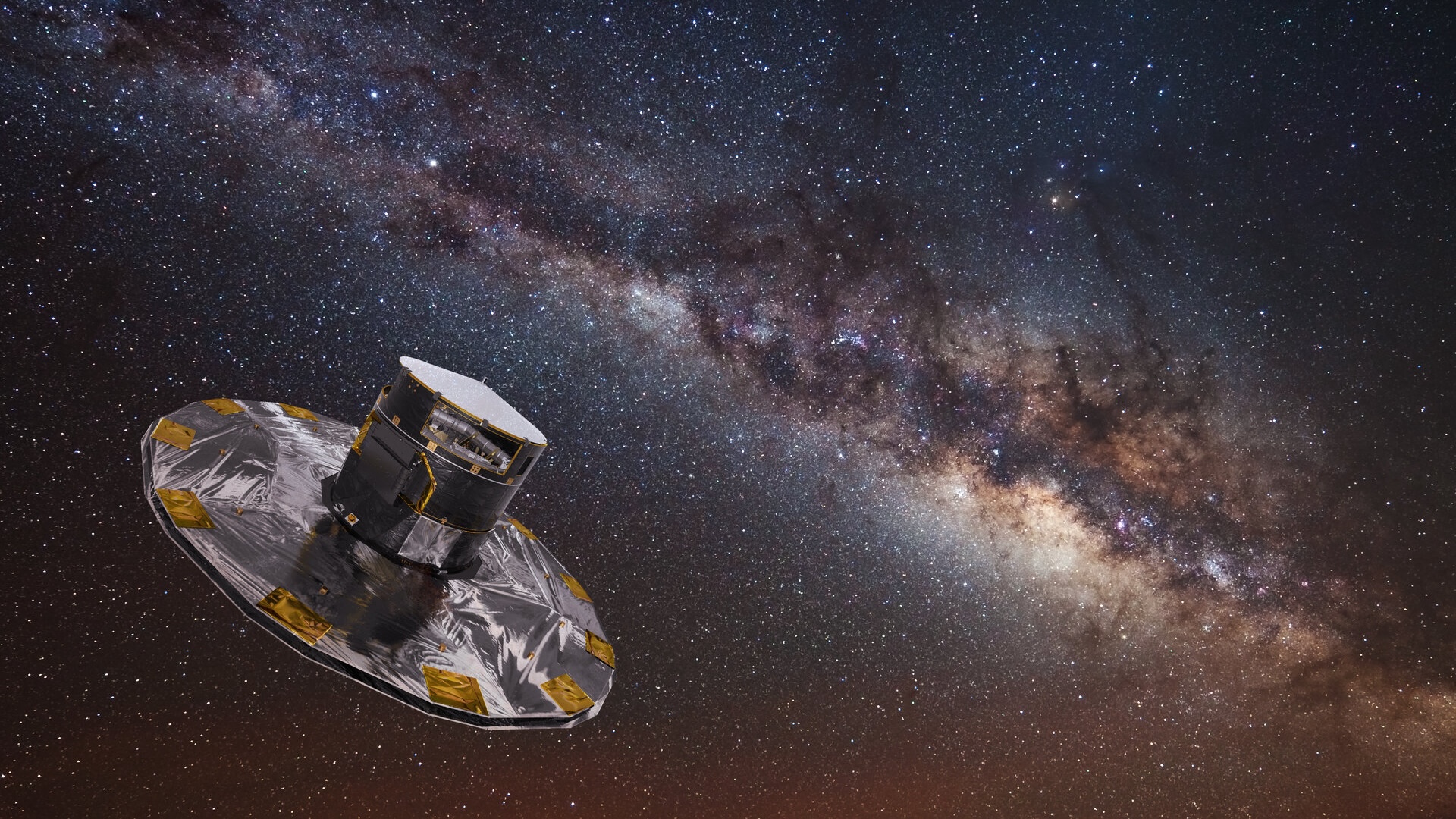

Gaia telescope retires: Scientists bid farewell to 'the discovery machine of the decade' that mapped 2 billion Milky Way stars

After 11 years mapping the Milky Way, the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope has retired. Scientists hailed it as "the discovery machine of the decade."

On March 27, scientists bid farewell to the Gaia telescope, bringing to a close its groundbreaking 11-year mission of mapping the Milky Way and our cosmic neighborhood.

