Green comet Nishimura has passed its closest point to Earth, and it won't be back for another 430 years

The comet Nishimura, which was only discovered in August, will soon be slingshotted around the sun and back out toward the edge of the solar system where it will remain for centuries.

An extremely bright comet that was only discovered last month has made its closest approach to Earth as it falls rapidly toward the sun. The icy object, known as "Comet Nishimura," will soon be slingshotted around our star and back into the outer reaches of the solar system, where it will remain for the next four centuries.

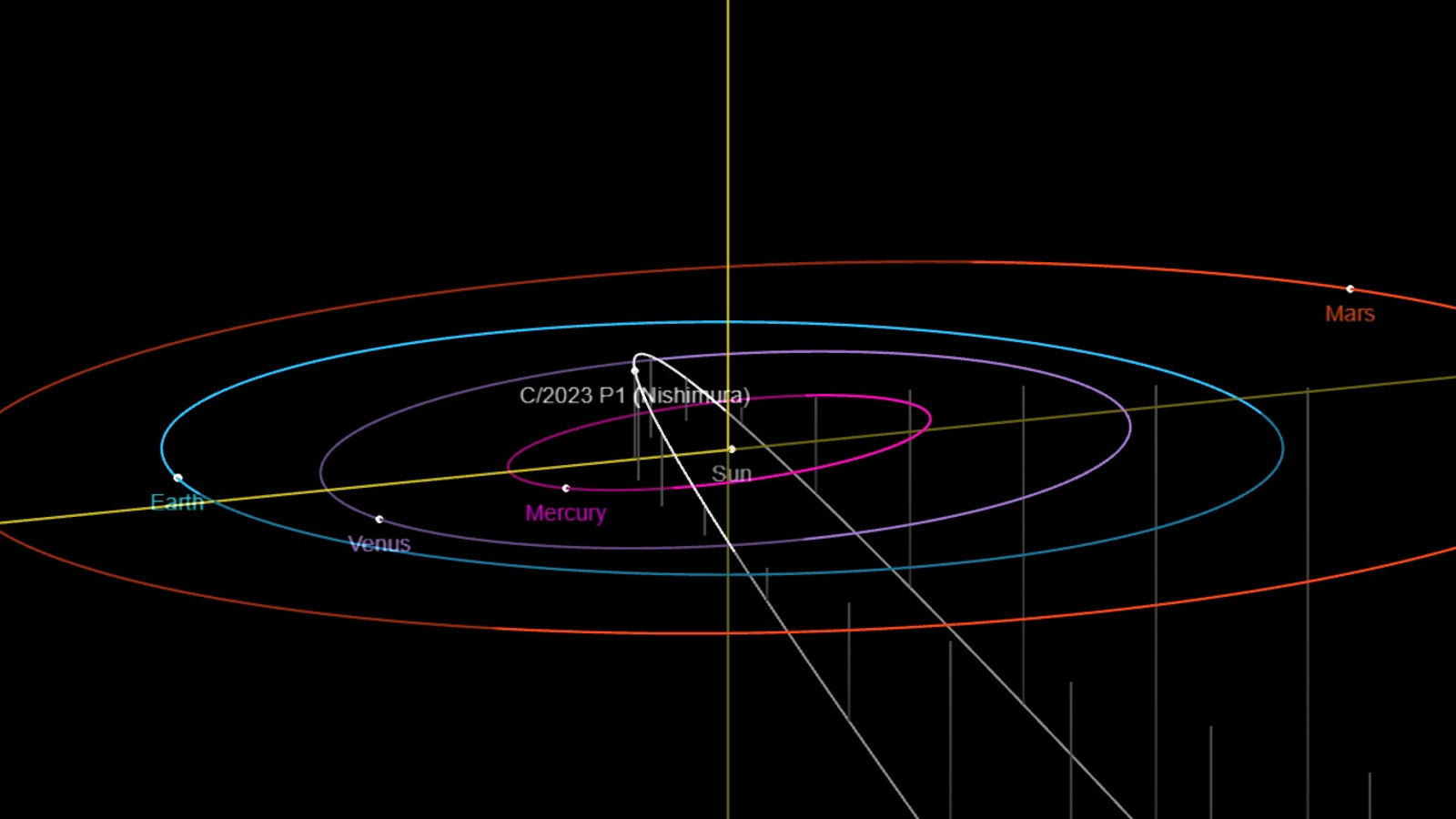

The comet, which gives off a green glow, was discovered Aug. 12 by amateur Japanese astronomer Hideo Nishimura. The object, also designated C/2023 P1, likely originates from the Oort Cloud — a reservoir of comets and other icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune — and has a steep elliptical orbit, which means it spends most of its orbit in the outer solar system before rapidly falling toward the sun and slingshotting around it.

Comet Nishimura's unusual orbit initially hinted it might be an interstellar comet that originated from outside the solar system, such as 'Oumuamua and Comet 2I/Borisov. If this was the case, this appearance would have likely been its first and only journey into the inner solar system. However, further observations have shown its orbit around the sun likely lasts around 430 years, according to NASA via AP News.

Comet Nishimura reached its closest distance to Earth on Sept. 12, when it passed within 78 million miles (125 million kilometers) of our planet. The comet's perihelion, or closest point to the sun, will occur on Sept. 17 when the icy object passes within 20.5 million miles (33 million km) of our home star. It will then be slingshotted back into the outer solar system — if it isn't burned up by its solar encounter.

Related: City-size comet headed toward Earth 'grows horns' after massive volcanic eruption

Comet Nishimura has become increasingly bright on its journey into the solar system, reaching an equivalent magnitude of a small star. This brightening is caused by an outpouring of gas from the comet's interior, which is released as its surface is battered with solar wind and radiation, and will continue until it reaches perihelion with the sun.

The comet's coma — the cloud of gas and dust that surrounds its solid core — gives off a green light because it contains molecules of dicarbon, which emit green light when they are broken down by sunlight, according to Science magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the past week, stunning shots of the shining comet have been captured. On Sept. 9, astrophotographer Jeremy Perez snapped a stunning shot of the comet in the sky above Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument in Arizona (see above). And on the same day, astrophotographer Petr Horalek, also captured the comet above the town of Zahradne in Slovakia (see below).

The comet has been most clearly visible from the Northern Hemisphere just before sunset due to its position relative to Earth. However, further high-quality sightings of the comet from Earth are unlikely. Despite becoming even brighter over the next few days, Comet Nishimura will become harder to spot in the night sky. As the comet gets closer to the sun, the star's own light will outshine the comet making it almost impossible to pick out and completely obscuring its tail, according to Spaceweather.com.

The comet has also caused a stir among astronomers after being bashed by two coronal mass ejections (CMEs) — fast-moving clouds of magnetized plasma and radiation that erupt from the sun alongside solar flares. The solar storms have not altered the comet's trajectory but they did briefly disrupt the comet's long tail, which is made up of a stream of dust and gas that is blown off the comet, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com.

Astronomers are still unsure exactly where Comet Nishimura came from, but some experts believe it could be partially tied to the Sigma-Hydrids meteor shower, a minor shower that peaks in early December every year, according to the astronomy news site EarthSky. If this is the case, then this year's shower could be much more active and visually stunning than normal.

Editor's note: This article has been corrected to say the comet's orbit is elliptical, not hyperbolic

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.