Strange 'slide whistle' fast radio burst picked up by alien-hunting telescope defies explanation

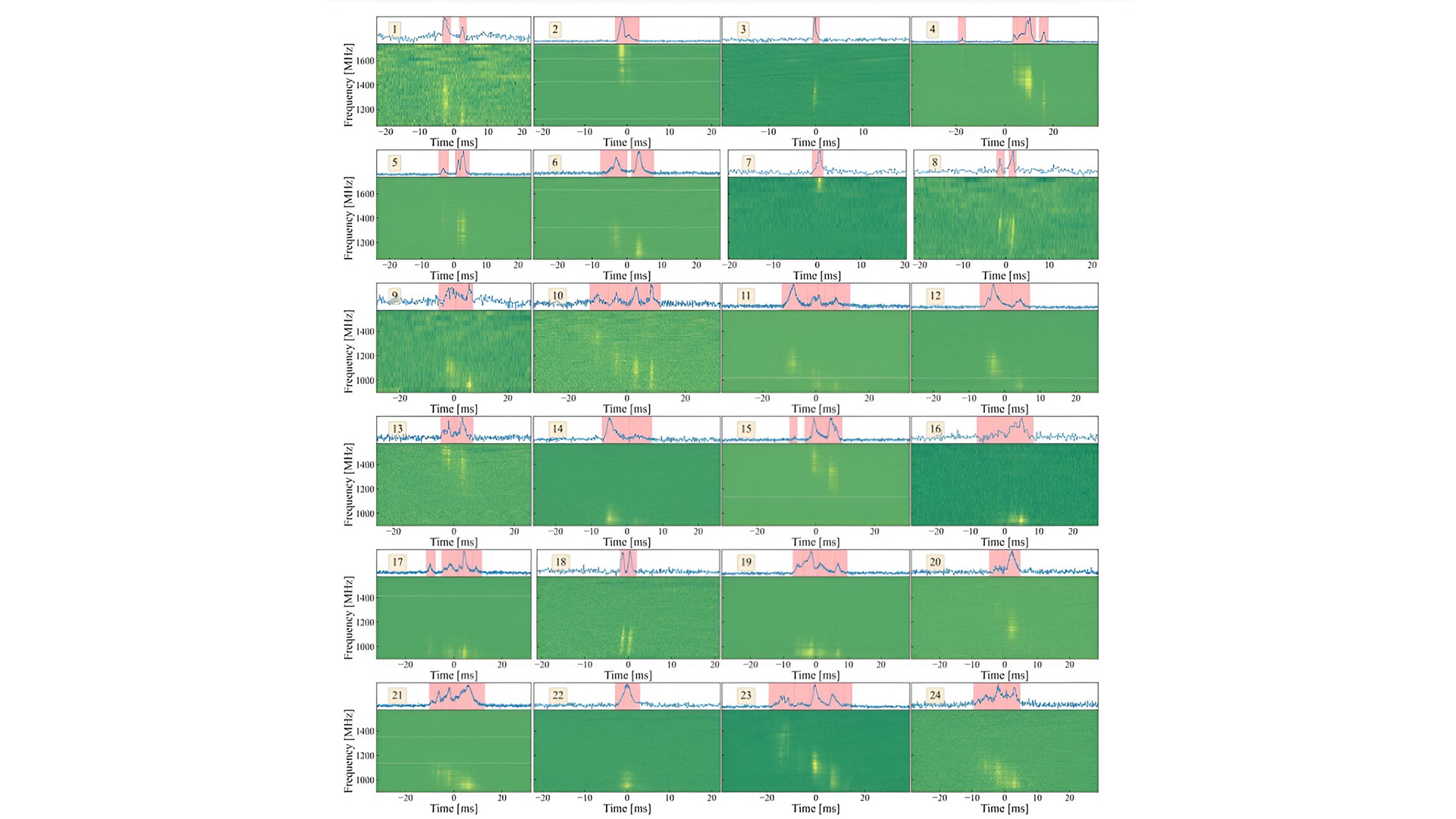

The fascinating patterns of 35 repeating fast radio bursts (FRBs) reveal new properties of these mysterious blasts of deep-space radiation that appear and disappear in milliseconds.

Astronomers watched 35 explosive outbursts from a rare repeating "fast radio burst" (FRB) as it shifted in frequency like a "cosmic slide whistle," blinking in a puzzling pattern never seen before.

FRBs are millisecond-long flashes of light from beyond the Milky Way that are capable of producing as much energy in a few seconds as the sun does in a year. FRBs are believed to come from powerful objects like neutron stars with intense magnetic fields — also called magnetars — or from cataclysmic events like stellar collisions or the collapse of neutron stars to form black holes. Complicating the FRB picture, a few FRBs are "repeaters" that flash from the same spot in the sky more than once, while the majority burst once and then vanish.

The team behind the new research used the SETI Institute's Allen Telescope Array (ATA) to study the highly active repeating FRB known as FRB 20220912A. As they watched the FRB over 541 hours (nearly 23 days), the team saw its bursts of radiation cover a wide range of frequencies in the radio wave region of the electromagnetic spectrum, which eventually developed into a fascinating pattern that astronomers had never seen before.

The new data could finally help unravel the mystery of where deep-space FRBs come from and why a small minority of these rapid and intense blasts of radiation repeat.

Related: Scientists detect fastest-ever fast radio bursts, lasting just 10 millionths of a second

"This work is exciting because it provides both confirmation of known FRB properties and the discovery of some new ones," lead study author Sofia Sheikh, a postdoctoral fellow at the SETI Institute, said in a statement. "We're narrowing down the source of FRBs, for example, to extreme objects such as magnetars, but no existing model can explain all of the properties that have been observed so far."

The findings were accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and a copy is available to read on arXiv.org.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Patterns and chaos in fast radio bursts

Sheikh and colleagues found that the bursts of radiation from FRB 20220912A shifted down in frequency, and when converted to notes played on a xylophone, this shift sounded like a slide whistle's descending toot — a behavior that scientists had never seen before from an FRB. This also helped the team identify that there is a cutoff point for the brightness of bursts from FRB 20220912A, revealing how much of the overall cosmic signal rate this FRB is responsible for.

While there was a noticeable pattern in the frequency of FRB 20220912A's bursts, there was no clear pattern to how long these bursts lasted or how much time passed between them. This shows there is an inherent unpredictability in repeating FRBs.

In addition, the study demonstrated how SETI's ATA — a telescope designed to hunt for radio signals from potential alien intelligence — has an important contribution to make to the study of FRBs and, therefore, some of the universe's most extreme events and objects.

"It has been wonderful to be part of the first FRB study done with the ATA — this work proves that new telescopes with unique capabilities, like the ATA, can provide a new angle on outstanding mysteries in FRB science," Sheikh said.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University