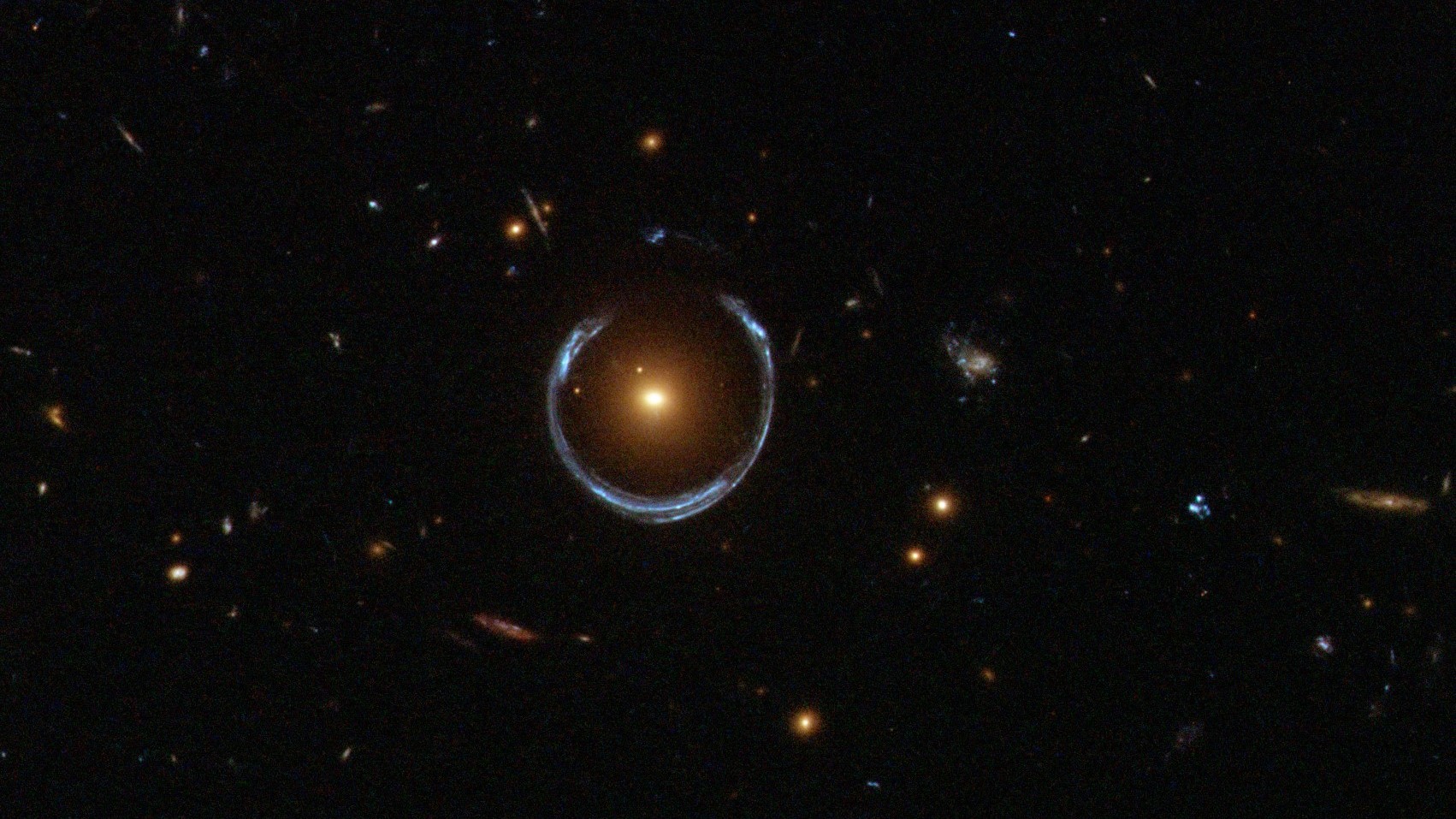

'Cosmic Horseshoe' may contain black hole the size of 36 billion suns — one of the largest ever detected

The "Cosmic Horseshoe" is an Einstein ring, a system made up of a foreground galaxy whose mass is so great, it warps the light from a galaxy behind it. Now, astronomers know where it gets this mass from.

Astronomers have discovered an enormous black hole the size of 36 billion suns lurking within the "Cosmic Horseshoe." The behemoth object is one of the largest black holes ever detected.

First discovered in 2007, the Cosmic Horseshoe is a system of two galaxies located in the constellation Leo. Images of the system show a halo of light surrounding the foreground galaxy, LRG 3-757. This phenomenon, known as an Einstein ring, occurs when the significant mass of the galaxy warps and magnifies light from an even more distant galaxy behind it.

This type of magnification is called gravitational lensing and was first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1915. Now, new research has revealed just how LRG 3-757 gets the mass required to bend light: from a monstrous ultramassive black hole sitting in its center. The researchers published their findings Feb. 19 on the preprint server arXiv, so they have not been peer-reviewed yet.

Einstein's theory of general relativity describes the way massive objects warp the fabric of the universe, called space-time. Gravity, Einstein discovered, isn't produced by an unseen force but by space-time curving and distorting in the presence of matter and energy.

This curved space, in turn, sets the rules for how energy and matter move. Even though light travels in a straight line, light traveling through a highly curved region of space-time, such as the area around a massive galaxy, also travels in a curve — bending around the galaxy and splaying out into a halo.

Related: Mysterious 'Green Monster' lurking in James Webb photo of supernova remnant is finally explained

To find evidence for the black hole lurking within the Cosmic Horseshoe, the astronomers used data collected from the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer spectrograph in Chile's Atacama Desert, alongside images gathered by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By analyzing the powerful gravitational lensing by LRG 3-757 — a galaxy with 100 times the mass of the Milky Way — alongside the speed and manner at which stars move around it, the researchers concluded that the presence of an ultramassive black hole "is necessary to fit both datasets simultaneously."

This detection puts LRG 3-757’s black hole among the largest to ever exist. The biggest, called Ton 618, is estimated to weigh in at 66 billion times the mass of our sun and stretch up to 40 times the distance between Neptune and the sun. Meanwhile, the black hole at the centre of the Holm 15A galaxy cluster is 44 billion solar masses and spans up to 30 times the Neptune to sun distance.

An ultramassive mystery

Astronomers haven't yet explored exactly how LRG 3-757's giant black hole formed. But the stars moving around it are relatively slow, and their movements are less random than would be expected for a black hole of its size.

This could be because some of the stars near it were ejected by past galaxy mergers, or because the black hole once had powerful jets that quenched star formation. Or perhaps the black hole quickly gobbled up many of its surrounding stars earlier in its life.

The astronomers expect to find some of the answers to these questions from the Euclid space telescope, which is one year into its six-year mission to catalog a third of the entire night sky by capturing thousands of wide-angle images. All told, Euclid will capture light from more than a billion galaxies that are up to 10 billion years old, according to the European Space Agency.

Once this is done, astronomers will use Euclid's images to create two maps: one composed of many other Einstein rings, and the other showing shock waves called baryon acoustic oscillations. These maps should help researchers trace dark matter and dark energy — mysterious components of the universe believed to make up most of its matter and cause its accelerating expansion, respectively.

"The Euclid mission is expected to discover hundreds of thousands of lenses over the next five years," the authors wrote in the study. "This new era of discovery promises to deepen our understanding of galaxy evolution and the interplay between baryonic [regular matter] and [dark matter] components."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.