Hubble telescope spots 'blue lurker' star feeding off of its conjoined siblings

A rare breed of star recently discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope spins faster by feeding on its stellar siblings.

The Hubble Space Telescope has discovered a rare "blue lurker" star that has been feeding on material from its two conjoined siblings.

The fast-spinning star provides a detailed look at the complicated family dynamics of multiple-star systems.

"It's a good mid-evolution snapshot of this system, and maybe it will help us put together a clearer picture of the overall evolution of triple systems," Eric Sandquist, an astronomer at San Diego State University who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Although the blue lurker looks like a classic sunlike star, it spins much faster because it's propelled by the joint power of three stars in one. Hence, it's "lurking" among a population of much slower stars. The "blue" part comes from how hotter stars like this one tend to appear bluer.

The lurker is a member of the open cluster M67, also known as the "King Cobra Cluster." This 4 billion-year-old group of 500 stars, located 2,800 light-years away, is loosely bound by gravity. Because all of these stars are the same age, they generally spin at about the same rate — except for a sprinkling of curiously speedy stars.

"A typical star in the cluster is rotating around once every 25 days," Emily Leiner, an astronomer at the Illinois Institute of Technology, said at a Jan. 13 news conference at the 245th American Astronomical Society meeting in National Harbor, Maryland. “That's comparable to our own sun… [The blue lurkers] were whipping around every few days."

So Leiner and her team pointed Hubble at one of these lurkers to investigate what could explain its peculiarities. They found that it was accompanied by a white dwarf, the burned-out core of a dead star. But this stellar corpse was so massive that it couldn't have possibly been the remains of only one star.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

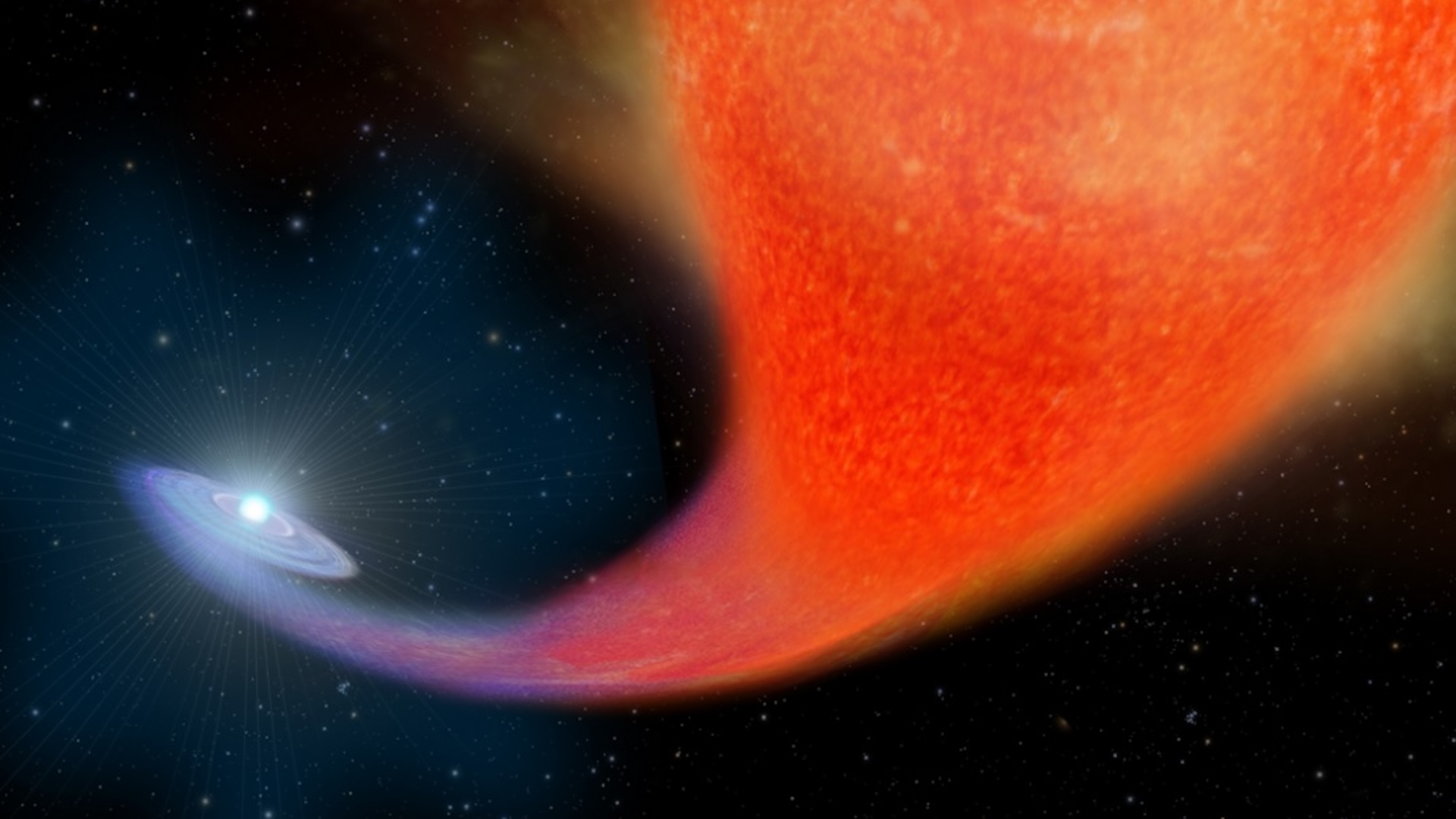

These observations tell the story of a tricky triplet relationship: The lurker started by orbiting two binary stars locked in a do-si-do of sorts. Eventually, the binary stars merged to create a massive star, which swelled later in life. The lurker then siphoned material from the inflated star, which caused the lurker to spin faster and faster as the white dwarf met its demise.

"It's not rare for stars to go through this mass-transfer process; what's harder is finding them," Leiner told Live Science. About 10% of stars fall within triple-star systems like this one, she said, but it's not often that astronomers can trace their evolutionary pathways quite so clearly. Whereas the life cycle of a single star can be predicted easily through modeling, multiple-star systems come with more complexities and thus require detailed observations to begin unraveling their history.

Sandquist is interested in seeing how prevalent blue lurkers are and whether they are tied to other cosmic phenomena, like Type Ia supernovas — a landmark type of explosion used to measure the universe's expansion rate. If lurkers like these turn out to be a common culprit behind Type Ia supernovae, they won't just help us understand triple-star systems but could also shed light on the universe’s evolution.

Jenna Ahart is a physics and astronomy writer who has previously written for NASA and MIT Technology Review. During her bachelor's at George Washington University, she studied journalism and astrophysics, and she's currently pursuing her master's in science communication at the University of California, Santa Cruz.