Mysterious, city-size 'centaur' comet gets 300 times brighter after quadruple cold-volcanic eruption

The cryovolcanic "centaur" comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann has erupted four times in less than 48 hours, becoming unusually bright in the process. It is the most powerful outburst from the city-size oddball in more than three years.

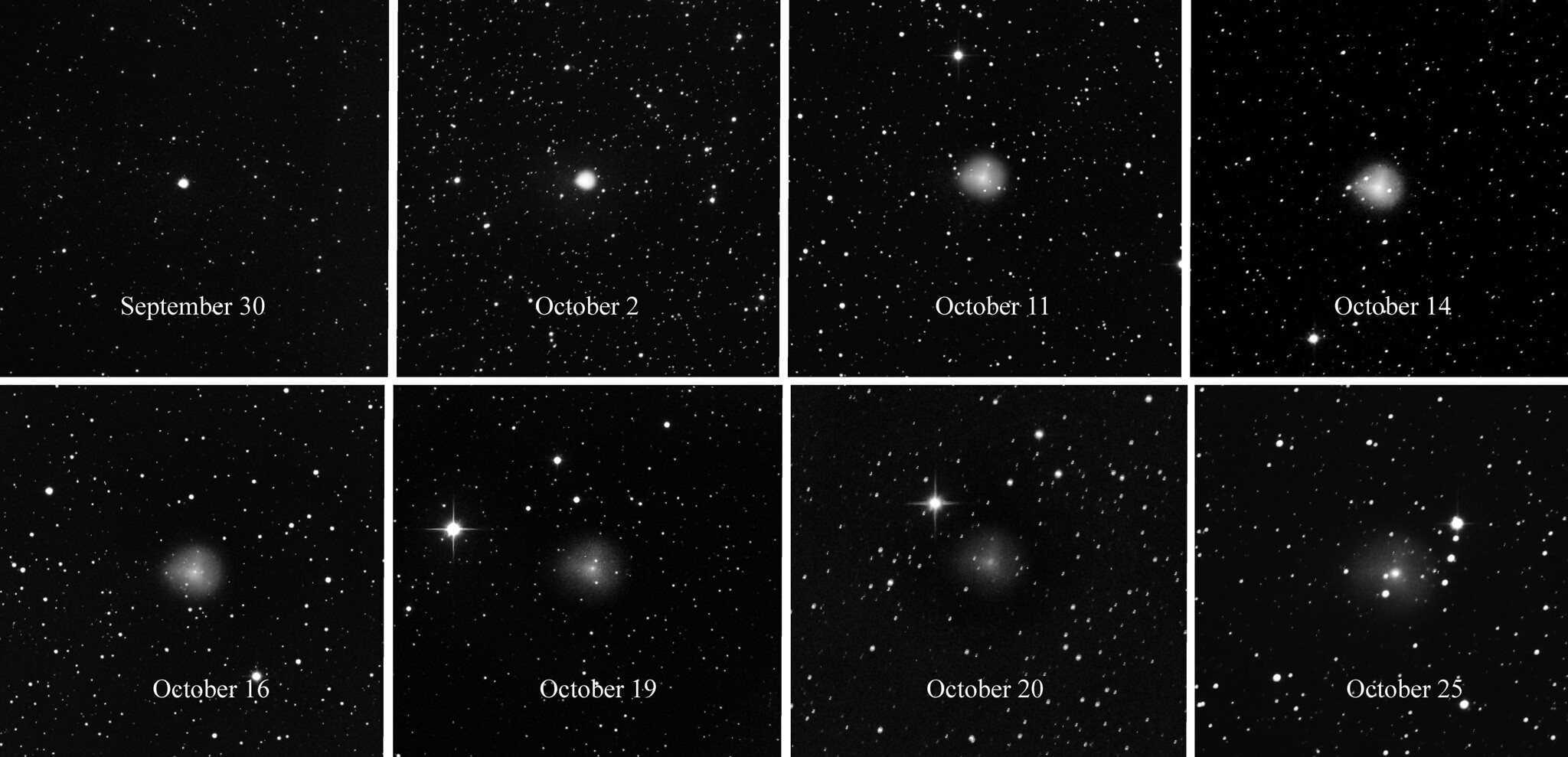

A mysterious volcanic comet has just reawoken, unleashing four major eruptions in less than 48 hours and spraying out enough of its icy guts to make the city-size object appear almost 300 times brighter than normal, researchers say. The latest outbursts, which are the largest in more than three years, add to the growing confusion about when and why this explosive oddball blows its top.

