James Webb telescope reveals long-studied baby star is actually 'twins' — and they're throwing identical tantrums

New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope revealed that a distant protostar is actually a pair of baby binary stars that are spitting out parallel energy jets as they gobble up giant disks of gas and dust.

A distant star first spotted decades ago is actually a pair of baby stars that are each spewing powerful energy jets parallel to one another, scientists have discovered.

The unlikely twins were finally identified thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which peered through a dense cloud of cosmic dust to spy the adjacent jets shooting out of the juvenile stars, researchers said.

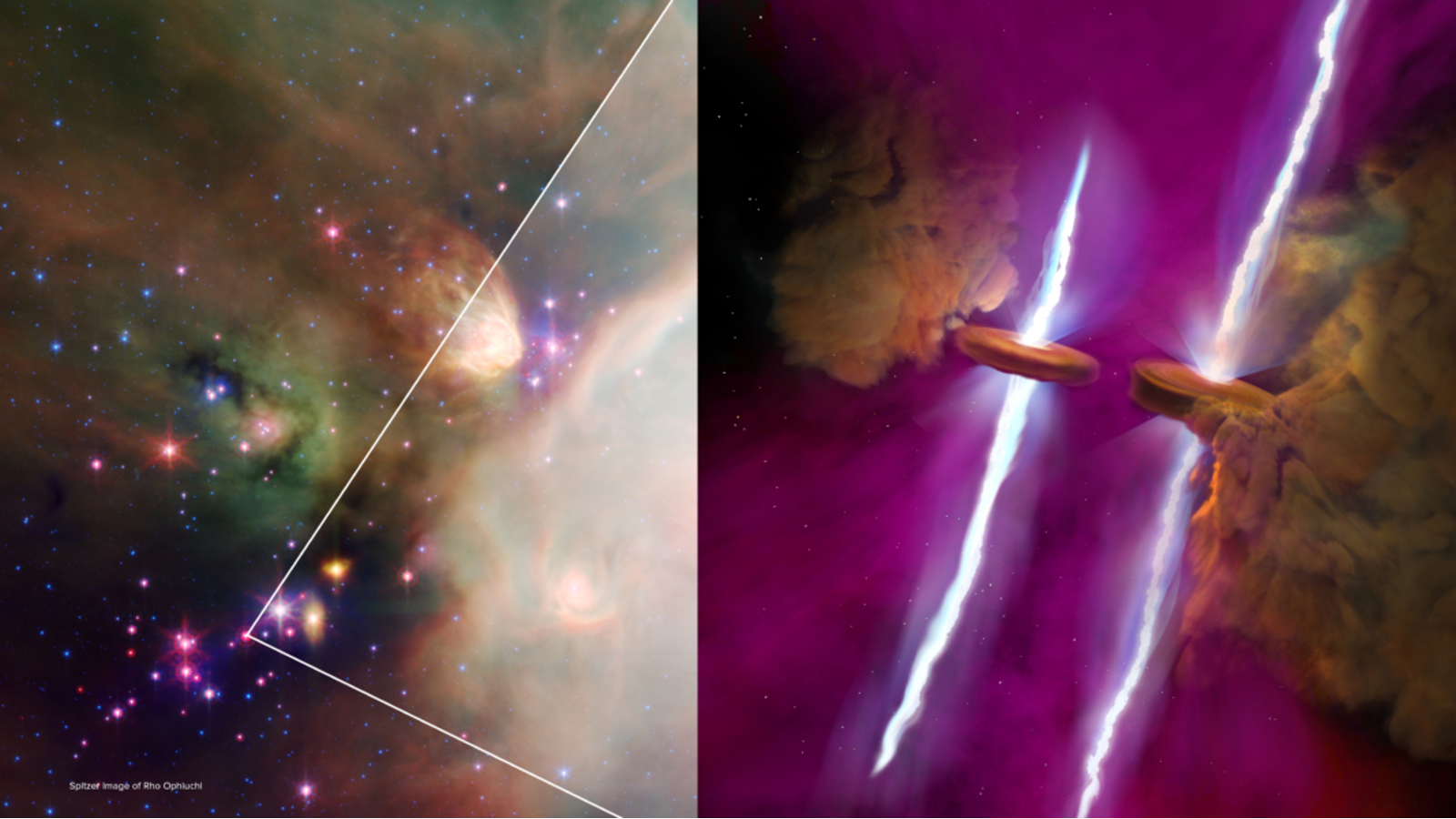

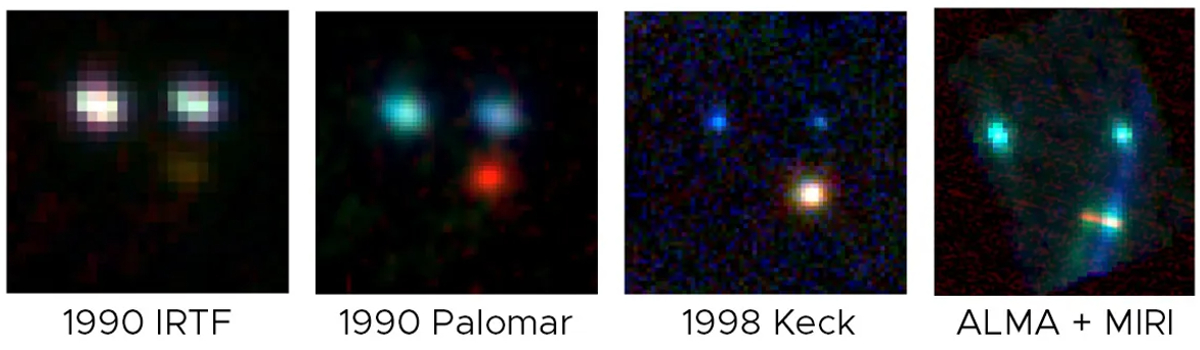

The newly identified stars are located in the WL 20 system — a small stellar cluster in the Rho Ophiuchi cloud complex, about 400 light-years from Earth. Researchers have been studying this system for around 50 years and have listed a number of stars there, including a baby star, or protostar, designated WL 20S, which was surrounded by a large ring of gas and dust, known as a protoplanetary disk.

