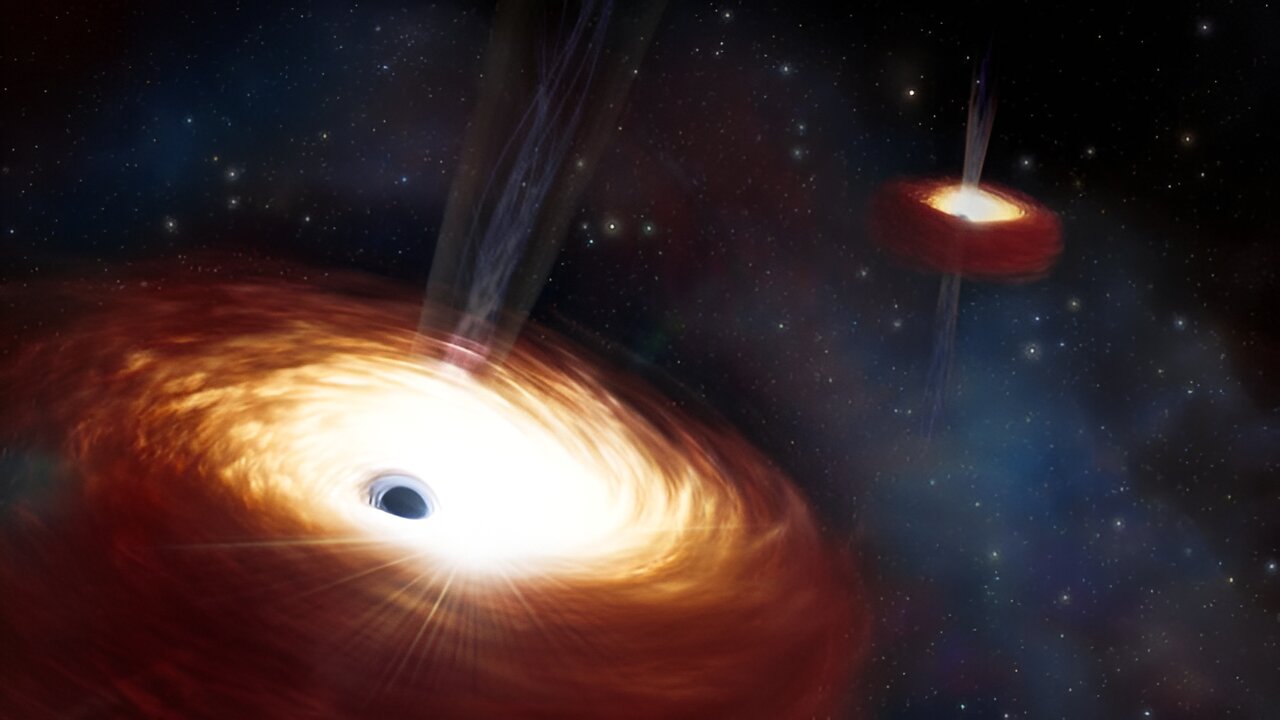

Astronomers find heaviest black hole pair in the universe, and they've been trapped in an endless duel for 3 billion years

Two supermassive black holes spotted circling inside a remote 'fossil' galaxy are the heaviest, and the closest, black hole binary ever found.

Astronomers have spotted the heaviest black hole pair ever seen — a duo weighing the equivalent of 28 billion suns. The black holes' combined mass is so great that they refuse to collide and merge.

The black hole binary, embedded inside the "fossil" galaxy B2 0402+379, consists of two enormous supermassive black holes circling each other at just 24 light-years apart, making them the closest black hole pair ever spotted.

Yet despite their extreme proximity, the twin monsters are locked in orbital limbo: no longer drawing any closer, they have been repeating the same interminable dance for more than 3 billion years. Astronomers are still unsure whether the black hole ballet will continue without intermission or end with a spectacular collision. The researchers reported their findings on Jan. 5 in the Astrophysical Journal.

"Normally it seems that galaxies with lighter black hole pairs have enough stars and mass to drive the two together quickly," co-author Roger Romani, a physics professor at Stanford University, said in a statement. "Since this pair is so heavy it required lots of stars and gas to get the job done. But the binary has scoured the central galaxy of such matter, leaving it stalled."

Black holes are born from the collapse of giant stars and grow by gorging on whatever gets too close — be it gas, dust, stars or other black holes. Yet where the very first black holes came from remains a mystery.

Past simulations of the "cosmic dawn" — the first billion years of the universe— suggest that black holes were born from billowing clouds of cold gas and dust that coalesced into stars so massive they were doomed to rapidly collapse. Once born, these black holes grew larger, trailing growing trains of gas around them that eventually collapsed into the first stars of dwarf galaxies.

Related: Brightest black hole ever discovered devours a sun's-worth of matter every day

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers theorize that as the universe grew, the black holes inside these dwarf galaxies quickly combined with others to seed even larger, supermassive black holes — and with them bigger galaxies.

To find a pair of near-merging black holes, the astronomers scoured archival data collected by the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii. Using the telescope's spectrograph (called GMOS) to break light from stars into distinct colors, the scientists found light that had originated from suns accelerating around the black holes.

This led the astronomers to B2 0402+379 — a "fossil cluster" formed when an entire galaxy cluster worth of stars and gas combined into one gargantuan galaxy.

"The excellent sensitivity of GMOS allowed us to map the stars' increasing velocities as one looks closer to the galaxy's center," Romani said. "With that, we were able to infer the total mass of the black holes residing there."

The black holes inside merging galaxies are thought to combine by entering into orbit around each other and eventually reeling themselves ever closer as their dance dissipates angular momentum by accelerating nearby stars.

Once a pair is close enough, scientists believe that gravitational waves — the thundering distortions of space-time produced by the black holes' pirouettes — carry enough energy away for the dueling monsters to slow and merge.

But scientists have never observed two black holes do this, and the merging of B2 0402+379's black holes has stubbornly stalled for the last 3 billion years — a consequence, the researchers believe, of the gigantic pair being so massive that nothing has been able to slow them.

"We're looking forward to follow-up investigations of B2 0402+379's core where we'll look at how much gas is present," lead-author Tirth Surti, a physics student at Stanford, said in the statement. "This should give us more insight into whether the supermassive black holes can eventually merge or if they will stay stranded as a binary."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.