In 2022, scientists spotted a strange signal coming from the most powerful cosmic explosion ever detected.

Now, scientists say they know what made it: matter and antimatter colliding and annihilating each other at 99.9% the speed of light.

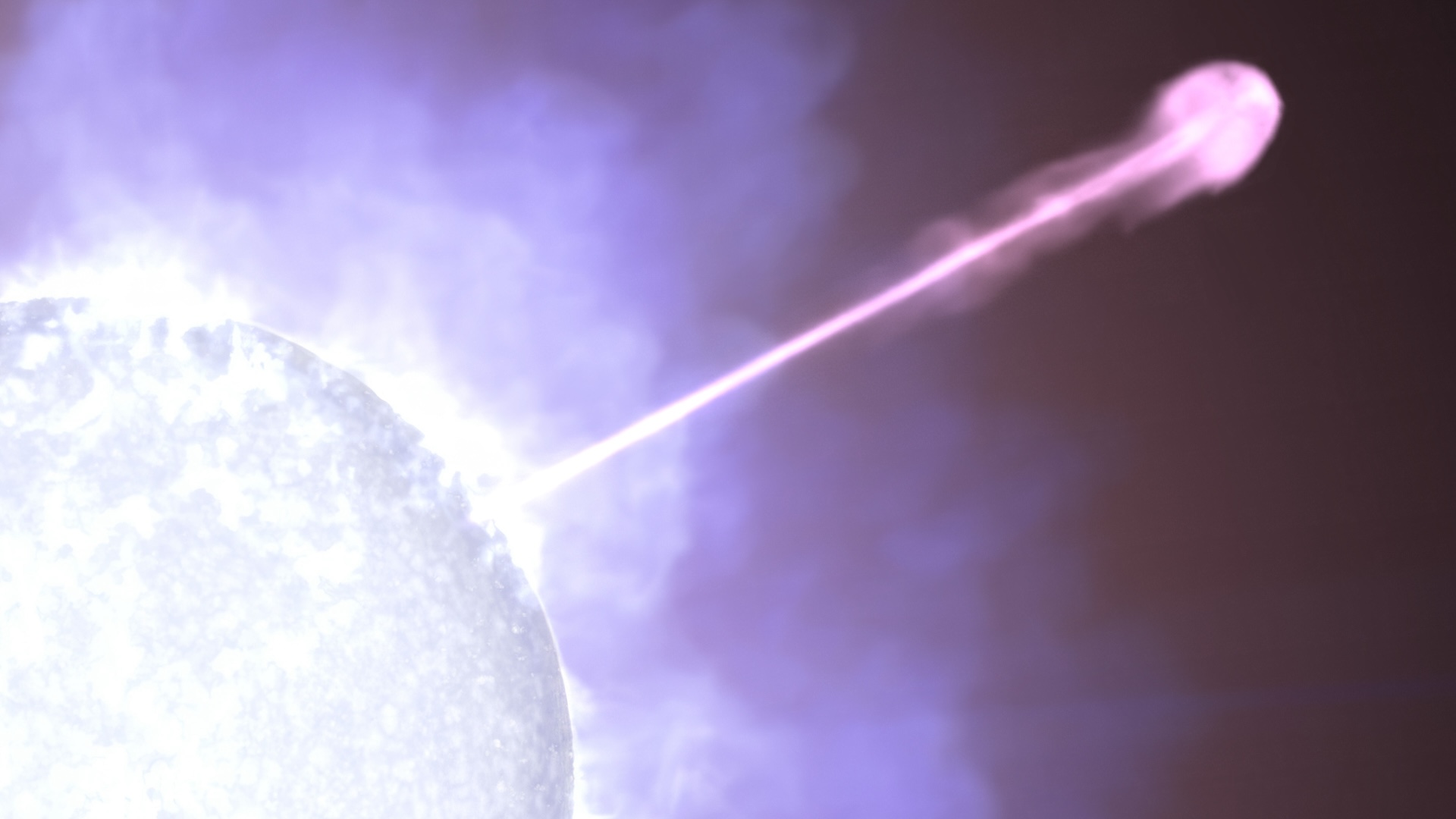

The cosmic explosion was a gamma ray burst (GRB), a massive explosion of gamma-ray light that gets unleashed when a massive star collapses into a black hole. As the resulting cosmic behemoth devours matter, some of that matter is hurled in the opposite direction of the growing black hole, forming powerful jets of energy that beam through the dying star's exterior, according to a statement from NASA.

When those jets aim at Earth, space-based satellites and spacecraft may detect them.

Related: Brightest gamma-ray explosion of all time scrambled Earth's upper atmosphere

The brightest of all-time gamma-ray burst on record — nicknamed the BOAT but officially named GRB 221009A — was detected Oct. 9, 2022. At the time, it beamed so many gamma rays toward our planet that it saturated all the detectors onboard spacecraft circling Earth, including NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

As a result, those detectors blinked out during the most intense part of the explosion. After about five minutes, however, the burst subsided and the detectors began working again. At that point, they detected an unusual peak in energy of around 12 million electron volts, which lasted about 40 seconds, according to the statement. For comparison, visible light has an energy of around 2 to 3 electron volts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When I first saw that signal, it gave me goosebumps," lead researcher Maria Edvige Ravasio, an astrophysicist at Radboud University in the Netherlands and the Brera Observatory, said in the statement. Scientists have been studying GRBs for 50 years, but this is the first time they've detected a signal like this with high confidence, she added.

The strange energy peak, researchers say, is evidence of electrons and their antimatter partners, called positrons, slamming into each other and destroying each other. When these two types of particles annihilate each other, they typically release energy of about half-a-million electron volts. While that's much lower than 12 million electron volts, the researchers have an explanation: The detected jets were traveling at near-light-speed toward Earth, thus squishing the waves together. This "blueshift" pushes the wave toward much higher energy levels, which are at the "bluer" end of the electromagnetic spectrum.

"The odds this feature is just a noise fluctuation are less than one chance in half a billion," study coauthor Om Sharan Salafia, an astrophysicist at National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF)-Brera Observatory in Milan, said in the statement.

The findings could shed light on the chaotic environment inside these jets. Although we've detected them for decades, scientists still don't understand all the processes that occur when they form.

The new findings were described Thursday (July 25) in the journal Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.