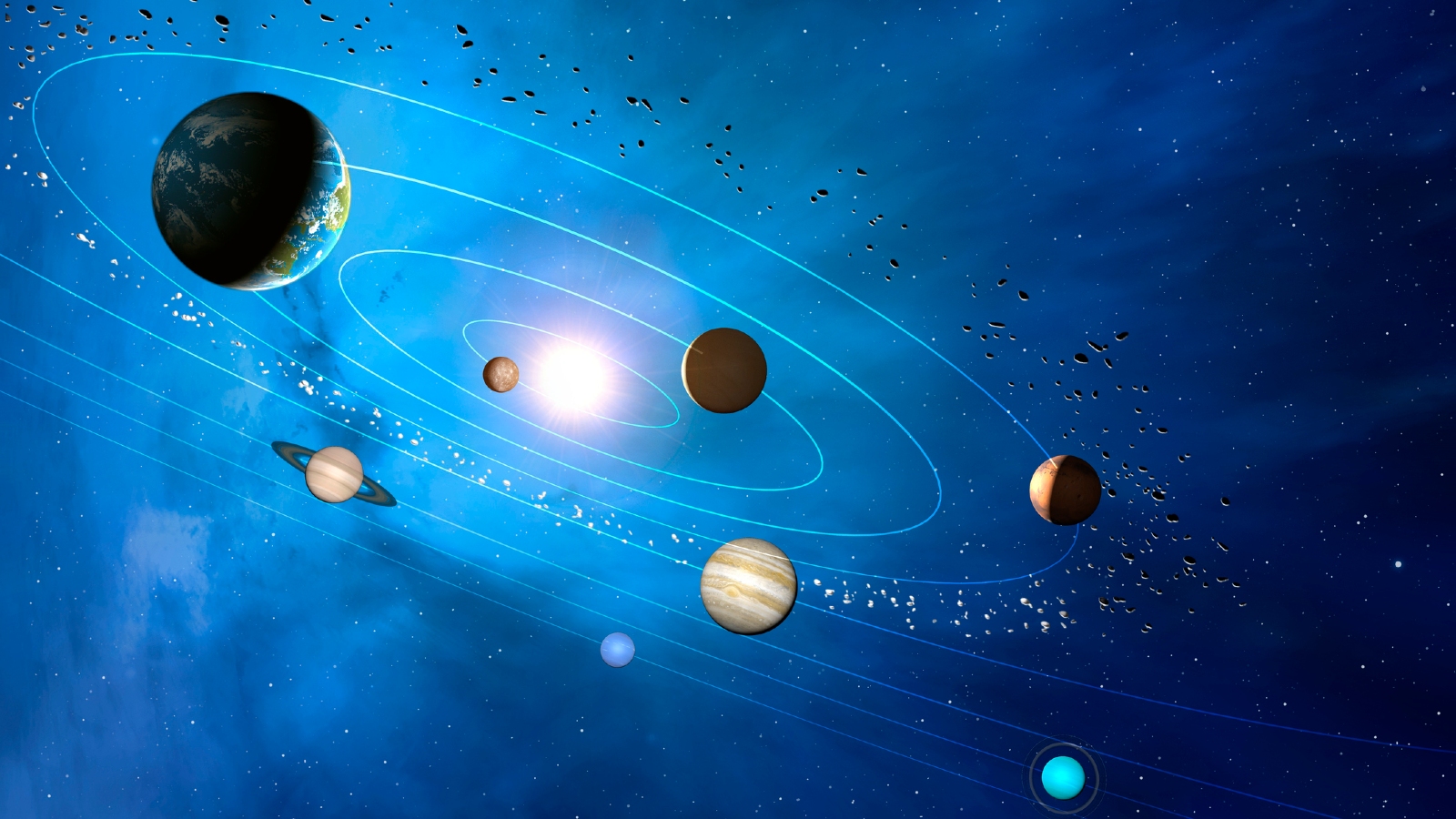

Most of the good stuff, such as the planets, moons and asteroid belt, are grouped relatively tightly toward the solar system's center and are illuminated by the sun's glare, making them somewhat easy to spot. But if you look toward the edge of the solar system, you'll find a vast, dark place in which mysterious entities can easily hide. As a result, researchers have had a field day thinking up all the things that could be lurking out there.

