'Dark comets' may be a much bigger threat to Earth than we thought, new study warns

A strange class of space rock known as a "dark comet" has qualities of both asteroids and comets — and the hard-to-spot objects may pose a larger threat to Earth than we thought, according to new research.

Mysterious, nearly invisible objects known as "dark comets" may pose a bigger threat to Earth than scientists thought, new research suggests.

These small, rapidly spinning objects wander near Earth, likely after migrating from more distant reaches of the solar system. They might be a source of water and other volatile elements — and also a potent source of danger.

Usually, comets are very distinct from asteroids. Comets come from the outermost region of the solar system, where temperatures are low enough to allow molecules like water to freeze. While comets typically have stable orbits, occasionally they can be disturbed by gravitational interactions with the giant planets, sending some of the icy rocks spiraling toward the inner solar system. When they do, the heat from the sun causes them to disintegrate — a process that also gives comets their signature tails.

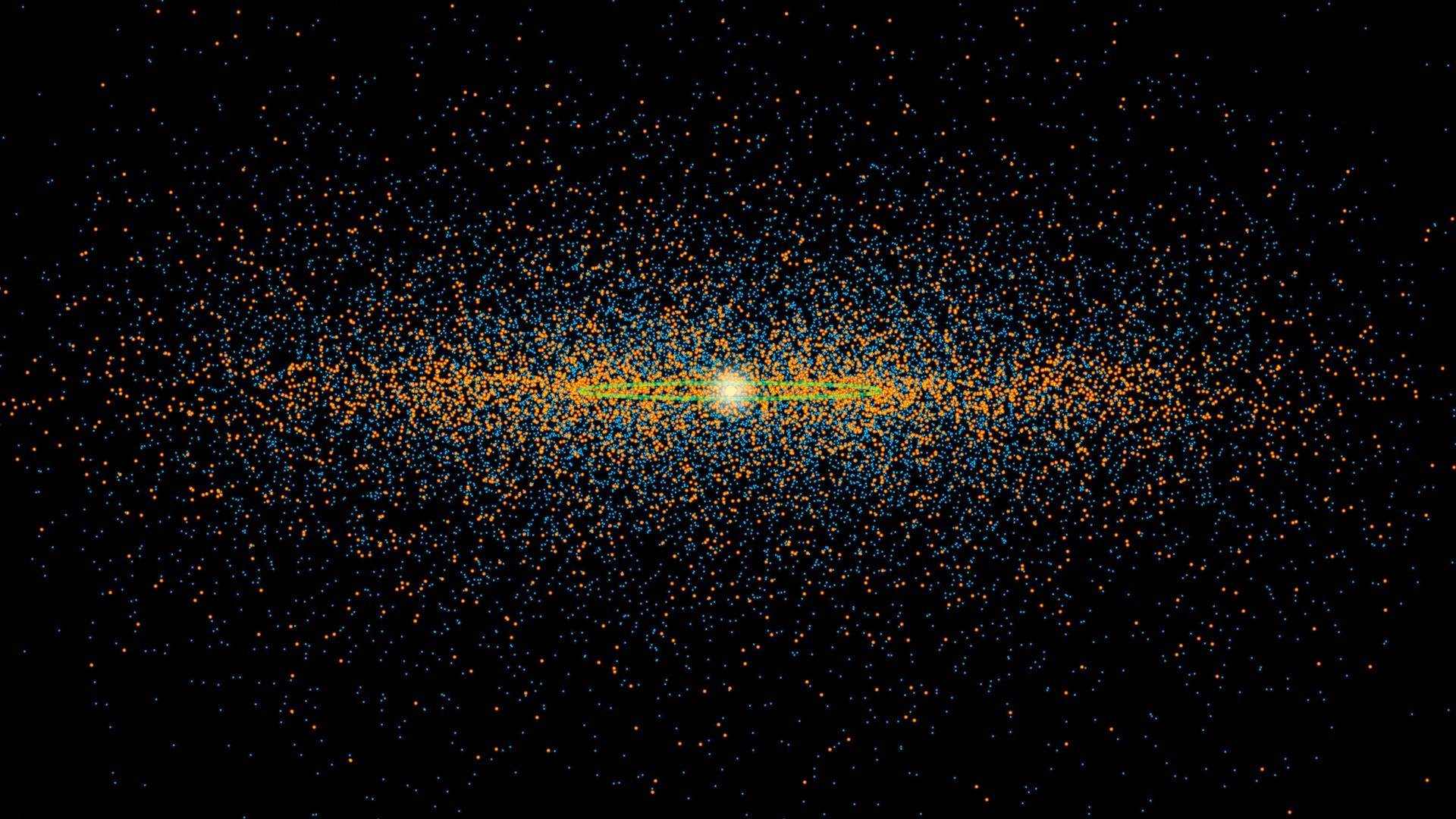

Asteroids, on the other hand, typically live in the inner solar system, usually between Mars and Jupiter. They are much rockier than their cometary cousins and, therefore, can survive much longer in the glare of the sun. But they, too, occasionally tumble into unstable orbits that bring them dangerously close to Earth.

But there's a strange, third type of space rock that astronomers have only recently begun to identify: dark comets, which behave like both asteroids and comets. Now, in a paper accepted for publication in the journal Icarus, a team of astronomers has tried to identify the mysterious origins of dark comets.

Dark comets are small — only tens of kilometers across. They show no visible outgassing or evaporation of volatile elements like water. But they don't move in perfect orbits, either. Instead, they show evidence for "nongravitational" acceleration, implying that there are some other forces capable of gently nudging their orbits.

All small objects in the solar system, including asteroids, have some amount of nongravitational acceleration, but astronomers can usually identify the cause. For example, asteroids are unevenly heated by the sun, which causes a tiny-but-measurable shift in their orbits.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: There may be a 'dark mirror' universe within ours where atoms failed to form, new study suggests

The researchers discovered that the nongravitational acceleration of dark comets is not compatible with uneven heating, so there must be another source of acceleration. The team thinks the dark comets are indeed outgassing, which can cause its own nongravitational acceleration, just at an undetectable level.

The dark comets also spin very rapidly, which means that they must have enough internal strength not to tear themselves apart. From that, the researchers concluded that dark comets have similar compositions as asteroids and are probably the result of a larger object fragmenting.

Based on these lines of evidence, the researchers suspect that dark comets likely originate in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and are disturbed from their orbits through gravitational interactions with Saturn. So dark comets are likely asteroids, but of a strange flavor — they are asteroids loaded with an unusually large amount of light molecules, like water, that can evaporate when the objects enter the inner solar system. Therefore, the researchers suggest that dark comets may be a possible candidate for how early Earth got its water.

Meanwhile, the unstable orbits of dark comets and their unlikely combination of properties make them especially dangerous near-Earth objects. They are small, fast and hard to detect. Most importantly, they don't behave how their more familiar asteroid and comet cousins do, making them unpredictable, the researchers found.

To help safeguard Earth from possible threats, we will need to study rogue populations like dark comets in much more detail to better detect them and predict their future movements.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.