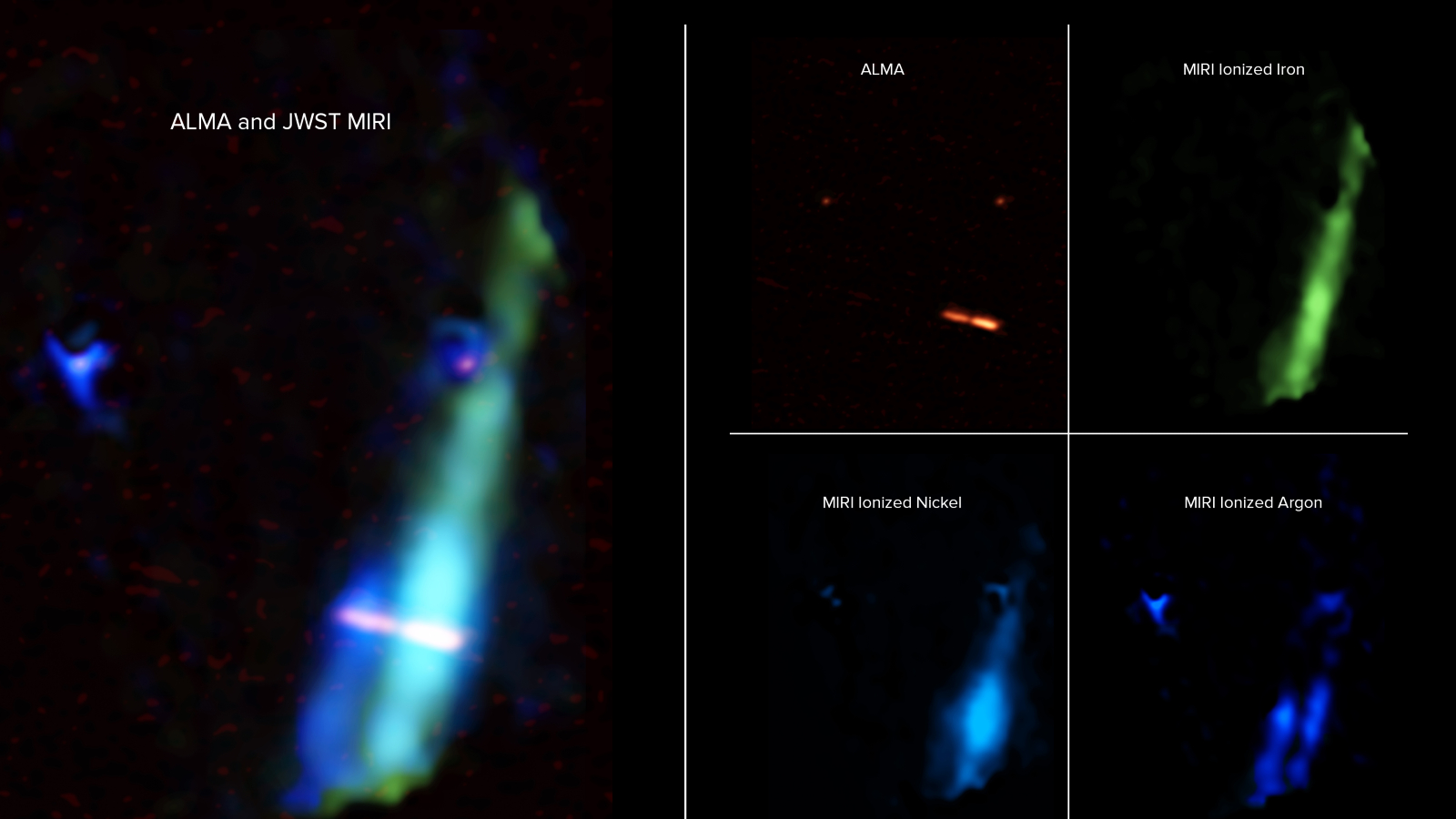

However, recent observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) — a group of more than 60 radio antennas in Chile — hinted that this disk could actually be two separate disks. Follow-up observations from JWST then confirmed this. The space telescope also revealed the presence of stellar jets, which are made up of superheated material ejected by the stars' magnetic poles as they form.

"What we discovered was absolutely wild," Mary Barsony, an astronomer with the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute, said in a statement. "We actually saw that this ONE star was TWO stars right next to each other."

Researchers presented the new findings June 12 at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomy Society.

Related: 8 stunning James Webb Space Telescope discoveries made in 2023

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The two stars, which are yet to be individually named, are binary stars, meaning that they orbit one another. They likely formed from a single protoplanetary disk that fragmented early on in the star formation process, the researchers said.

Based on the size of their respective disks, which are both around 100 times wider than the distance between the sun and Earth, researchers estimate that they are between 2 million and 4 million years old, which is a tiny fraction of our home star's roughly 4.6 billion years in space.

The researchers believe there is a decent chance that exoplanets will eventually form from what's left of the protoplanetary disks when the stars have fully formed.

Despite being studied for decades, astronomers have only collected limited data from the WL 20 cluster due to a large cloud of dust that is located between the far-off region and Earth. This cloud blocks almost all visible light, meaning researchers have to rely on infrared radiation from the stars and their surrounding objects.

Until now, telescopes have not been powerful enough to properly distinguish infrared light at high resolution. But JWST's state-of-the-art Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) enables the space telescope to see more wavelengths of this invisible radiation in greater detail than ever before.

"Without MIRI we would not have known this was two stars or that these jets existed," Barsony said in a NASA statement. The power of MIRI is astonishing, she added. "It's like having brand new eyes."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.