From a massive ninth planet and a second Kuiper belt to interstellar visitors and mini-black holes, here are eight hypothetical objects that could be lurking in the darkness.

Related: 10 out-of-this-world solar system discoveries made in 2023

Planet Nine

The largest and most controversial object that could be lurking in our cosmic neighborhood is a hypothetical ninth planet dwelling far beyond the other known solar system worlds, which researchers have creatively nicknamed "Planet Nine."

Scientists first proposed Planet Nine in 2016 to explain the eccentric orbits of several large objects in and around the Kuiper Belt — a massive ring of asteroids and other rocky objects that circle the sun beyond the orbit of Neptune. Some researchers believe these objects are being gravitationally tugged by a massive, unknown world beyond the Kuiper Belt. However, despite finding even more of these objects in recent years, the actual planet has evaded detection — so far.

If it does exist, Planet Nine is likely an icy gas giant around seven times more massive than Earth, which would make it the fifth-largest planet in the solar system. However, the planet could be extremely far away, possibly orbiting our sun once every 10,000 years, which means it would be very faint and extremely hard to spot.

Researchers have narrowed down the area where Planet Nine could be hiding but are limited by the strength of the telescopes currently available. However, with new state-of-the-art telescopes soon coming online, it could be discovered within the next few years, experts recently told Live Science.

