Scientists find evidence of 'supernova graveyard' at the bottom of the sea — and possibly on the surface of the moon

After finding the debris of two colliding stars swimming in the ocean, researchers are after more evidence from the lunar soil.

ANAHEIM, Calif. — The wreckage of some of the universe's most violent explosions has crept closer than you might think; in fact, you may have taken a swim in it during your last dip in the ocean.

By analyzing samples from the deep sea, researchers have found a unique variety of radioactive plutonium that appears to be debris from a rare breed of cosmic explosion called a kilonova, which likely detonated near Earth some 10 million years ago. But proving this explosion's existence will require more evidence, and the researchers think they know where to find it: on the surface of the moon.

"We live in a supernova graveyard," Brian Fields, an astronomer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said in a March 17 presentation here at the 2025 American Physical Society Global Physics Summit. "[Supernovas make] tiny specks of rocks that can literally rain upon the Earth. They'll accumulate in the depths of the ocean, and they'll also hang onto the moon."

Fields has theorized about this cosmic rubble since the 1990s. But it wasn't until 2004 that researchers started sifting out supernova remnants from ocean samples. They found traces of a radioactive version of iron that doesn't occur naturally on Earth and can only be explained by a nearby supernova sometime in Earth's recent history.

In the following years, about a dozen more samples from both the ocean and the moon painted a more detailed picture of this explosive history. Fields and his colleagues' refined theories pointed to two separate supernova events that occurred 3 million and 8 million years ago. "This is direct observational evidence that supernovas are radioactivity factories," Fields said.

A cosmic cocktail

The plot thickened in 2021, when researchers discovered an even rarer substance sprinkled in with those same samples: a radioactive isotope of plutonium. This finding required an origin story even more unusual than the violent star deaths that birth supernovas.

