Betelgeuse, Betelgeuse? One of the brightest stars in the sky may actually be 2 stars, study hints

Betelgeuse, one of the brightest stars in the sky, may have a secret sunlike companion that drives the star’s mysterious six-year-long "heartbeat," new research suggests.

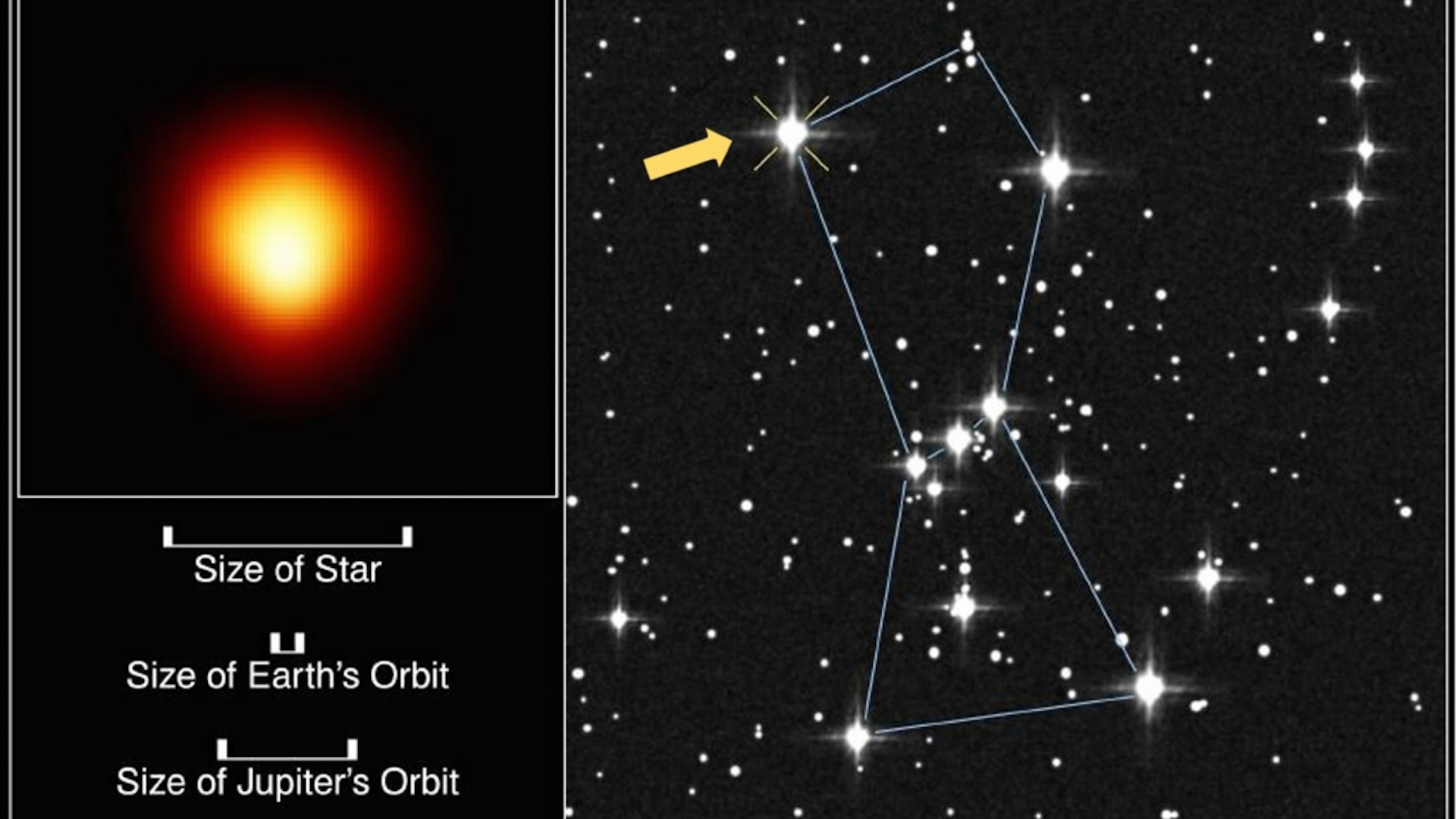

The iconic star Betelgeuse, which is part of the constellation Orion, is one of the brightest stars visible from Earth and one of the most observed celestial objects in the night sky — but it may not be alone.