Baby black holes

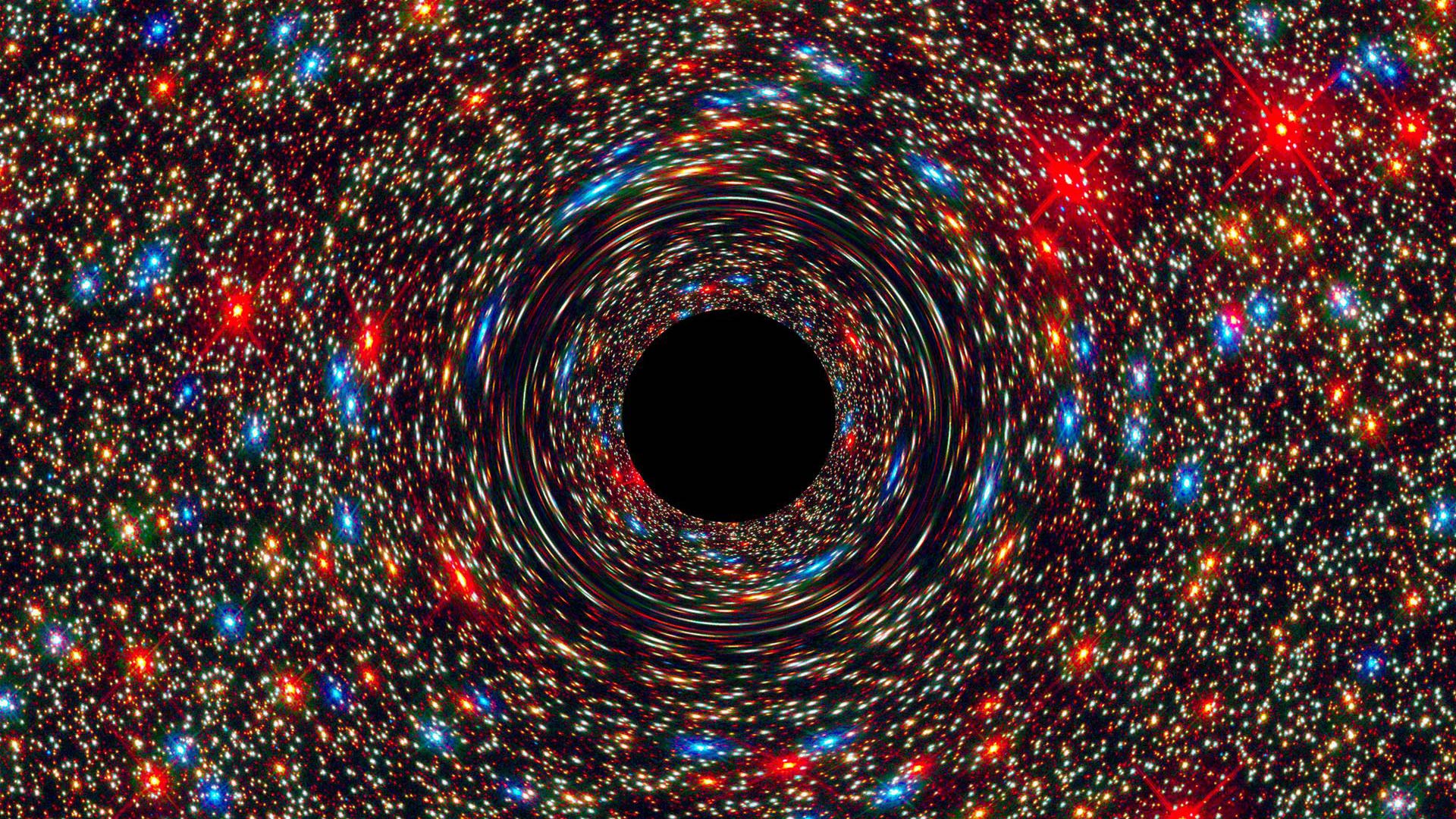

Not everyone believes that Planet Nine is responsible for the orbital anomalies of Kuiper Belt objects. Other scientists believe that something equally hard to spot could be gravitationally tugging on these distant space rocks — a mini black hole.

Researchers argue that a black hole that's around the size of a moon or planet could exert the same gravitational force as the supposed Planet Nine. Black holes of this size are theoretically possible but have never been observed, which makes this idea somewhat controversial. To prove this theory, researchers would probably need to detect Hawking radiation coming from the black hole or watch something fall beyond its event horizon.

But even if a baby black hole is not masquerading as Planet Nine, other researchers believe there could be even smaller "primordial" black holes in the outer solar system and that these supersmall singularities could be making some planets and moons wobble.

Captured alien worlds

Some researchers believe there could be more hidden worlds, other than Planet Nine, in the outer reaches of the solar system.

But unlike Planet Nine, these hypothetical planets — known as rogue planets — may not have originated in our neck of the woods. Instead, they would be castaways from distant stars that may have been pulled in by the sun after drifting in interstellar space for eons.

Scientists have already detected hundreds of rogue planets zooming across the Milky Way. However, in 2023 researchers proposed that a rogue planet could be lurking near the solar system's edge, even further out than Planet Nine. And if that wasn't crazy enough, a 2024 paper also suggested that there is space for up to five Earth-size rogue planets toward the edge of our cosmic neighborhood.

Second Kuiper Belt

The Kuiper Belt could play a key role in detecting hidden worlds within the solar system. But it may also be hiding a secret of its own — a twin.

In 2023, researchers announced the potential discovery of a dozen new rocky objects lurking beyond the Kuiper Belt. These hefty space rocks, which are likely all asteroids, are located around 10 astronomical units (10 times further than the distance between Earth and the sun) from the majority of the Kuiper Belt — suggesting they could belong to a second, smaller belt of asteroids.

However, other surveys have failed to identify any more of these extra-Kuiper Belt objects, which has left this theory in limbo for now.

