NASA spots 'flame-throwing Guitar Nebula' shredding antimatter along a cosmic string

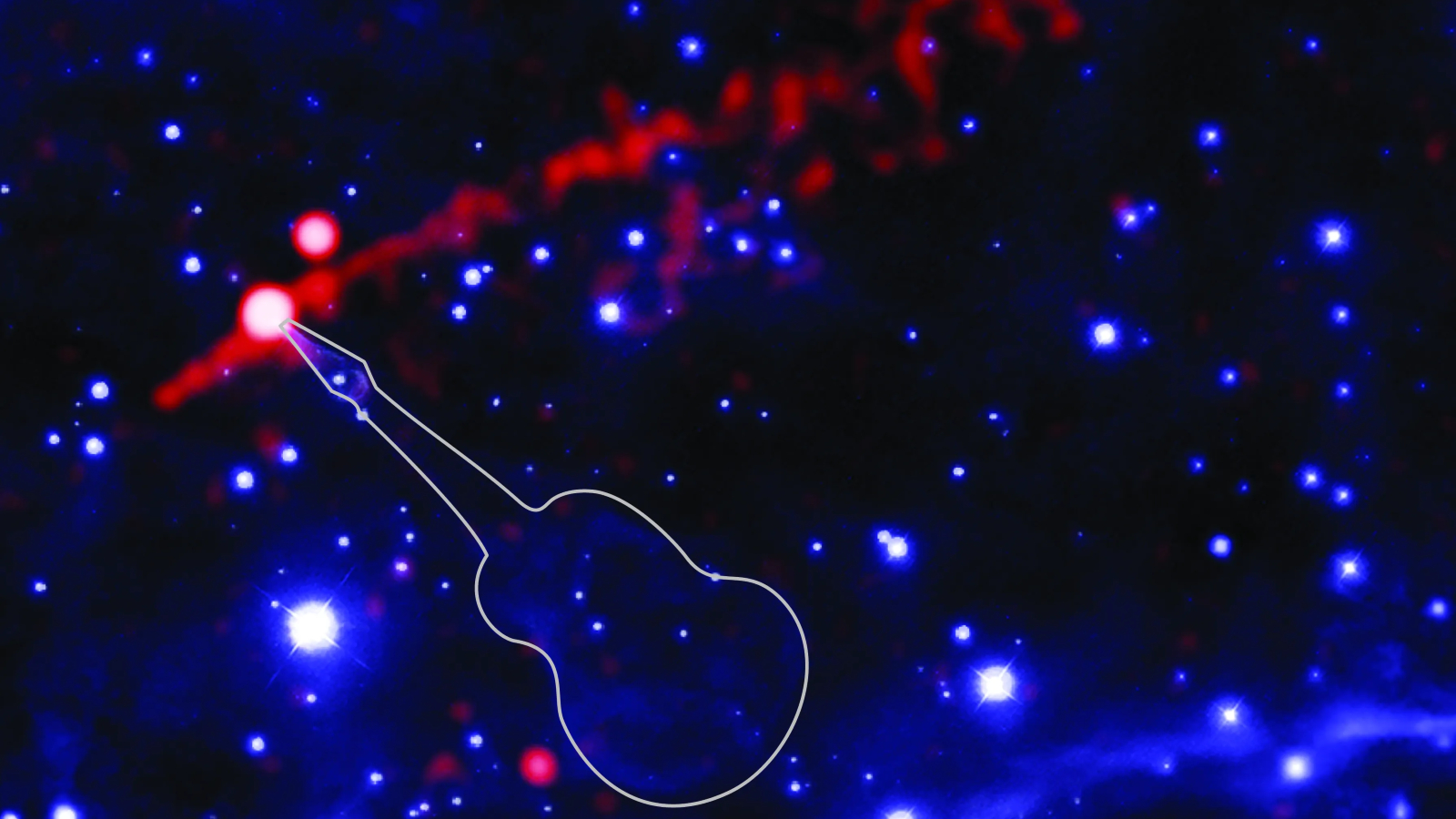

New images show the rapidly rotating pulsar of the "Guitar Nebula" shooting out a gigantic cosmic plume of plasma, X-rays and supercharged particles spinning along a magnetic field line in interstellar space.

Radical new photos show the undead star that formed the "Guitar Nebula" shooting out an epic flamethrower-like jet that is spinning along one of our galaxy's magnetic strings. The cosmic blowtorch, which contains antimatter particles created from pure energy, is helping scientists to learn more about the space in between stars, NASA says.

The Guitar Nebula is a giant cloud of hydrogen gas located around 6,500 light-years from Earth in the Milky Way that formed in the wake of the collapse of the B2224+65a pulsar, a rapidly-spinning neutron star leftover from the collapse of a massive star. The unusually shaped mass is a "bow wave," made up of material blown off B2224+65 by stellar winds as the pulsar moves through space, like the wave created around the front of a boat as it moves through water. From Earth, it looks like a simple acoustic instrument. But in reality, it is a chaotic, shapeless mass flowing behind the dead star.

The nebula was first discovered in 1993. Since then, scientists have determined that the pulsar is rotating at around 3.6 million mph (5.76 km/h). As a result, it is also shooting out a giant flamethrower-like energy jet, around 2 light-years, or 12 trillion miles (19 trillion kilometers) long. The jet shoots out of the pulsar perpendicular to the Guitar Nebula, making it seem like the fiery torrent is emerging from the instrument's head.

The new images, which were released Nov. 20, are composites of observations taken by the Palomar Observatory in California, which shows visible light in blue, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory space telescope, which shows the X-rays given off by the jet in red, according to a NASA statement.

The looped timelapse below shows how the jet has changed shape over time. This mini-video uses multiple images from Chandra, taken in 2000, 2006, 2012, and 2021, superimposed over a single image of the Guitar Nebula. As a result, the nebula appears to stay exactly the same shape. But in reality, it would have morphed over time, just like the jet.

Related: 25 gorgeous nebula photos that capture the beauty of the universe

Pulsar jets are created by a combination of the undead star's rapid spin and intense magnetic fields, which are thousands of times stronger than Earth's magnetic field. This mix of factors accelerates particles and shoots them along the object's magnetic poles, which also generates beams of electromagnetic radiation, mainly in the form of X-rays.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The energy of these jets is so high that some of the radiation gets transformed into matter via Albert Einstein's E=mc2 equation, which famously showed us that matter and energy are two sides of the same coin. When this happens, the energy is transformed into pairs of electrons and positrons — the positively charged antimatter counterparts of electrons.

These particle pairs get blasted out into space and flow along giant magnetic field lines that permeate the interstellar medium — matter and radiation that exists in the space between stars within a galaxy. If they ever collide with one another, then they will destroy one another via a process known as annihilation and turn back into energy.

While the Guitar Nebula and "flamethrower" jet are not directly connected to one another, a 2022 study using data from Chandra and the Hubble Space Telescope, revealed that variations in the interstellar medium that alter the nebula's shape also affect the jet's output. As a result, researchers hope that continuing to study this pulsar will yield new insights into the mysterious medium that permeates throughout our galaxy.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.