A new theoretical study proposes that Betelgeuse has a sunlike companion that orbits it and may be responsible for its perplexing periodic brightening.

If you train a telescope on Betelgeuse for weeks, you'll see it dimming, then brightening, then dimming again. These pulsations stretch over roughly 400 days, although the 2020 "Great Dimming" event reveals such periodicity may occasionally go awry. But if you plotted Betelgeuse's light intensity over years, you'd find these 400-day-long heartbeats superimposed on a much larger, slower heartbeat. Technically called a long secondary period (LSP), this second type of heartbeat lasts about six years, or 2,170 days, in Betelgeuse's case.

"There are a lot of stars that exhibit LSPs, but most of them are not like Betelgeuse: most have lower masses," Meridith Joyce, an assistant professor at the University of Wyoming told Live Science in an email. Joyce co-authored the new study along with Jared Goldberg of the Flatiron Institute in New York City and László Molnár of the Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences in Hungary.

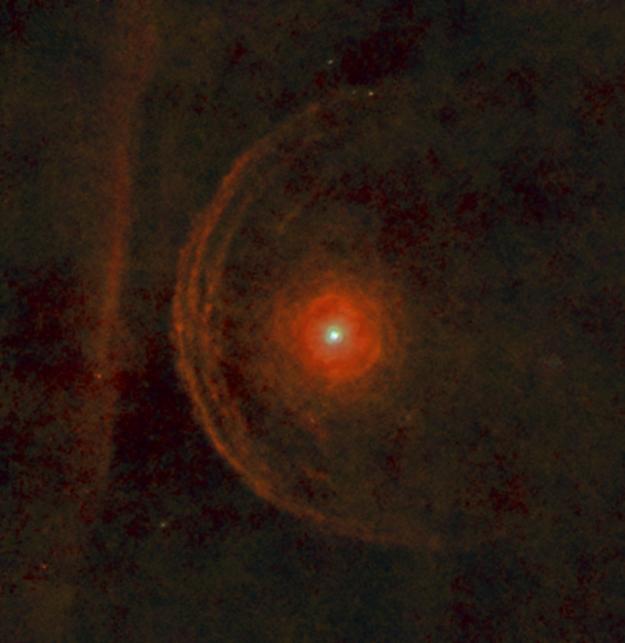

Periodic changes in a star's brightness typically occur when the star swells and then shrinks, again and again. This happens because gas near the star's core gets super-heated and rises to the surface, where it expands ― causing the star's size to increase ― but then cools and settles back towards the interior, shrinking the star. The general consensus among astronomers is that Betelgeuse's 400-day-long pulsations arise from such cycling. But the cause of the star's 2,170-day-long LSP had remained elusive, despite several possible theories, including the presence of gigantic dust clouds.

The astronomers explored a range of phenomena that could generate large, slow pulsations in brightness. These included differences in the rotation rate of the star's core versus its surface, as well as sunspot-like star spots created by Betelgeuse's chaotic magnetic fields, driven by electrically conducting fluids within the star.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ultimately, only one scenario could explain all of Betelgeuse's parameters: a companion star that plows through dust clouds enveloping Betelgeuse.

According to the team's hypothesis, when the companion star — which the team calls "Betelbuddy" — sails into view of Earth, it temporarily disperses the clouds of dust surrounding its partner. Because this dust typically blocks Betelgeuse, its absence causes the star to look brighter from Earth's point of view.

The team's calculations suggest that Betelgeuse's buddy is much bigger than a planet and might be up to two times as massive as the sun. However, Joyce said this isn't conclusive; she personally believes Betelbuddy may be a neutron star, the ultradense core of a collapsed star. In that case, though, "we would expect to see evidence of this with X-ray observations, which we haven't," she said.

Although no previous research has suggested that Betelgeuse has a companion, Joyce said this isn't entirely unexpected considering the statistics; most stars possess one, or even two, sidekicks. Still, verifying this prediction will require direct observations of the binary companion, and that may be difficult with current technology. Nonetheless, Joyce and her team "are in the midst of putting together a few observing proposals. … The first window of opportunity is this coming December."

The study, which hasn't been peer-reviewed, is available as a preprint on the arXiv server.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Sept. 12 to include the names of all three researchers who participated in the study.

Deepa Jain is a freelance science writer from Bengaluru, India. Her educational background consists of a master's degree in biology from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and an almost-completed bachelor's degree in archaeology from the University of Leicester, UK. She enjoys writing about astronomy, the natural world and archaeology.