More dwarf planets

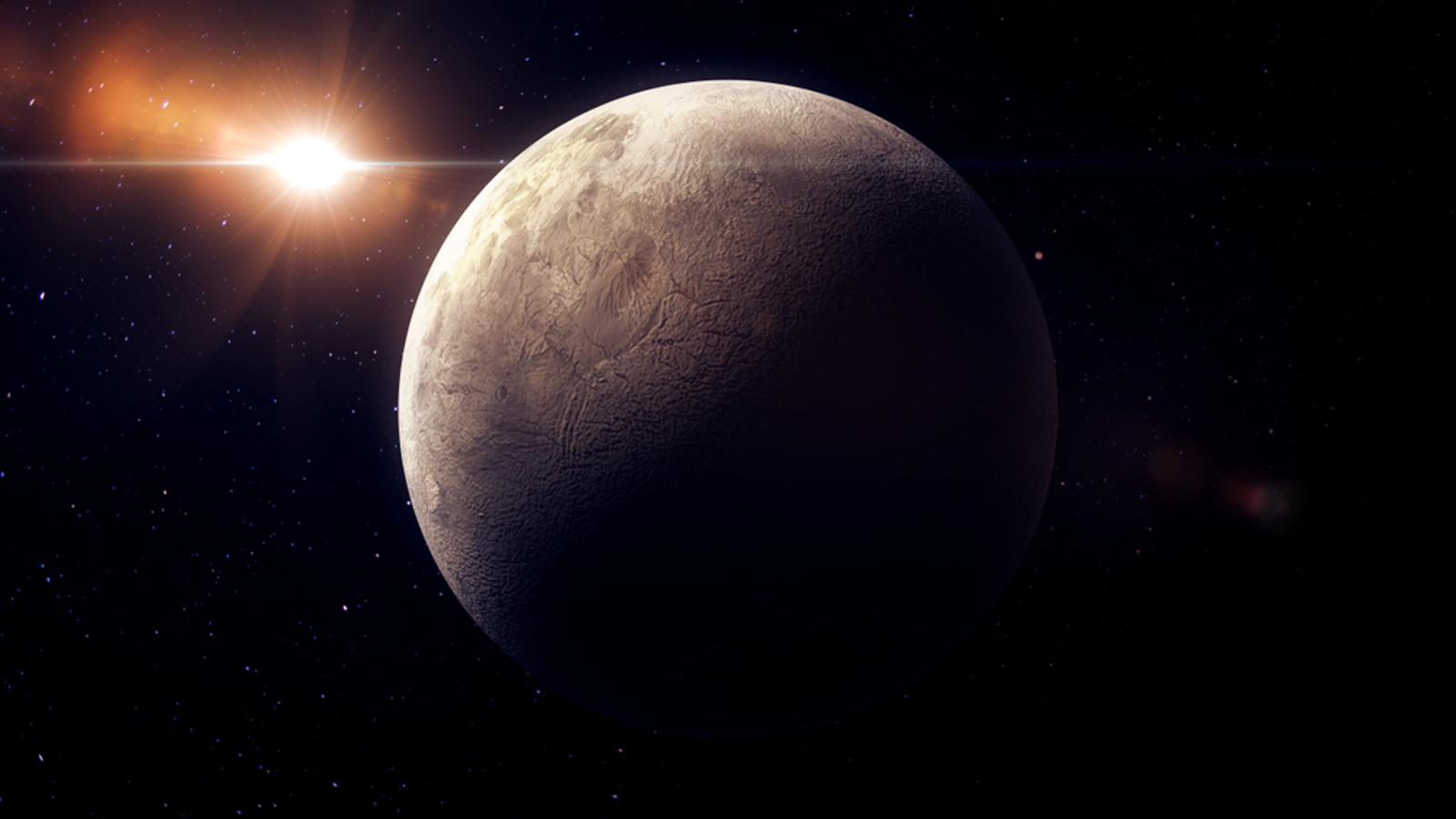

After fully fledged worlds and missing asteroid belts, the next largest objects that could be hiding under our noses are dwarf planets — large space rocks that are big enough to be gravitationally rounded, like planets, but not big enough to completely clear their orbital pathway of debris.

The solar system harbors five known dwarf planets: Ceres, Haumea, Eris, Makemake and the ex-planet Pluto, according to NASA. Other candidates such as Gonggong, Quaoar and Sedna are not officially recognized as dwarf planets but are often referred to as such by astronomers.

All of these mini-worlds lie within the Kuiper Belt or beyond — apart from Ceres, which is located in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. But as we have already seen, there are plenty of places for objects to hide in the outer solar system. Some estimates suggest there could be dozens or even up to a hundred dwarf planets still waiting to be discovered, according to the International Astronomical Union.

