1st detection of 'hiccupping' black hole leads to surprising discovery of 2nd black hole orbiting around it

Scientists found a monster black hole that 'hiccups' every 8.5 days, and a smaller black hole that keeps punching through its accretion disk may be to blame.

Astronomers have spotted the first known instance of a black hole "hiccup," from a distant cosmic behemoth. The cosmic belches suggest the swirling disks of matter and gas that surround black holes may be home to bigger cosmic objects than previously thought.

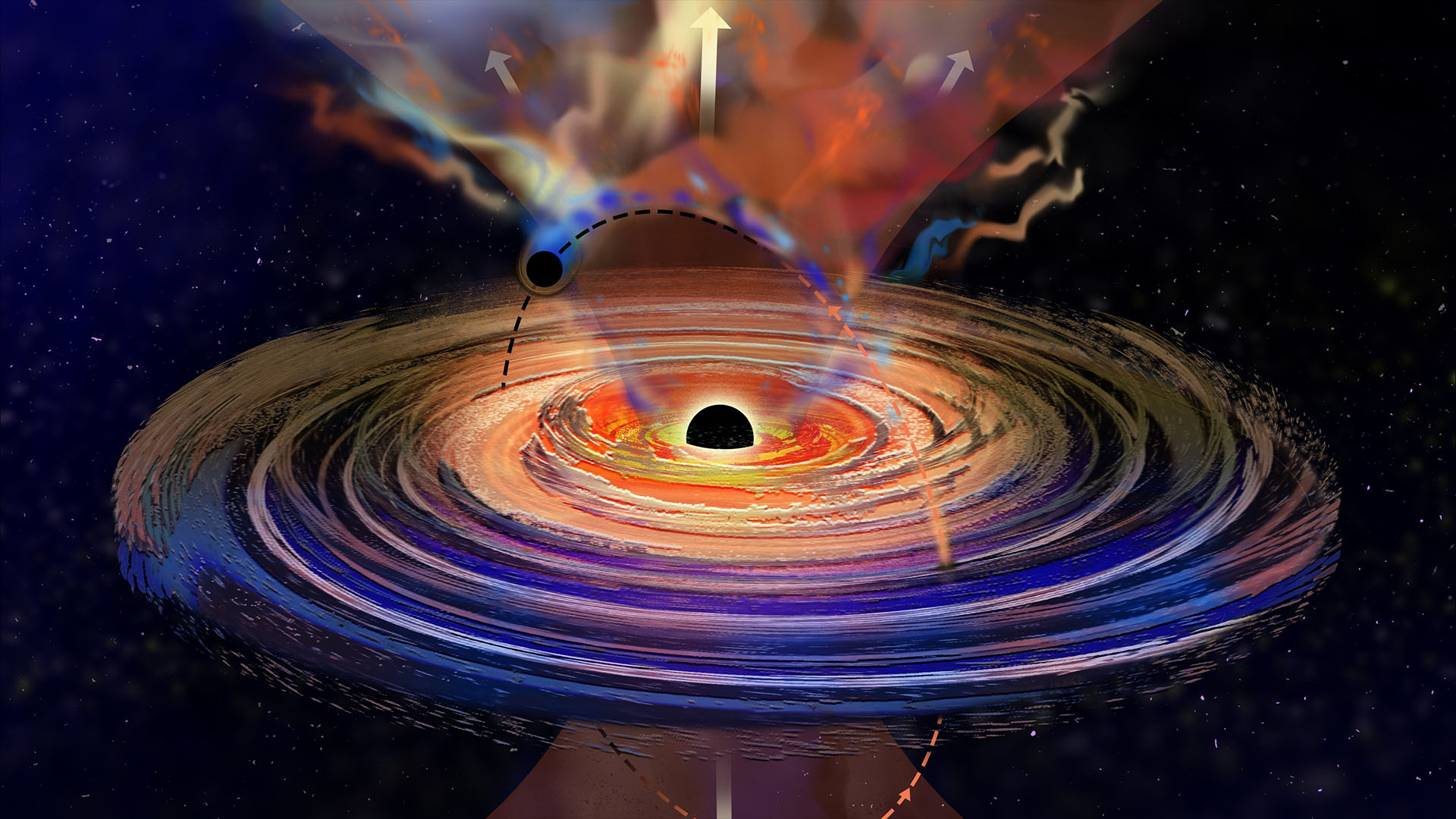

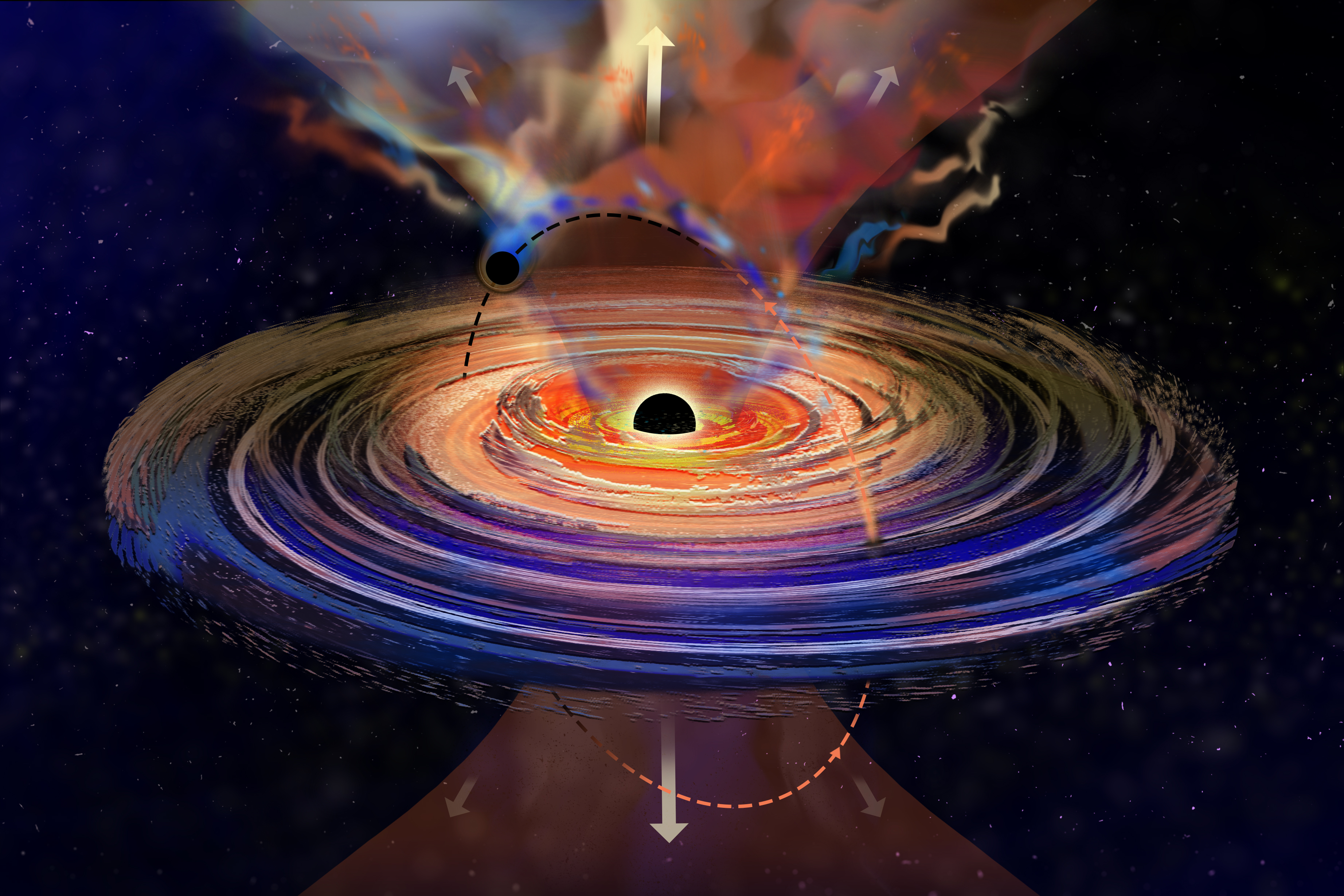

The monster black hole, which weighs the equivalent of about 50 million suns and lives in the heart of a galaxy 800 million light-years from Earth, is ejecting hunks of gas into space once every 8.5 days before going quiet again. These "hiccups" come from the black hole's accretion disk, a ring of superheated gas that swirls around the object.

A new study, published March 27 in the journal Science Advances suggests this material is being belched out thanks to a second, smaller black hole that's swooshing in and out in a tilted orbit, kicking up gas like a fast-flying bee buzzing through a cloud of pollen.

These hiccups "were a total surprise," study lead author Dheeraj Pasham, a research scientist with the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in Massachusetts, told Live Science. "We kept scratching our heads for months until the theorists in the Czech Republic came in and provided an explanation of a secondary black hole, which appears to explain all the properties of this system."

Related: Scientists may finally know where the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe came from

The results suggest the accretion disks around black holes may be home to a surprising array of cosmic objects, including other black holes and stars.

"We thought we knew a lot about black holes, but this is telling us there are a lot more things they can do," Pasham said in a statement. "If our model of a companion repeatedly punching through the accretion disk is right," he told Live Science, "then these hiccups can unveil a whole population of such extreme binaries."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers suspect the immense gravity of the supermassive black hole will someday swallow its companion black hole in a merger, perhaps more than 10,000 years in the future "Because the smaller black hole weighs substantially less than the main black hole, the merger timescale is long," Pasham told Live Science.

