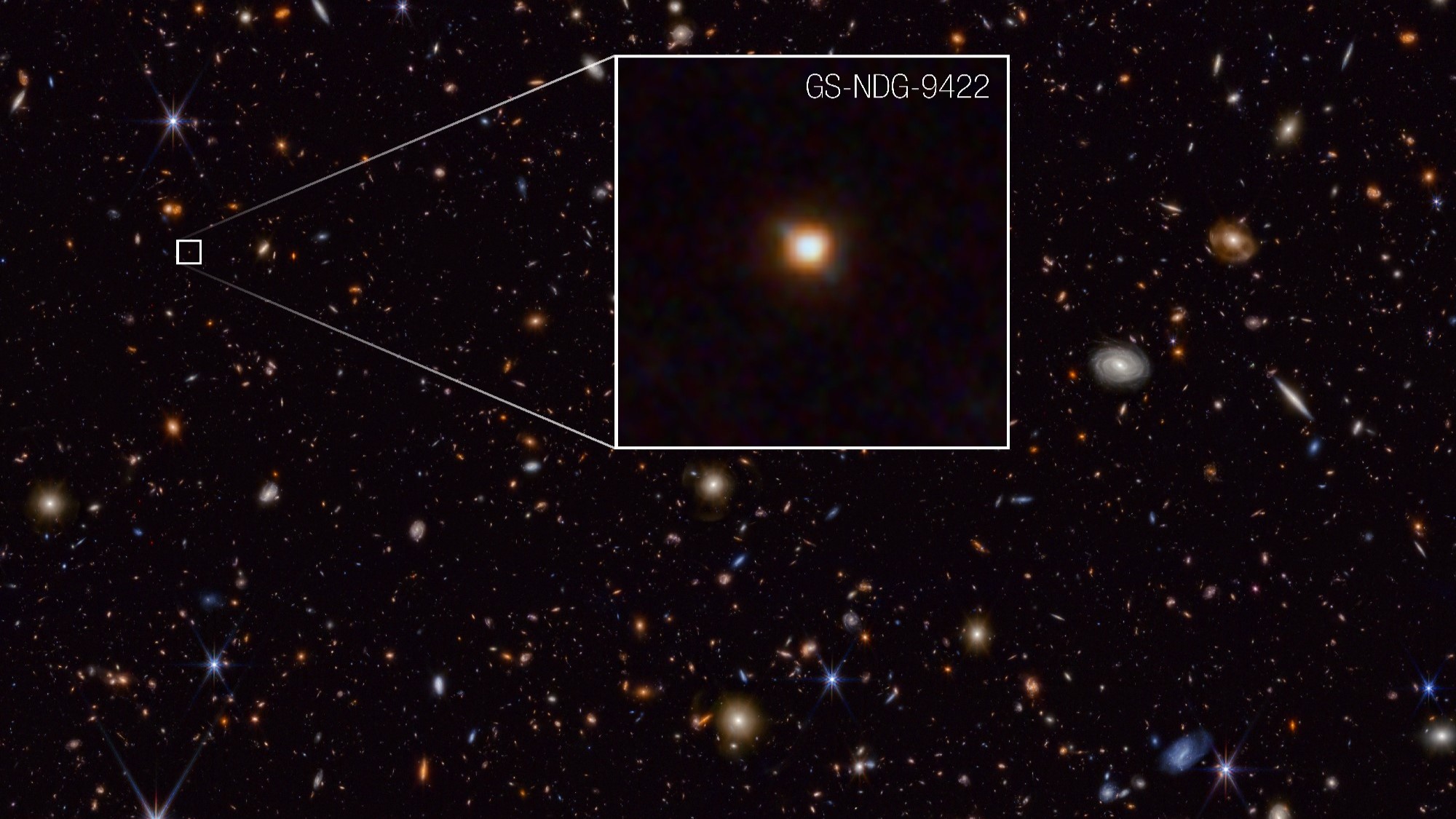

James Webb telescope spots rare 'missing link' galaxy at the dawn of time

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have spotted a rare galaxy at the dawn of time that may be a "missing link" between the oldest generation of stars and the ones we see near Earth.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found a bizarre galaxy in the early universe whose gas outshines its stars, marking it out as a possible missing link in galactic evolution.

The galaxy, called GS-NDG-9422 (9422), was spotted just one billion years after the Big Bang and is filled with massive stars burning nearly twice as hot as those typically found in the local universe.

These exotic stars are bombarding the gas clouds that surround them with enormous quantities of light particles (photons) , heating the clouds up and causing them to outshine the stars they enshroud — a rare trait hypothesized to exist in galaxies that contain the oldest generations of stars, according to the study authors. The researchers published their findings in the October issue of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

"My first thought in looking at the galaxy's spectrum was, 'that's weird,' which is exactly what the Webb telescope was designed to reveal: totally new phenomena in the early universe that will help us understand how the cosmic story began," lead researcher Alex Cameron, an astronomer at the University of Oxford, said in a statement.

Astronomers aren't certain when the very first globules of stars began to clump into the galaxies we see today, but cosmologists previously estimated that the process began slowly during the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Related: James Webb Telescope spots galaxies from the dawn of time that are so massive they 'shouldn't exist'

Astronomers also aren't certain of the types of stars that formed in the early universe, or the time they took to ignite. Yet, as the only material emitted by the Big Bang was hydrogen and helium, the original, primordial stars (dubbed Population III stars) are thought to have been extremely large, very bright and incredibly hot.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But because the first and most massive cosmic furnaces blazed so intensely, they also burned out quickly: exploding in supernovae that scattered heavier elements forged through nuclear fusion in their hearts, thus laying the foundations for planets and later generations of stars.

To search for evidence of the earliest stars, the researchers pointed the JWST at an extremely distant region of the sky. Light travels at a fixed speed through the vacuum of space; this means that the deeper we look into the universe, the further back in time we see as we detect light coming from ever more remote sources.

This fact enabled the astronomers to spot galaxy 9422. The galaxy's stars are burning at temperatures of 140,000 degrees Fahrenheit (80,000 degrees Celsius), almost twice as hot as the 70,000 to 90,000 degrees F(40,000 to 50,000 degrees C) found in our local universe. Despite this, the ultra-hot stars are likely not part of the oldest generation of stars in the universe, as the researchers spotted elements beyond just hydrogen and helium.

"We know that this galaxy does not have Population III stars, because the Webb data shows too much chemical complexity," Harley Katz, a cosmologist at the University of Oxford, said in the statement. "However, its stars are different than what we are familiar with — the exotic stars in this galaxy could be a guide for understanding how galaxies transitioned from primordial stars to the types of galaxies we already know."

With these missing-link stars found, the astronomers are now scouring more of the early universe to add to their population. This will enable them to figure out how common this star type is, providing new clues about the earliest phases of our universe.

"It's a very exciting time, to be able to use the Webb telescope to explore this time in the universe that was once inaccessible," Cameron said. "We are just at the beginning of new discoveries and understanding."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.