Black holes can destroy planets — but they can also lead us to thriving alien worlds. Here's how.

Whether a galactic environment has the right conditions for habitable planets to form could depend on how the black hole in that galaxy is rotating.

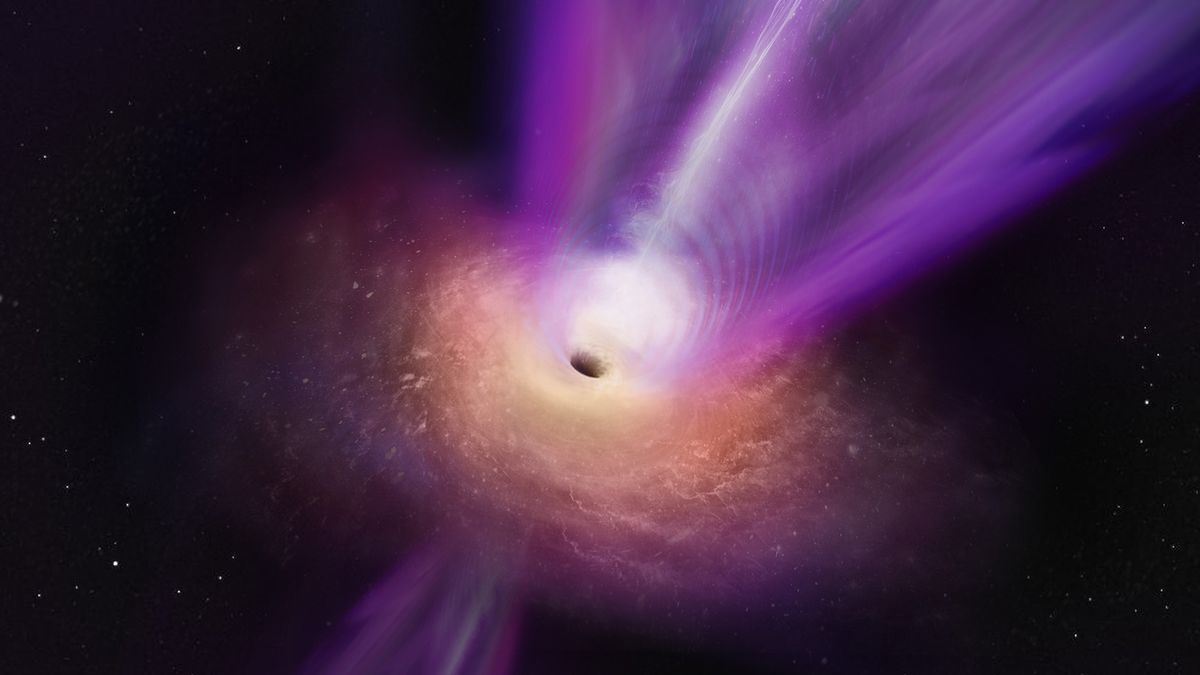

One of the most powerful objects in the universe is a radio quasar — a spinning black hole spraying out highly energetic particles. Come too close to one, and you'd get sucked in by its gravitational pull, or burn up from the intense heat surrounding it. But ironically, studying black holes and their jets can give researchers insight into where potentially habitable worlds might be in the universe.

As an astrophysicist, I've spent two decades modeling how black holes spin, how that creates jets, and how they affect the environment of space around them.

What are black holes?

Black holes are massive, astrophysical objects that use gravity to pull surrounding objects into them. Active black holes have a pancake-shaped structure around them called an accretion disk, which contains hot, electrically charged gas.

Related: 'Very rare' black hole energy jet discovered tearing through a spiral galaxy shaped like our own

The plasma that makes up the accretion disk comes from farther out in the galaxy. When two galaxies collide and merge, gas is funneled into the central region of that merger. Some of that gas ends up getting close to the newly merged black hole and forms the accretion disk.

There is one supermassive black hole at the heart of every massive galaxy.

