Astronomers find black hole's favorite snack: 'The star appears to be living to die another day'

Astronomers have pinned down a faraway black hole's snack schedule after watching it devour a star across years.

Astronomers have succeeded in forecasting the meal timings of a colossal black hole after watching it devour a nearby star in bits and pieces, they announced earlier this week, marking a step forward in understanding the elusive eating behavior of these cosmic voids.

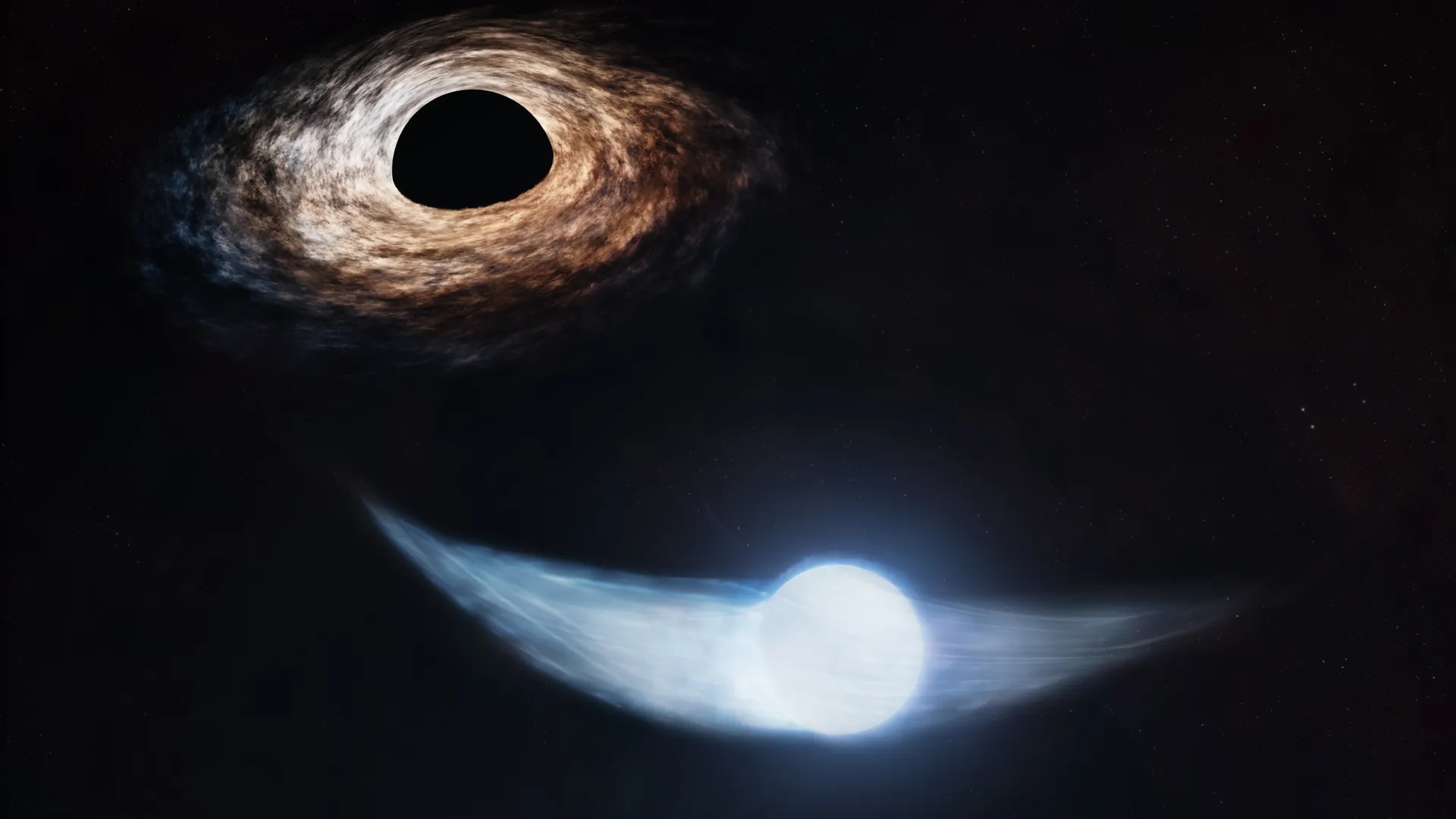

The data behind the forecasts was beamed home in 2018, when an automated ground-based survey flagged a surge in brightness from a galaxy roughly 860 million light-years from Earth. The flare-up — which can be likened to turning on a cosmic light switch billions of times brighter than our sun — pointed to a star being shredded and consumed by a supermassive black hole, which lurks in the center of a faraway galaxy and weighs roughly 50 million times our sun.

The star's decimated material heated up as it approached the black hole, blasting X-ray and ultraviolet emissions strong enough to be picked up by space telescopes. Those signals faded a little over a year later, hinting that the black hole had fully ingested the star. However, the signals appeared to surge once again two years later, showing that the star's core had actually survived the first pass while its outer envelopes were destroyed.

Based on telescope data about the star and its orbit, astronomers used a model to forecast the black hole's second-to-last meal before August 2023. The results were confirmed with follow-up observations taken with the Chandra X-ray telescope, which recorded the predicted drop in bright emissions beaming from the system.

Related: What would happen if a black hole wandered into our solar system?

"Initially we thought this was a garden-variety case of a black hole totally ripping a star apart," Thomas Wevers of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who led the 2023 observations, said in a statement. "Instead, the star appears to be living to die another day."

"The black hole was essentially wiping its mouth and pushing back from the table," Dheeraj Pasham, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who led the latest study, added in the same statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ill-fated star also had a companion star, which was tossed into space at speeds comparable to 1,000 kilometers per second (621 miles per second), study co-author Muryel Guolo of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore explained in the statement. "The doomed star was forced to make a drastic change in companions — from another star to a giant black hole," Guolo said. "Its stellar partner escaped, but it did not."

The star left bound to the black hole ended up being devoured in small portions at a time, which is unlike the conventional "once-and-done" meal of a black hole. It thus offers a new way to probe the physics of black hole behavior, the researchers believe.

"We anticipate that this model will be an essential tool for scientists in identifying these discoveries," study co-author Eric Coughlin, a professor of physics at Syracuse University in New York, said in a university news release.

From recent data collected by Chandra and Swift, the researchers predict the shredded star makes its closest approach to the black hole once every 3.5 years. Its orbit indicates the black hole's third meal — that is, if there's anything left of the star — would kick off between May and August next year. If that feast does occur, it will last for almost two years, Coughlin said.

"This will probably be more of a snack than a full meal because the second meal was smaller than the first, and the star is being whittled away."

A study about these results was published Aug. 14 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Originally published on Space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social