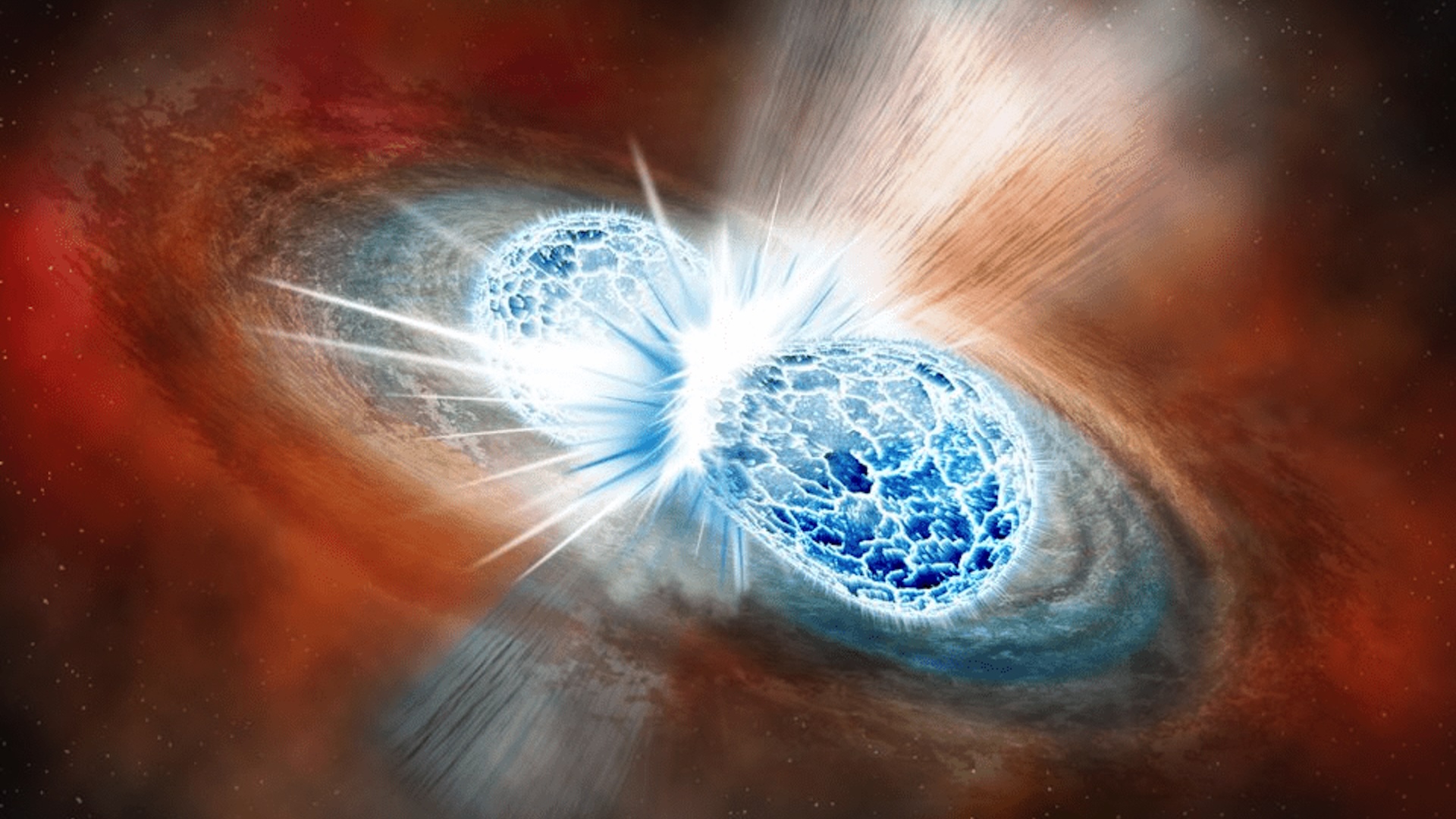

The plutonium variant the researchers found is thought to come from kilonovas — eruptions that occur as two binary neutron stars spiral toward each other in a cataclysmic collision. Kilonovas are also factories for some of our planet's rarest elements, like gold and platinum, and astronomers have long tried to unravel the mechanics of this class of explosion.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: The 10 biggest explosions in history

Now, Fields and his colleagues suspect that a separate kilonova event predated those two previously identified supernovas, erupting at least 10 million years ago. These different explosions formed a sort of radioactive cocktail, embedding a hybrid iron and plutonium signature in the samples.

"We had a kilonova that made plutonium — like it loves to do — and blasted it all over the place," Fields said. "Then, with the stirring of material by a supernova, it got all mixed up, and some of that fell to Earth."

But Fields and his team still want to run more tests to bolster their theory. With renewed efforts like the Artemis missions to return humans to the moon, the researchers are optimistic that the lunar samples they hope to analyze won't be in such short supply.

"Right now, our lunar soil is so precious because it's all we've got," Fields told Live Science. "The hope is, eventually, we'll be taking routine trips to the moon, so it's no big deal — sampling a kilogram won't sound like a lot to people."

With more soil, Fields and his colleagues hope to verify that this kilonova indeed happened, as well as pinpoint when and where it occurred. Because of its simpler geology, the moon should provide a clearer snapshot of exactly how the cosmic debris landed there.

"On Earth, things sink to the bottom of the ocean, and you have to worry about currents and the atmosphere," Fields told Live Science. "But the moon is awesome because when stuff lands, it just lands."

With the next phase of the Artemis mission not set to launch until at least next year, Fields and his team are still a ways away from formally requesting access to this hot commodity. But in the meantime, they're convincing the scientific community that the research is a worthwhile investment.

"We're writing papers to prove to the Artemis community that this is something to seriously think about," Fields said. "The samples are coming back anyway. We just want to piggyback off of it."

Jenna Ahart attended the APS Global Physics Summit through a fellowship from the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing and The Brinson Foundation

Jenna Ahart is a physics and astronomy writer who has previously written for NASA and MIT Technology Review. During her bachelor's at George Washington University, she studied journalism and astrophysics, and she's currently pursuing her master's in science communication at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.