Astronomers find hundreds of 'hidden' black holes — and there may be billions or even trillions more

Black holes that have been obscured by clouds of dust still emit infrared light, enabling astronomers to spot them for the very first time

Astronomers have discovered hundreds of hidden supermassive black holes lurking in the universe — and there may be billions or even trillions more out there that we still haven't found.

The researchers identified these giant black holes by peering through clouds of dust and gas in infrared light. The finds could help astronomers refine their theories of how galaxies evolve, the researchers say.

Hunting in the dark

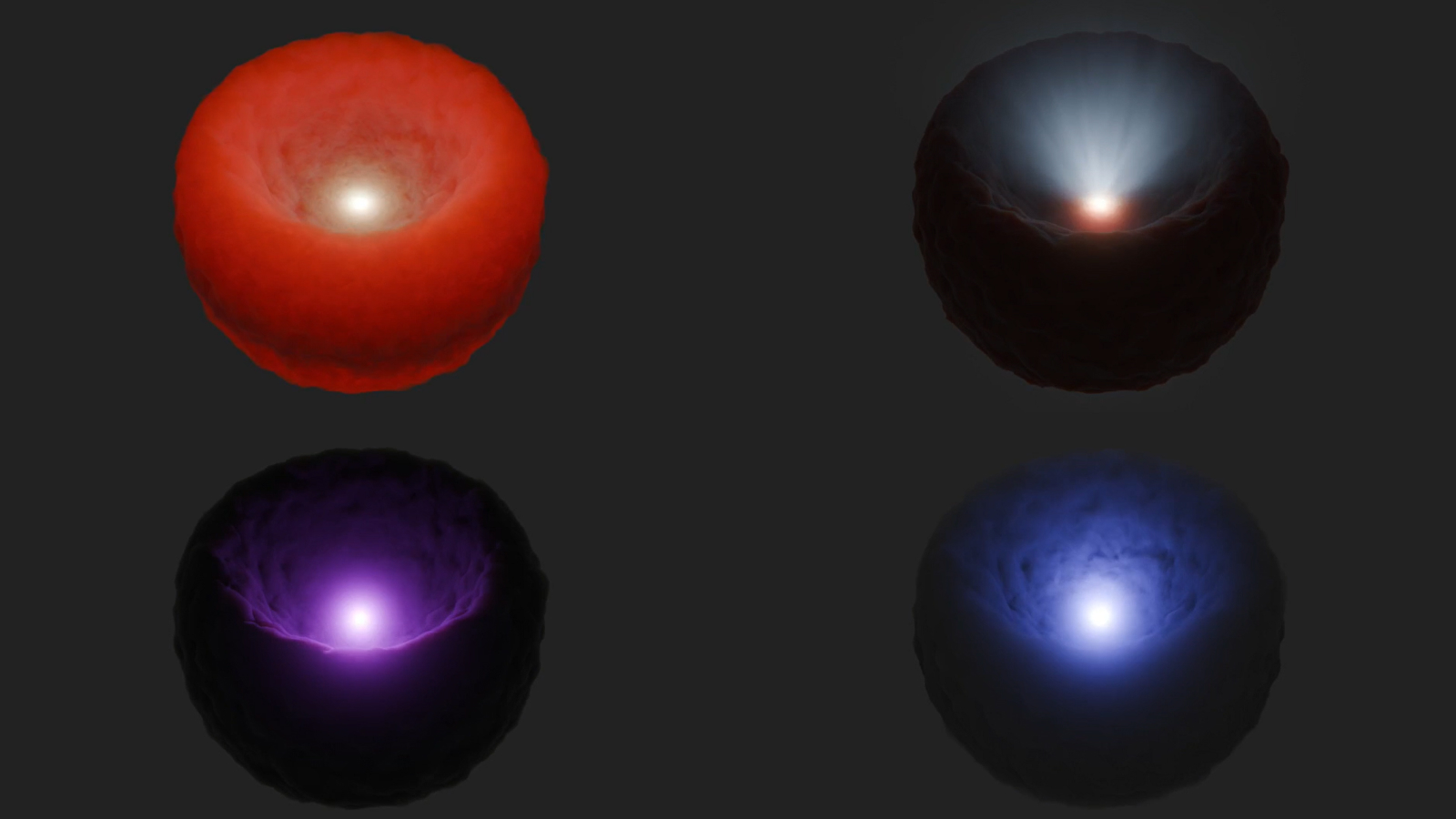

Hunting for black holes is difficult work. They are the darkest objects in the universe, as not even light can escape their gravitational pull. Scientists can sometimes "see" black holes when they devour matter around them; the surrounding material accelerates so fast it starts to glow. But not all black holes have a bright visible ring, so finding them takes a bit more creativity.

Astronomers believe there are billions, or perhaps even trillions, of supermassive black holes — black holes with a mass at least 100,000 times that of our sun — in the universe. One probably lurks at the center of every large galaxy. But it is impossible for scientists to count every single supermassive black hole. Instead, they need to take surveys of nearby galaxies to estimate the number of these black holes hiding in our corner of the cosmos.

There's just one problem: While some black holes are fairly obvious thanks to the bright halo of matter surrounding them, others fly under the radar. This could be because they are obscured by clouds of gas and dust that haven't yet accelerated enough to become incandescent, or because we are viewing them at the wrong angle. A new paper published Dec. 30, 2024 in the Astrophysical Journal estimates that around 35% of supermassive black holes are hidden in this way. This is a dramatic increase from the previous estimate of 15%, though the paper's authors think the true number could be closer to 50%.