Until recently, researchers believed that the dwarf planets were mostly geologically dead, except for Pluto, which has an icy supervolcano. However, new data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope revealed that Eris and Makemake may also be geologically active, which increases the chances they or other future dwarf planets could harbor alien life.

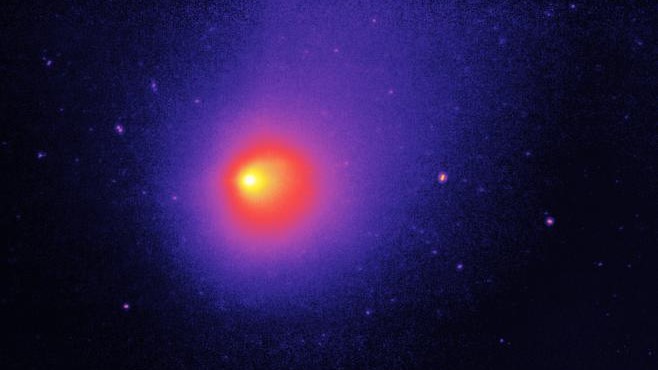

Volcanic comets

Far beyond the Kuiper Belt lies a gigantic reservoir of comets known as the Oort Cloud, which extends to around 1,000 astronomical units from the sun. A very small percentage of these icy objects are what researchers refer to as cryovolcanoes, or cold volcanoes, that shoot dust and frozen gas into space when they erupt.

Cryovolcanic comets only erupt near the sun, when solar radiation causes intense pressure to build up within their outer shells, or nuclei, eventually triggering explosive outbursts. However, most comets have highly elliptical orbits, meaning they spend a majority of their orbits floating in the outer solar system before sweeping into the inner solar system every few decades or centuries. This makes it hard to spot which ones are cryovolcanic.

For example, Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, also known as the "devil comet," made its closest approach to the sun for around 71 years when it slingshotted around our home star in April 2024. Since June 2023, when the comet began its dive bomb into the inner solar system, the comet has been spotted erupting multiple times. But for the preceding 69 years, astronomers didn't see it explode once.

As a result, astronomers suspect that many more cryovolcanic comets are hiding in plain sight within the Oort Cloud and that we'll only identify them when they eventually approach the sun.

