'Totally unexpected' galaxy discovered by James Webb telescope defies our understanding of the early universe

Scientists studying one of the earliest known galaxies using the James Webb Space Telescope have found that the universe's Era of Reionization may have occurred much earlier than previously thought.

An ancient galactic lighthouse is shining through the fog of the early universe, new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations reveal.

Researchers discovered bright ultraviolet (UV) light coming from an ancient, distant galaxy. The findings, published March 26 in the journal Nature, suggest that the universe's first stars modified their surroundings even earlier than expected.

Shortly after the Big Bang, the universe was a soup of protons, neutrons and electrons. As the universe cooled, the protons and neutrons combined to form positively charged hydrogen ions, which then attracted negatively charged electrons to create a fog of neutral hydrogen atoms. This fog absorbed light with short wavelengths, such as UV light, blocking it from reaching farther into the universe.

But as the first stars and galaxies formed, they emitted enough UV light to knock the electrons back off the hydrogen atoms, allowing UV light out once again. Though this "Era of Reionization" is thought to have ended about a billion years after the Big Bang, scientists still aren't sure exactly when the first stars formed — or when the Era of Reionization began.

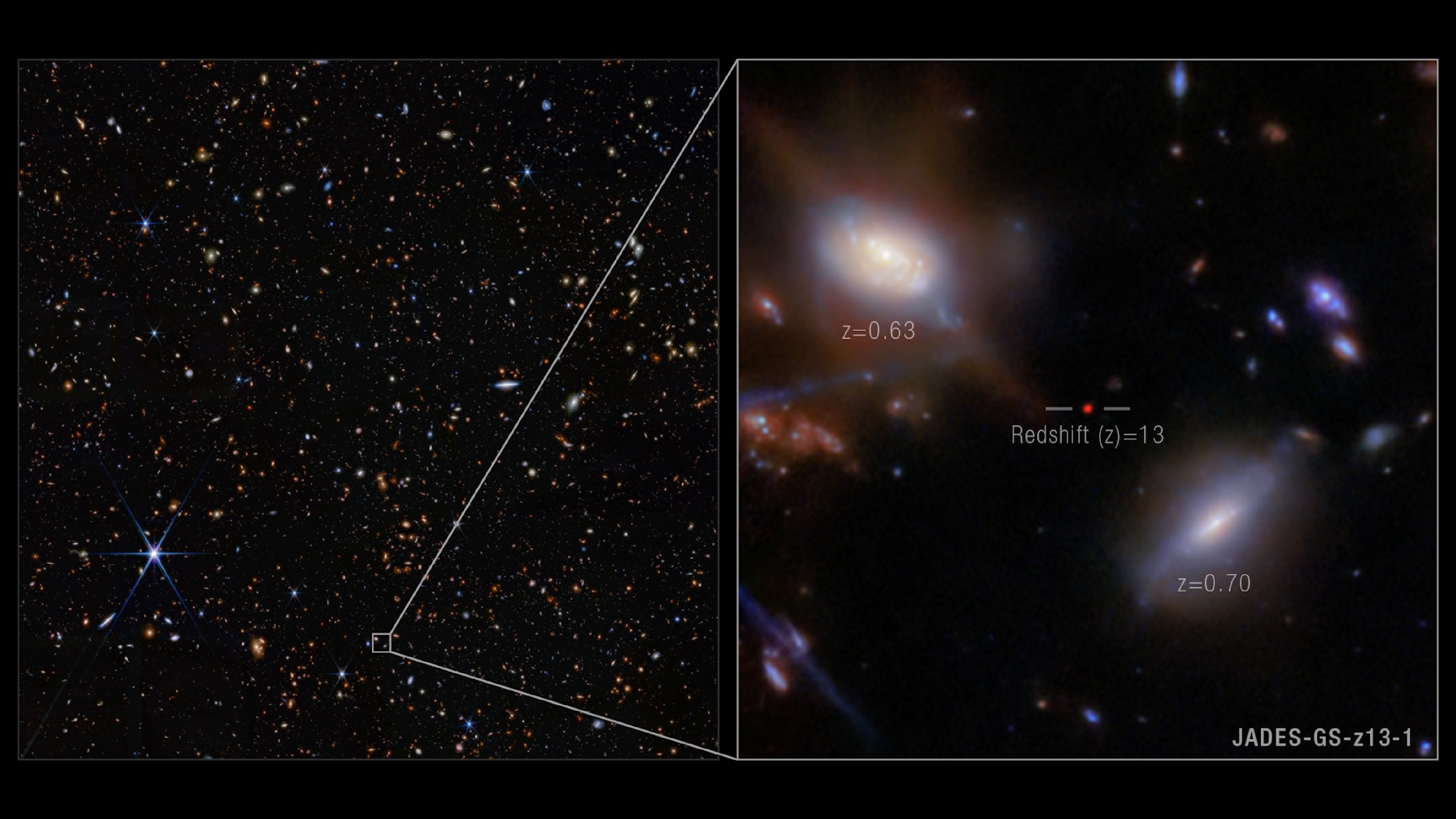

The new findings could help narrow down that starting point. Using JWST, researchers observed an ancient galaxy known as JADES-GS-z13-1. The galaxy is so far from Earth that we're observing it as it appeared just 330 million years after the Big Bang.

In the JWST data, the scientists spotted bright light at a specific wavelength known as the Lyman-alpha emission, which is produced by hydrogen. Though the light started out as ultraviolet, the universe's expansion over more than 13 billion years has stretched it out into the infrared region, making it visible to JWST's sensors.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the Lyman-alpha emission to reach Earth today, JADES-GS-z13-1 must have ionized enough of the hydrogen gas around it to allow the UV light to escape — something scientists hadn't expected so early in the universe's development.

"GS-z13-1 is seen when the universe was only 330 million years old, yet it shows a surprisingly clear, telltale signature of Lyman-alpha emission that can only be seen once the surrounding fog has fully lifted," study co-author Roberto Maiolino, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. "This result was totally unexpected by theories of early galaxy formation and has caught astronomers by surprise."

Researchers still don't know what produced the Lyman-alpha radiation in JADES-GS-z13-1. The light might come from extremely hot and massive early stars, or it might be produced by an early supermassive black hole.

"We really shouldn't have found a galaxy like this, given our understanding of the way the universe has evolved," study co-author Kevin Hainline, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, said in the statement. "We could think of the early universe as shrouded with a thick fog that would make it exceedingly difficult to find even powerful lighthouses peeking through, yet here we see the beam of light from this galaxy piercing the veil."

"This fascinating emission line has huge ramifications for how and when the universe reionized," Hainline concluded.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.