Black holes and their disks can rotate, and when they do, they drag space and time with them — a concept that's mind-boggling and very hard to grasp conceptually. But black holes are important to study because they produce enormous amounts of energy that can influence galaxies.

How energetic a black hole is depends on different factors, such as the mass of the black hole, whether it rotates rapidly, and whether lots of material falls onto it. Mergers fuel the most energetic black holes, but not all black holes are fed by gas from a merger. In spiral galaxies, for example, less gas tends to fall into the center, and the central black hole tends to have less energy.

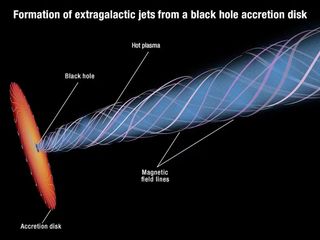

One of the ways they generate energy is through what scientists call "jets" of highly energetic particles. A black hole can pull in magnetic fields and energetic particles surrounding it, and then as the black hole rotates, the magnetic fields twist into a jet that sprays out highly energetic particles.

Magnetic fields twist around the black hole as it rotates to store energy — kind of like when you pull and twist a rubber band. When you release the rubber band, it snaps forward. Similarly, the magnetic fields release their energy by producing these jets.

These jets can speed up or suppress the formation of stars in a galaxy, depending on how the energy is released into the black hole's host galaxy.

Rotating black holes

Some black holes, however, rotate in a different direction than the accretion disk around them. This phenomenon is called counterrotation, and some studies my colleagues and I have conducted suggest that it's a key feature governing the behavior of one of the most powerful kinds of objects in the universe: the radio quasar.

Radio quasars are the subclass of black holes that produce the most powerful energy and jets.

You can imagine the black hole as a rotating sphere, and the accretion disk as a disk with a hole in the center. The black hole sits in that center hole and rotates one way, while the accretion disk rotates the other way.

This counterrotation forces the black hole to spin down and eventually up again in the other direction, called corotation. Imagine a basketball that spins one way, but you keep tapping it to rotate in the other. The tapping will spin the basketball down. If you continue to tap in the opposite direction, it will eventually spin up and rotate in the other direction. The accretion disk does the same thing.

Since the jets tap into the black hole's rotational energy, they are powerful only when the black hole is spinning rapidly. The change from counterrotation to corotation takes at least 100 million years. Many initially counterrotating black holes take billions of years to become rapidly spinning corotating black holes.

So, these black holes would produce powerful jets both early and later in their lifetimes, with an interlude in the middle where the jets are either weak or nonexistent.

When the black hole spins in counterrotation with respect to its accretion disk, that motion produces strong jets that push molecules in the surrounding gas close together, which leads to the formation of stars.

But later, in corotation, the jet tilts. This tilt makes it so that the jet impinges directly on the gas, heating it up and inhibiting star formation. In addition to that, the jet also sprays X-rays across the galaxy. Cosmic X-rays are bad for life because they can harm organic tissue.

For life to thrive, it most likely needs a planet with a habitable ecosystem, and clouds of hot gas saturated with X-rays don't contain such planets. So, astronomers can instead look for galaxies without a tilted jet coming from its black hole. This idea is key to understanding where intelligence could potentially have emerged and matured in the universe.

Black holes as a guide

By early 2022, I had built a black hole model to use as a guide. It could point out environments with the right kind of black holes to produce the greatest number of planets without spraying them with X-rays. Life in such environments could emerge to its full potential.

Where are such conditions present? The answer is low-density environments where galaxies had merged about 11 billion years ago.

These environments had black holes whose powerful jets enhanced the rate of star formation, but they never experienced a bout of tilted jets in corotation. In short, my model suggested that theoretically, the most advanced extraterrestrial civilization would have likely emerged on the cosmic scene far away and billions of years ago.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Black hole quiz: How supermassive is your knowledge of the universe?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.