Though not as famous as some of its peers like the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes, Gaia has reshaped our understanding of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Since 2014, the European Space Agency's (ESA) telescope has meticulously charted the cosmos, creating a vast catalog of nearly 2 billion stars, more than 4 million potential galaxies and around 150,000 asteroids, with moons possibly circling hundreds of them.

These observations have led to more than 13,000 scientific studies, with many more likely to follow in the coming years.

"Gaia's extensive data releases are a unique treasure trove for astrophysical research, and influence almost all disciplines in astronomy," Johannes Sahlmann, a physicist at the European Space Astronomy Centre in Spain and a project scientist for the Gaia mission, said in a statement.

After 11 years of operations — nearly double its expected lifetime — Gaia ran out of fuel, prompting its operators at ESA to power down and retire the spacecraft.

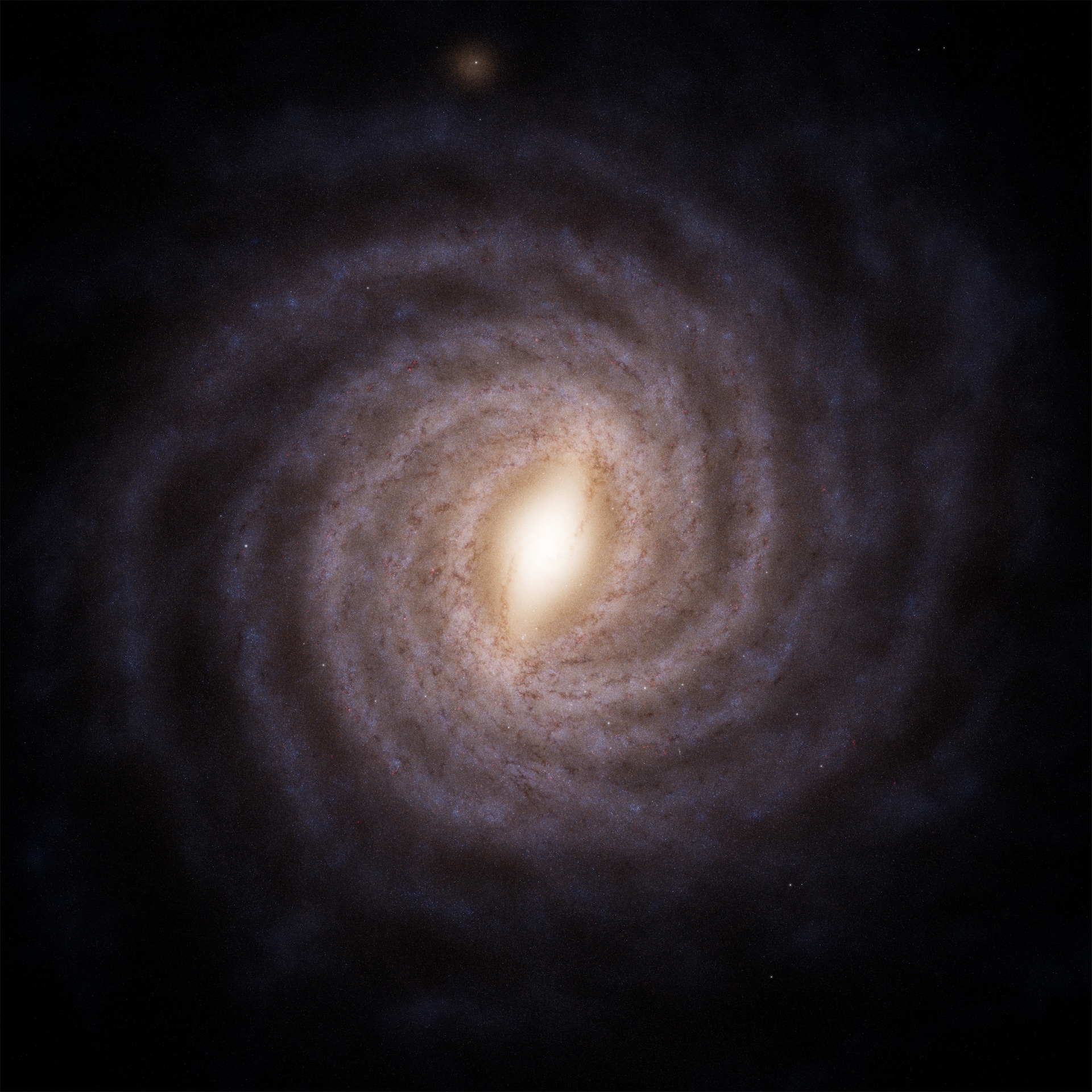

The best map of the Milky Way galaxy

Since it launched in December 2013, Gaia charted the cosmos from a vantage point about a million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Earth, at a spot called Lagrange point 2 (L2), where the gravitational forces of Earth and the sun, and the orbital motion of a satellite balance each other.

