Supermassive black hole spotted 12.9 billion light-years from Earth — and it's shooting a beam of energy right at us

The newly discovered "blazar," which has a mass equal to 700 million suns, is the oldest of its kind ever seen and changes what we know about the early universe.

Astronomers have discovered a supermassive black hole that's shooting a giant energy beam directly at Earth. The cosmic juggernaut, which is about as massive as 700 million suns, is taking aim at us from a galaxy in the early universe, up to 800 million years after the Big Bang — making this the most distant "blazar" ever found.

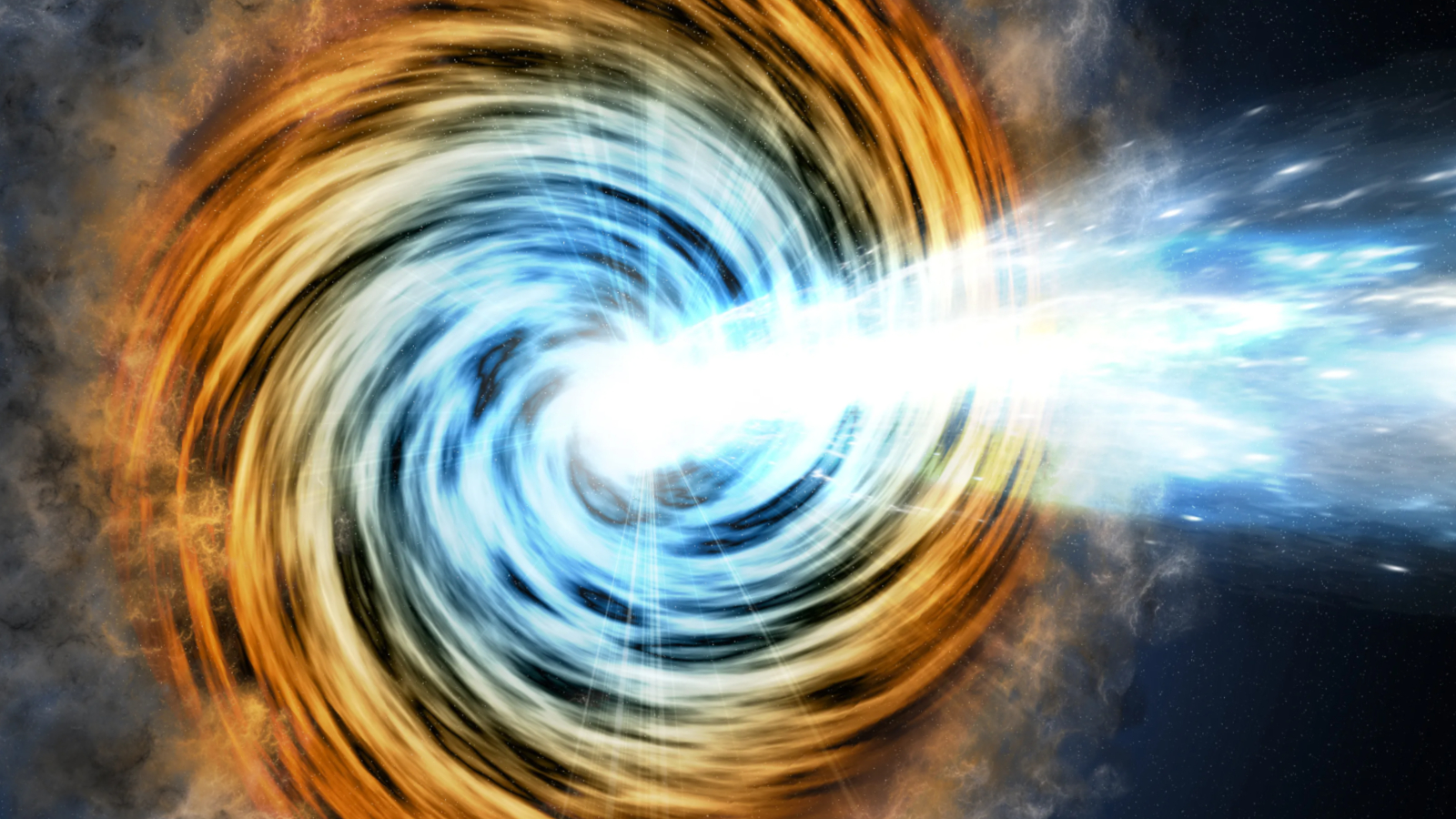

Some supermassive black holes, known as quasars, are so massive they can superheat the material doom-spiraling within their accretion disk to hundreds of thousands of degrees, at which point they emit huge amounts of electromagnetic radiation. The quasars' immense magnetic fields can sculpt this energy into twin jets that shoot out perpendicularly to accretion disks and extend well beyond their host galaxies.

By chance, some of these quasars point one of their twin jets directly at Earth, creating radio bright spots that pulse as these black holes consume matter. These black holes are known as blazars.

In the new study, published Dec. 18, 2024, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers discovered a new blazar, dubbed J0410−0139, using data from multiple telescopes, including the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, the Magellan telescopes and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope — all located in Chile — and NASA's Chandra observatory in Earth-orbit.

Radio waves from this blazar traveled more than 12.9 billion light-years to reach us, which is a new record for this type of cosmic object. The shining behemoth's remarkable age could enable researchers to learn more about how the first supermassive black holes took shape and how these galactic nuclei have evolved ever since.

Related: Object mistaken as a galaxy is actually a black hole pointed directly at Earth

"The alignment of J0410−0139's jet with our line of sight allows astronomers to peer directly into the heart of this cosmic powerhouse," study co-author Emmanuel Momjian, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Virginia, said in a statement. "This blazar offers a unique laboratory to study the interplay between jets, black holes, and their environments during one of the universe’s most transformative epochs."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Oldest blazar yet

Fewer than 3,000 blazars have been discovered to date, and most have been located much closer to Earth than J0410−0139. The previous record holder for the most distant blazar was PSO J0309+27, which was discovered in 2020 and is around 12.8 billion light-years from Earth, making it around 100 million years younger than J0410−0139.

Compared to the age of the universe, this age difference seems tiny. However, in those 100 million years, a supermassive black hole could grow by several orders of magnitude, making this a significant development.

Finding one blazar at this distance hints that many other supermassive black holes existed at this point in cosmic history that either had no jets or beamed their radiation away from Earth, study lead author Eduardo Bañados, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, said in another statement.

"Imagine that you read about someone who has won $100 million in a lottery," Bañados said. "Given how rare such a win is, you can immediately deduce that there must have been many more people who participated in that lottery but have not won such an exorbitant amount. Similarly, finding one [quasar] with a jet pointing directly toward us implies that at that time, there must have been many [quasars] in that period of cosmic history with jets that do not point at us."

The researchers will now hunt for more blazars from this time and are confident they will find some. "Where there is one, there's one hundred more [waiting to be found]," study co-author Silvia Belladitta, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, said in the statement.

Black hole quiz

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.