Does the Milky Way orbit anything?

Do galaxies, including our own Milky Way, orbit anything in the universe?

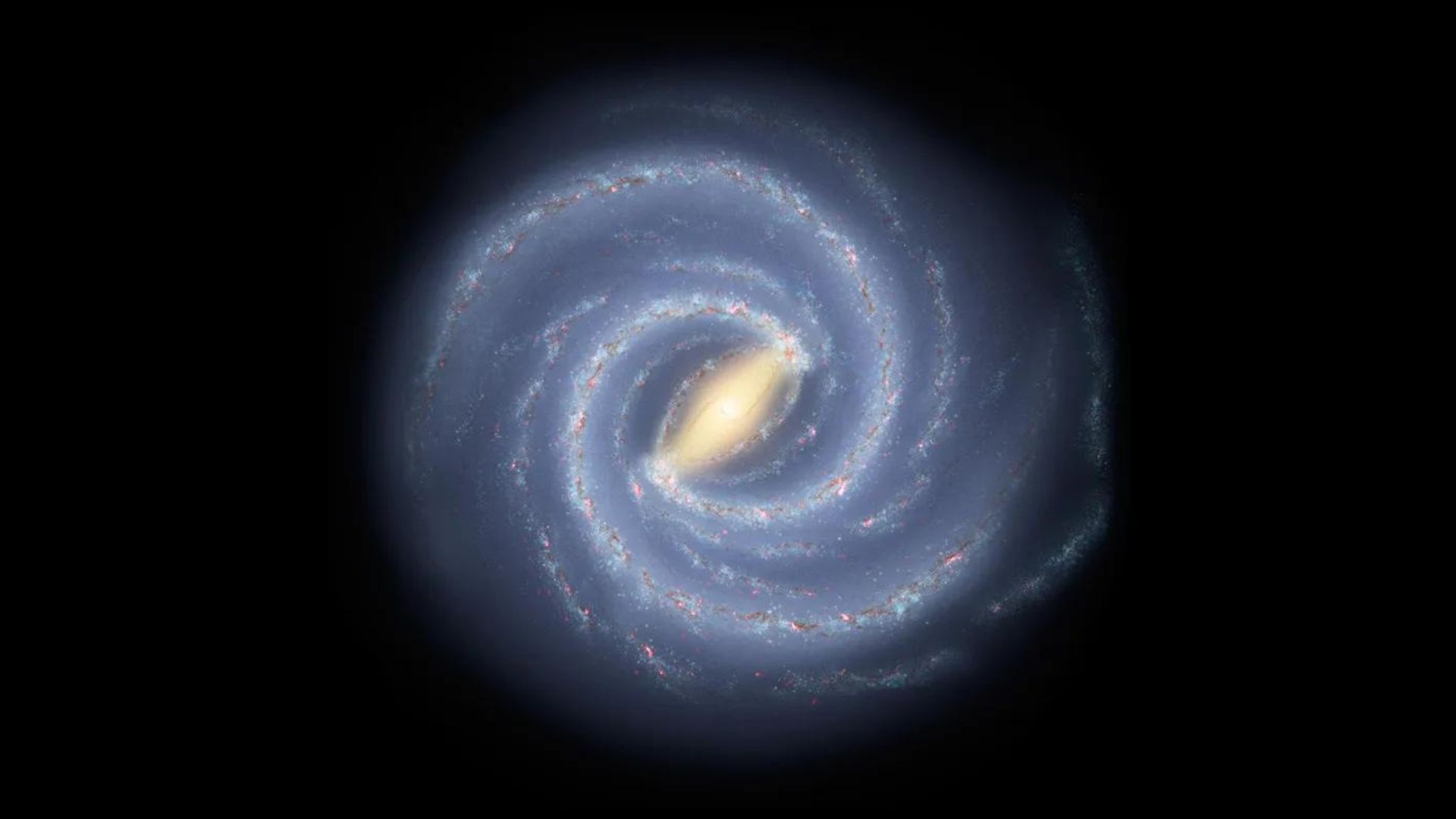

It seems like everything orbits something in space. Moons orbit planets. Planets orbit stars. Stars orbit the centers of galaxies. But beyond that, things get a little harder to visualize. Do galaxies — and, specifically, the Milky Way — orbit anything?

To answer that, we first need to know how orbits work. Consider two objects orbiting each other. Those two bodies exert a gravitational pull on each other, keeping them bound together. The objects orbit their common center of mass — if you could shrink the system, the center of mass would be the point where you could balance it on your finger. But in the case of the solar system, or Earth and the moon, one of the objects is much larger than the other. The center of mass ends up lying inside the larger body, so the larger object doesn't move much and the smaller object moves on a roughly circular path around the bigger one.

At larger scales, things get a little more complicated. Our galaxy is part of a collection of galaxies called the Local Group, which includes the Milky Way; the Andromeda galaxy; a smaller spiral galaxy called Triangulum; and several dwarf galaxies, including the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. The Milky Way and Andromeda are the two largest objects in the Local Group. Because their masses are comparable, the center of mass lies between the two galaxies, said Sangmo Tony Sohn, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland. There's nothing significantly larger than either galaxy nearby, so the two end up orbiting each other.

But the Milky Way's orbit isn't circular or elliptical like the orbits of planets around the sun. "It's going to be weird to say if the Milky Way is orbiting around something, because that kind of implies that there's a bigger object," Sohn told Live Science. "But that's not the concept here."

Related: Why aren't all orbits circular?

Instead, both the Milky Way and Andromeda are on mostly radial orbits. "Imagine the gravity of two things pulling on each other, and they're not moving in any way other than the gravitational pull. They will just move directly on the line towards each other. That's a purely radial orbit," said Chris Mihos, an astronomer at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. The Milky Way's orbit isn't perfectly radial because there's a bit of sideways motion between the two galaxies, Mihos told Live Science.

Their mostly radial orbits toward each other mean that the Milky Way and Andromeda will eventually collide, some 4.5 billion years from now. Individual stars likely won't crash into each other because of the huge distances between them, so the galaxies will pass through each other and separate again — but not for long.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The galaxies [will] then turn around and come back together. And, over the course of hundreds of millions or billions of years, they'll actually merge together into one big galaxy," Mihos said.

The gravitational interactions will likely jostle the stars in both galaxies enough to make the combined galaxy an elliptical galaxy rather than a spiral one like the Milky Way and Andromeda. The merger could also heat the gas along each galaxy's spiral arms enough to form new stars, Sohn said.

Orbits on scales larger than galaxy groups are even less defined, but "we certainly know the Local Group is moving," Mihos said. The Local Group is being pulled toward the Virgo Cluster, which contains several hundred galaxies and lies about 65 million light-years away. But the Local Group will never make it there, Mihos said, because the expansion of the universe is pulling the Milky Way away faster than the gravitational pull of the Virgo Cluster is drawing it in.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.