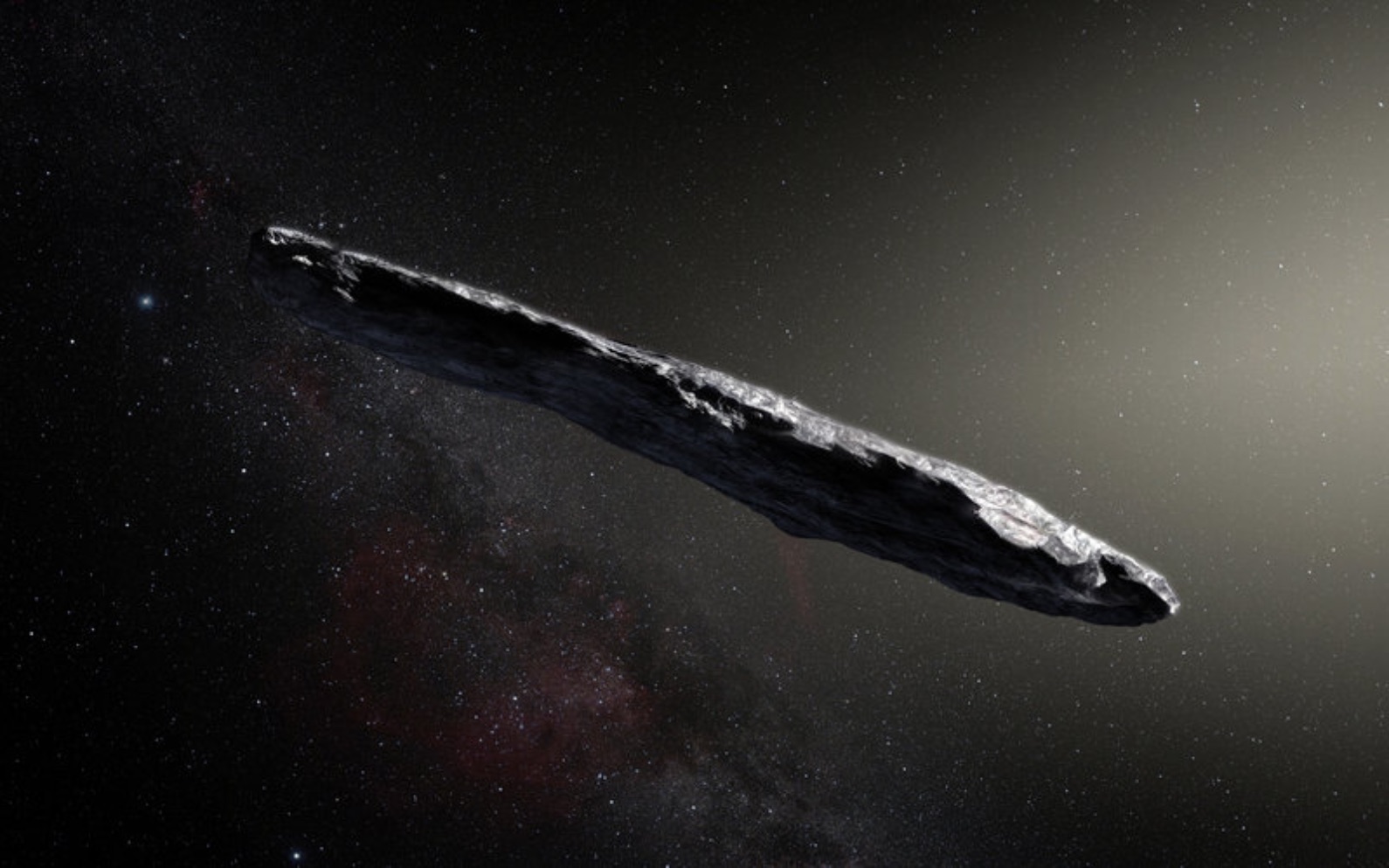

Interstellar visitors

In addition to suspected rogue planets, the sun's gravitational might is also capable of pulling in other free-floating objects from interstellar space. However, unlike the supposed captured worlds, a majority of these objects likely pass through our cosmic neighborhood and never return.

Astronomers have already spotted two confirmed interstellar objects: 'Oumuamua, an oblong object that made headlines in 2017 after some researchers mistakenly suggested that it could be an alien probe; and Comet 2I/Borisov, which was spotted in 2019 as it sailed through the solar system. Other researchers suspect that a tiny meteor that exploded over Earth in 2014 was also an interstellar interloper.

Given the tiny number of confirmed sightings, you'd be forgiven for thinking that interstellar objects are rare. However, some researchers estimate that there are between 1,000 and 10,000 of these objects in the solar system at any one time, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com.

Some researchers have proposed the creation of special "interstellar interceptor" spacecraft that could be stashed in orbit around Earth so that scientists can quickly chase and study new objects as soon as they are discovered. But at present, there are no official plans for such spacecraft.

Killer asteroids

The final objects on this list are the most dangerous. But thankfully, they are among the least likely to be found.

The inner solar system is filled with potentially hazardous asteroids, which orbit the sun close enough to Earth to be considered a threat to our planet (even though most will never get anywhere near us). These perilous space rocks can range in size from "city killers" that could wipe out large population centers to "planet killers" like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Similar massive rocks reside in the Kuiper Belt and beyond. However, unlike comets, asteroids don't usually migrate in and out of the inner solar system, meaning these rocks do not pose much threat to us. But this doesn't mean it's impossible. If a massive asteroid did venture toward Earth it could also be obscured by the glare of the sun, depending on its position, which could give us very little warning before it snuck up on us.

Scientists calculate that potentially hazardous asteroids pose no threat to Earth for at least 1,000 years. However, that calculation is based solely on the space rocks we know about.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.