Gaia's primary goal was to map the positions and movements of over a billion stars within the Milky Way, creating the largest, most precise 3D map of our galaxy. To do so, it was equipped with twin telescopes pointed in different directions to measure the distances between stars, while three onboard instruments collected data on the positions, velocities, colors as well as chemical compositions of celestial objects.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The exquisite map of our galaxy it assembled has enabled scientists to better understand the galaxy's spiral structure, estimate the shape and mass of the dark matter halo that surrounds the Milky Way, and solve the decades-old mystery of our galaxy's warped and wobbling disk — which is likely due to an ongoing collision with the smaller Sagittarius galaxy.

Additionally, the catalog has provided astronomers with new insights into the ancient nature of parts of our galaxy, suggesting that stars began forming in the Milky Way's disk less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang — far earlier than the previously accepted timeline of 3 billion years.

The telescope's observations have also led astronomers to discover previously hidden stellar streams. For example, in 2020, its database of stars revealed the presence and shape of the largest structure ever observed in our galaxy: a vast ensemble of interconnected stellar nurseries spanning 9,000 light-years, known as the Radcliffe Wave, which may have had a lasting impact on Earth's climate.

"Gaia has changed our impression of the Milky Way," Stefan Payne-Wardenaar, a scientific visualiser at the Heidelberg University in Germany, said in a previous statement.

The spacecraft has serendipitously captured thousands of starquakes — tiny motions on surfaces of stars that cause them to swell and shrink periodically — providing unique insights into the inner workings of stars, and spotted high-velocity stars both escaping our galaxy and, surprisingly, racing toward it. It also uncovered several cosmic "sleeping giants," or black holes — one of which is lurking extremely close to Earth.

Gaia's star catalog has also been used to clock the expansion rate of the universe, fueling the ongoing debate over why the expansion seems to be occurring faster than astronomers expected.

"It is impressive that these discoveries are based only on the first few years of Gaia data, and many were made in the last year alone," Anthony Brown, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of Leiden in Netherlands, said in the statement.

Saying goodbye to the 'discovery machine of the decade'

On March 27, ESA commanded Gaia to use its thrusters for the final time, pushing the spacecraft into a "retirement orbit" safely away from Earth and the scientifically important L2 orbit, which is also home to the James Webb Space Telescope, Euclid telescope and China's Chang'e 6 orbiter.

Last week the mission team deactivated the spacecraft's instruments, which were designed with multiple redundant systems to ensure it could reboot and resume operations after any failure. To prevent its computers from powering back on in the future, operators deliberately corrupted its onboard software, according to the ESA statement.

"We had to design a decommissioning strategy that involved systematically picking apart and disabling the layers of redundancy that have safeguarded Gaia for so long," Tiago Nogueira, Gaia spacecraft operator, said in the statement. "We don't want it to reactivate in the future and begin transmitting again if its solar panels find sunlight."

As part of this process, some of Gaia's onboard software is being overwritten using farewell messages from its team on Earth, as well as the names of around 1500 people that have contributed to the mission over the years. pic.twitter.com/Kf37OTSHtBMarch 27, 2025

Team members wrote the names of all 1,500 contributors to the Gaia mission into the spacecraft's onboard memory, as well as personal farewell messages and poems.

The telescope may have gone dark, but scientists hope its discoveries will continue to shine brightly. So far, only a third of the mission's data has been analyzed, as processing the vast amount of information — Gaia is expected to have gathered more than 1 petabyte (1 million gigabytes) of data by the end of its mission — takes months. The next batch of science data is set to be released in 2026, covering a little over five years of observations, with the fifth and final release scheduled for 2030, which will encompass the full 10 years of data.

"Gaia has been the discovery machine of the decade, a trend that is set to continue," Brown said in the statement.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.