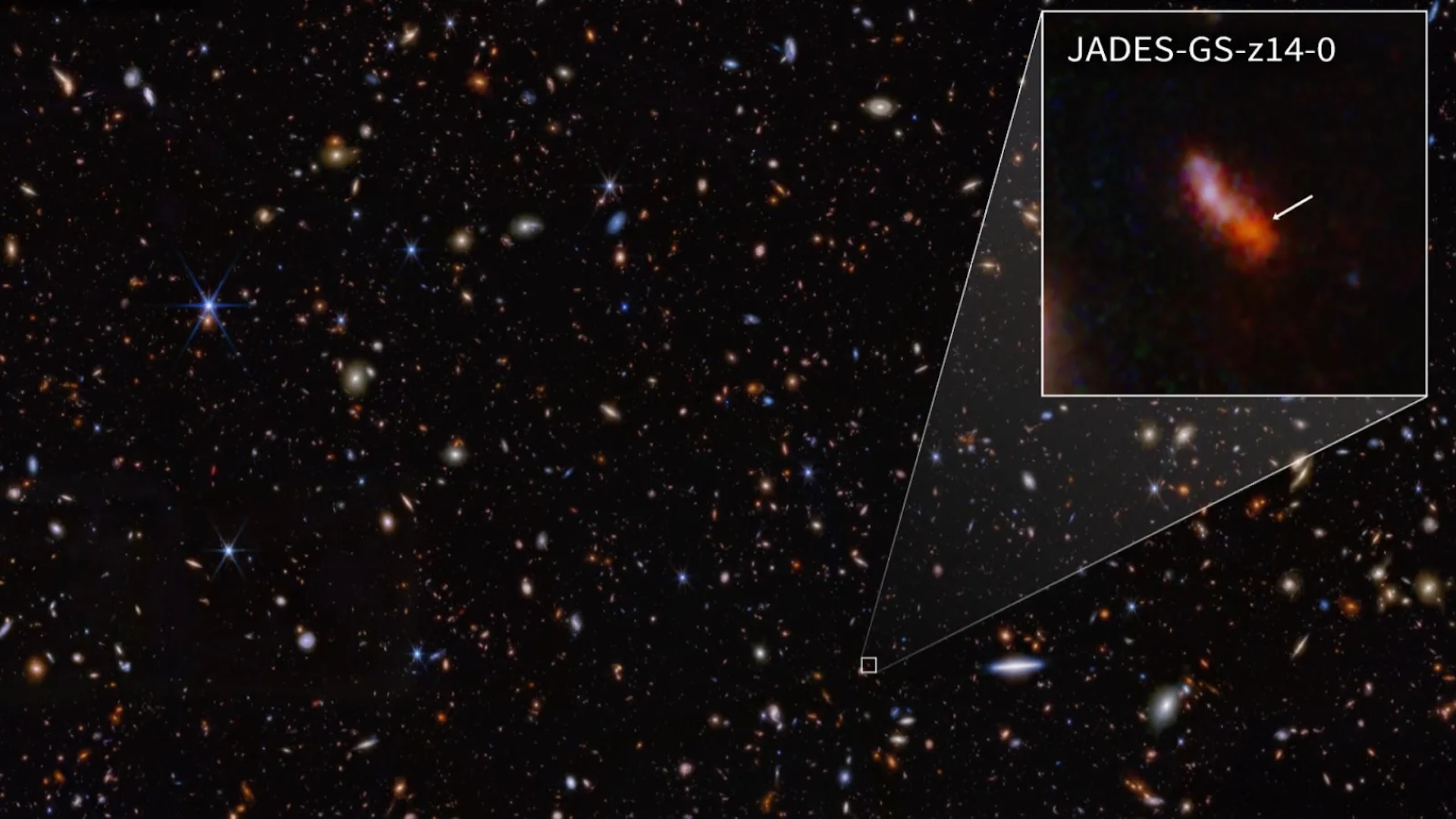

James Webb telescope confirms the earliest galaxy in the universe is bursting with way more stars than we thought possible

The light from the most distant galaxy in the known universe suggests that there's something off about our current cosmological models, a new James Webb Space Telescope study finds. The explanations remain elusive.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has spotted the earliest galaxy ever seen, and its unusually bright light is coming from a bizarre frenzy of star formation.

Named JADES-GS-z14-0, the galaxy formed at least 290 million years after the Big Bang, and contains stars that have been bursting into life since an estimated 200 million years after our universe began.

Spotted by JWST's Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument, the mysterious origins and rapid development of the stars has opened up some fundamental questions about how our universe came to be. The researchers published their findings July 29 in the journal Nature.

"The discovery by JWST of an abundance of luminous galaxies in the very early Universe suggests that galaxies developed rapidly, in apparent tension with many standard models," the researchers wrote in the study. "Galaxy formation models will need to address the existence of such large and luminous galaxies so early in cosmic history."

Astronomers aren't certain when the very first globules of stars began to clump into the galaxies we see today, but cosmologists previously estimated that the process began slowly within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Current theories suggest that halos of dark matter (a mysterious and invisible substance believed to make up 85% of the total matter in the universe) combined with gas to form the first seedlings of galaxies. One billion to 2 billion years into the universe's life, these early protogalaxies reached adolescence, forming into dwarf galaxies that began devouring one another to grow into ones like our own.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But discoveries made by the JWST confounded this view. In February 2023, a group of astronomers analyzing data from the telescope discovered a group of six gargantuan galaxies — aged between 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang — that were so massive they were in tension with 99% of cosmological models.

The light from JADES-GS-z14-0 is similarly puzzling. In the new research, the light detected by NIRSpec finds its origins in an enormous halo of young stars surrounding the galaxy's core, which have been burning for at least 90 million years before the point of its observation. The galaxy is also crammed with unusually high quantities of dust and oxygen, which suggests its history of star birth and death may be even longer.

Interestingly, the researchers wrote, this finding shows that ultra-bright galaxies in the early universe are not just the product of active black holes greedily gobbling up matter, as is often assumed to be the case. The new observations show that runaway star formation is also a viable explanation for the surprising brightness of these ancient galaxies.

So how did galaxies like JADES-GS-z14-0 produce so many stars, so quickly? Answers to this cosmic mystery remain elusive, but it's unlikely they will break our current understanding of cosmology. Instead, astronomers are toying with explanations that include the earlier-than-anticipated appearance of giant black holes; supernova feedback; or even dark energy to understand why these ancient stars were able to form so rapidly.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.