James Webb telescope spots bizarre 'cat tail' flowing out of nearby star, and scientists can't fully explain it

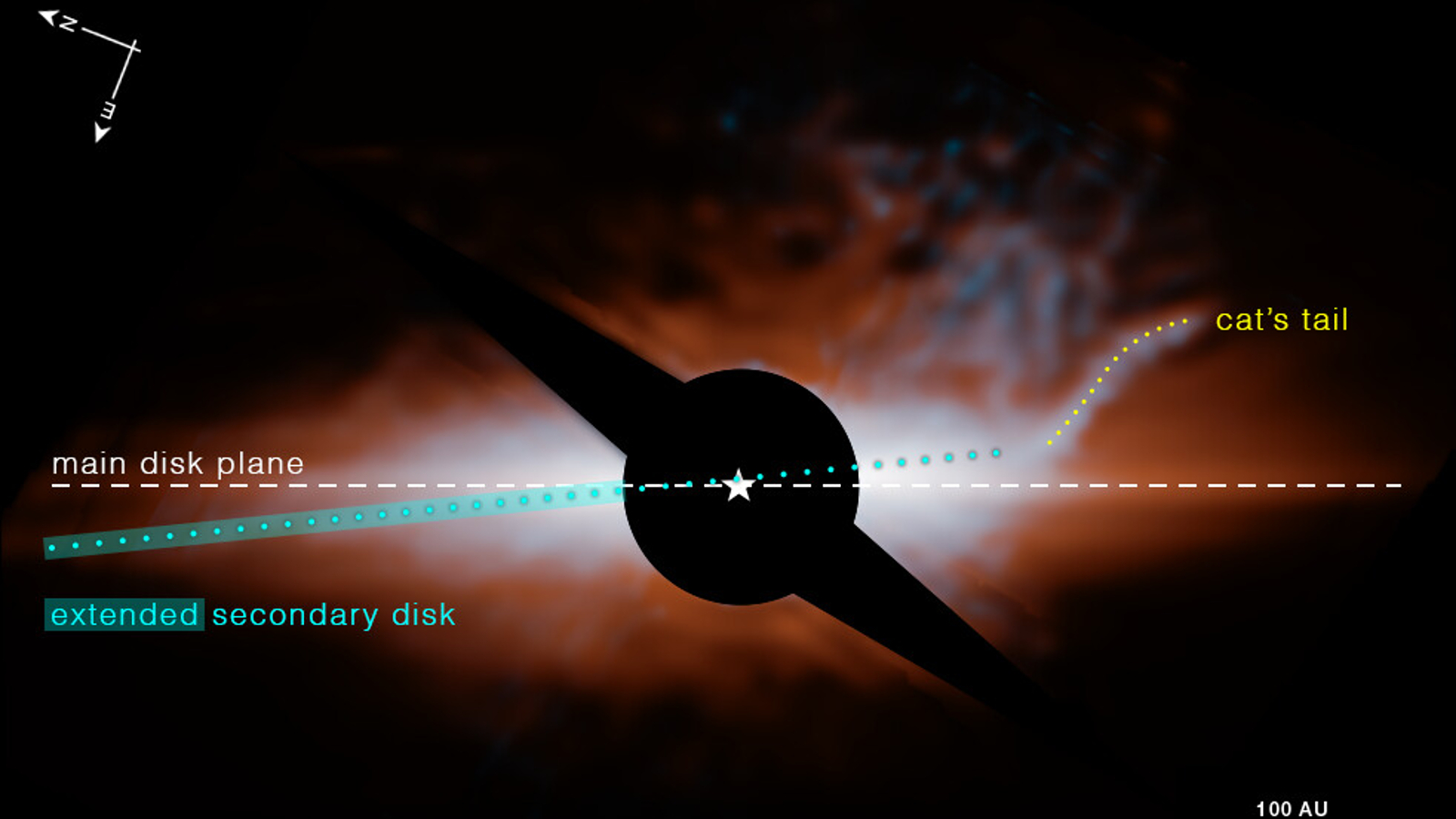

New images from the James Webb Space Telescope have revealed a bizarre string of dust in the shape of a cat's tail around the nearby juvenile star Beta Pictoris.

A newborn star in our cosmic backyard is being circled by an unusual, cat-like tail of gas and dust, new images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) reveal. And the strange structure is proving to be very hard to explain, new research shows.

The star, named Beta Pictoris, is a young, sun-like star located around 63 light-years from the solar system, making it one of our closest neighbors. (The closest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri, is just 4 light-years away, for comparison). It was first discovered in 1984 and has been heavily studied ever since. Past observations have revealed that Beta Pictoris is less than 20 million years old, which is very young for a star.

Like all other infant stars, Beta Pictoris is still surrounded by a large ring of superheated gas and dust, known as a protoplanetary disk. Over time, the dust and gas will cool and begin to stick together, forming planets, moons and asteroids, just like what happened in the solar system. So far, two gigantic exoplanets have been discovered lurking within the nearby star's protoplanetary disk: Beta Pictoris b and Beta Pictoris c, each of which is several times larger than Jupiter.