Peering through the clouds

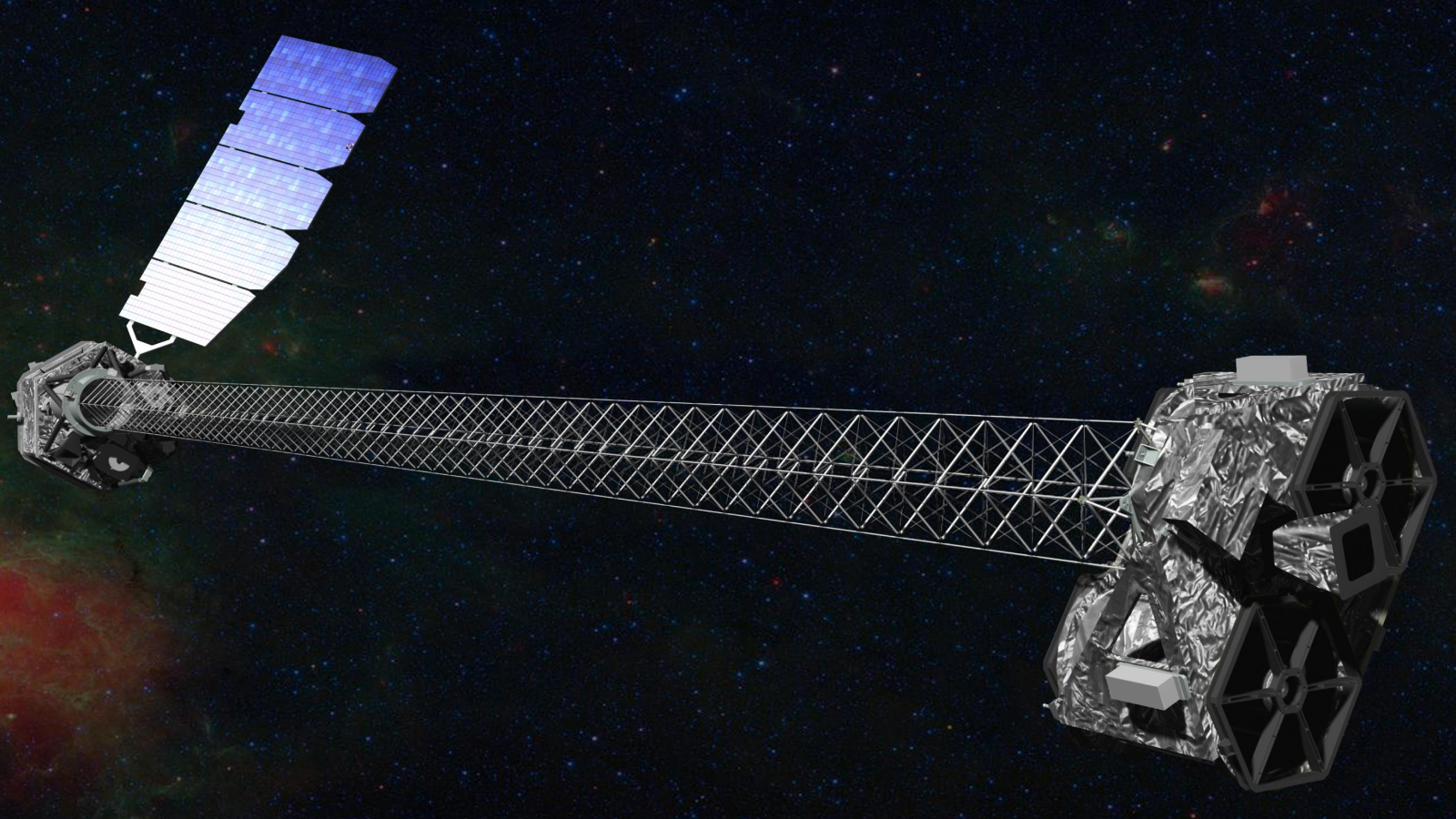

However, astronomers are coming up with ways to locate them. The clouds around obscured black holes still emit some light — just in infrared, rather than in the visible spectrum. In the new study, the researchers used data from two instruments to detect these infrared emissions. The first was NASA's Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), which operated for just 10 months in 1983 and was the first space telescope to peer into the infrared range. The second was the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), a space-based telescope that is run by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, and can detect the high-energy X-rays emitted by the superheated matter swirling around black holes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using archival data from IRAS, the researchers identified hundreds of probable hidden black holes. Then, they used ground-based visible light telescopes and NuSTAR to rule out some candidates and confirm others. A few turned out to be galaxies in the process of forming lots of stars, but many were obscured black holes.

"It amazes me how useful IRAS and NuSTAR were for this project, especially despite IRAS being operational over 40 years ago," study co-author Peter Boorman, an astrophysicist at Caltech, said in a statement.

This technique may help astronomers determine how common supermassive black holes are in the universe, and what role they play in galaxy formation. For instance, these giant tears in space-time may help limit a galaxy's size by drawing it towards a gravitational center or consuming vast quantities of star-forming dust. The technique may even help scientists learn more about the heart of our own Milky Way.

"If we didn't have a supermassive black hole in our Milky Way galaxy, there might be many more stars in the sky," study co-author Poshak Gandhi, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Southampton in the U.K., said in the statement.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.