A tale of two black holes and an ill-fated star

Astronomers first noticed the monster black hole in December 2020, when telescopes from the All Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae, or ASAS-SN, spotted a prolonged burst of light from its accretion disk. The survey noticed a flash, now named ASASSN-20qc, after it made a small pocket of the sky 1,000 times brighter. The flash persisted for four months and was likely caused by the supermassive black hole shredding a nearby star to pieces.

Follow-up observations with an X-ray telescope aboard the International Space Station (ISS) allowed scientists to catalog subtle, periodic dips in X-ray data from the feasting object, similar to how a planet crossing the face of its host star briefly blocks its light. These were the black hole hiccups.

After discussing the process with colleagues, the researchers determined the black hole hiccuped every time the orbiting secondary black hole punched through the accretion disk, pushing out more material than usual.

While the secondary black hole is the smaller of the two in the system, it is by no means tiny. Scientists estimate it weighs the equivalent of 100 to 10,000 suns, a mass that classifies it as an intermediate black hole. The large difference between the masses of two black holes, differing by a factor of 5,000, makes the newfound duo one of the most extreme mass ratio binaries identified so far.

"This is a different beast," Pasham said in the statement. "It doesn't fit anything that we know about these systems."

In the coming months, the researchers will continue monitoring this system while also studying several other systems that also appear to have the hiccups, Pasham told Live Science. If these black hole binaries also represent extreme mass differences like the newfound duo, then a European Space Agency telescope that just came online, called the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), should be able to detect them. "We anticipate being busy in the next couple of years to model this new population."

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social