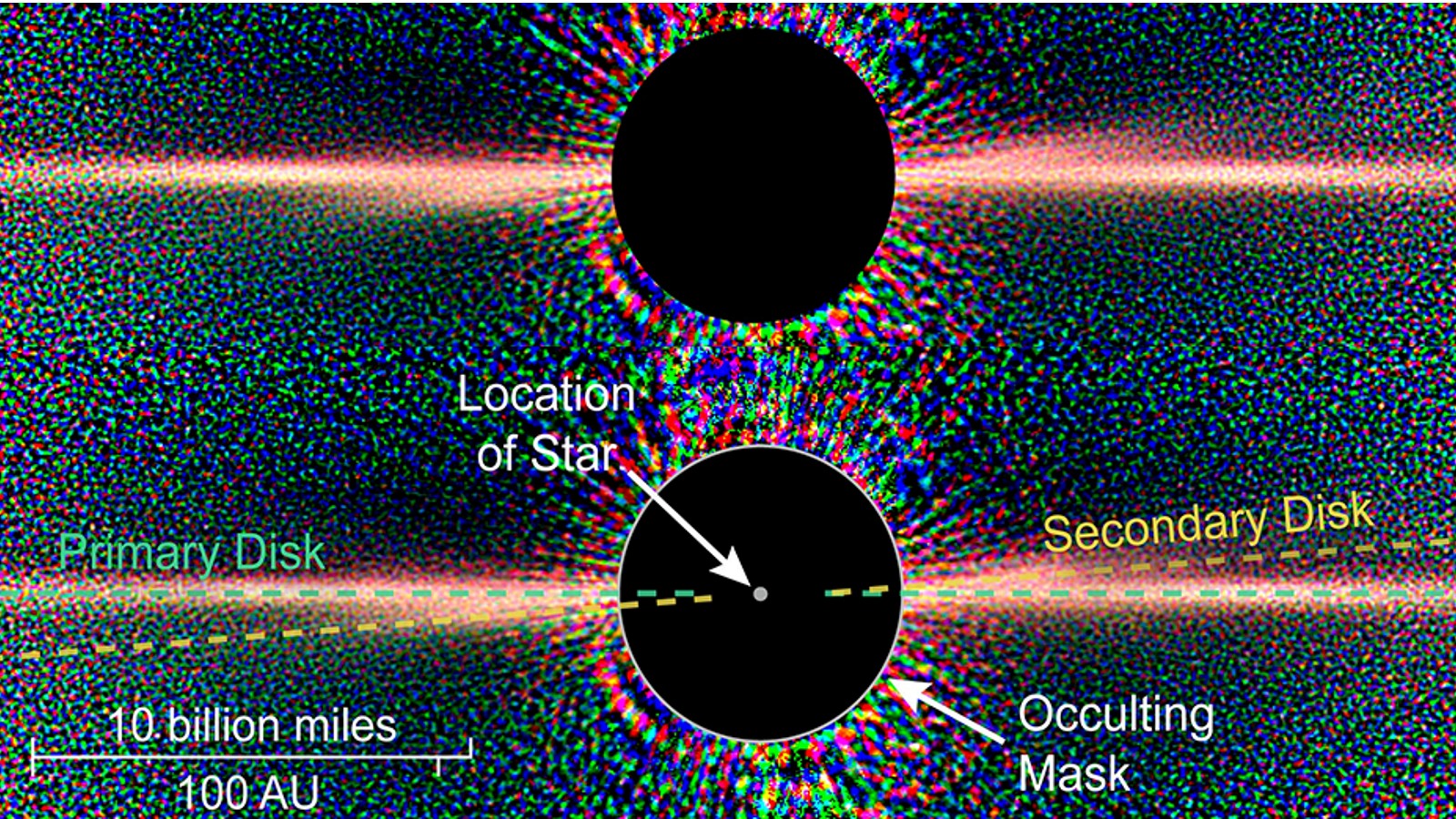

However, in 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope discovered a fainter secondary disk rotating around Beta Pictoris at a slight angle to the main disk. This was one of the first times a secondary disk had ever been seen around a star, according to NASA.

Now, new infrared images captured by JWST have revealed an intriguing new feature in this secondary disk: a string of detached material that bends farther away from the main disk, giving it an appearance similar to a cat's tail. The new findings were presented at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which was held Jan. 7-11 in New Orleans.

"The cat's tail feature is highly unusual," study co-author Christopher Stark, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and a project scientist for JWST, said in a statement. It suggests that the Beta Pictoris system "may be even more active and chaotic than we had previously thought," he added.

Related: James Webb telescope finds water in roiling disk of gas around ultra-hot star for 1st time ever

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The tail is not very dense. Researchers estimate that its mass is equivalent to some of the largest asteroids from our solar system, spread across 10 billion miles (16 billion kilometers).

Although the tail appears to curve steeply away from the rest of the disk, the researchers think this may be an optical illusion created by JWST's skewed viewpoint of the alien star. Instead, they think it veers away from the disk by an angle of only around 5 degrees.

The researchers are not exactly sure what caused the cat's tail to form. Their current best guess is that the tail was birthed from some sort of asteroid-protoplanet collision that sprayed some of the disk's material outward. This displaced material may then have been stretched out and shaped by the star's light.

"The light from the star pushes the smallest, fluffiest dust particles away from the star faster, while the bigger grains do not move as much, creating a long tendril of dust," study co-author Marshall Perrin, a planetary astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in the statement.

If this is what happened, the collision could have occurred as recently as 100 years ago, the researchers wrote.

However, it is "extremely difficult" to recreate the cat's tail using computer models of such an event, Stark said. As a result, more research is needed to prove that this is what happened, he added.

The cat's tail is not the only surprise that turned up in the new JWST data. The telescope also revealed that Beta Pictoris' two disks are different temperatures; the secondary ring is much hotter than the main disk. This means that the secondary disk is probably made up of predominantly dark-hued, organic matter rather than gas, the researchers wrote.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.