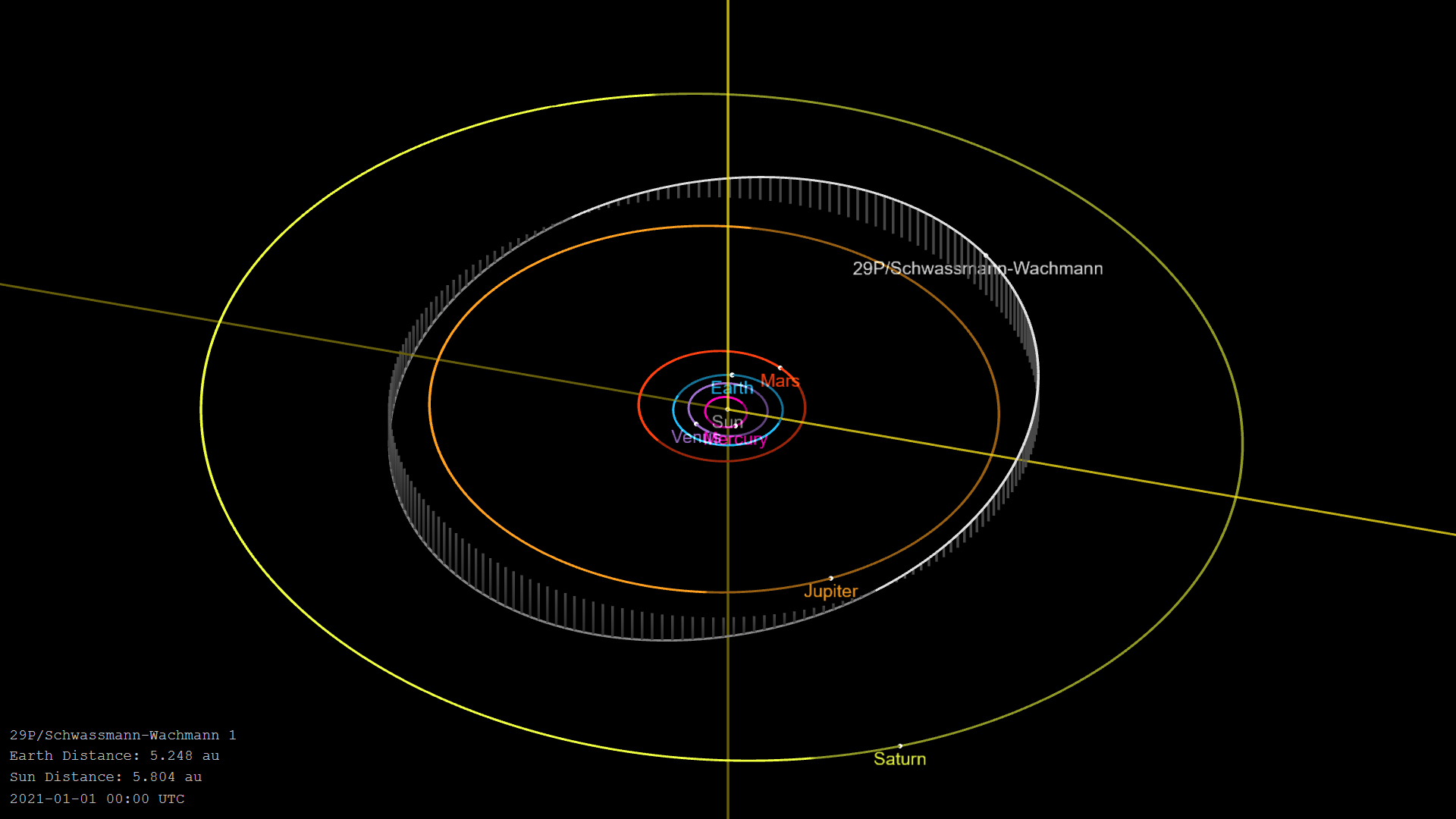

The comet, known as 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann (29P), is a large icy object spanning around 37 miles (60 kilometers) across — around three times the length of Manhattan. It is one of around 500 comets known as "centaurs" that spend their entire lives confined to the inner solar system. However, 29P is also part of an even rarer group, known as cryovolcanic, or cold volcano, comets.

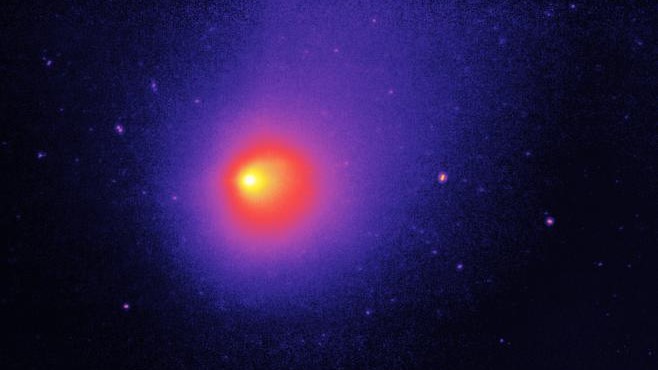

Cryovolcanic comets consist of an icy shell, or nucleus, filled with ice, dust and gas. When the comet soaks up enough of the sun's radiation, its frosty innards get superheated. Pressure builds within the nucleus until the shell cracks and the comet's icy guts, or cryomagma, spray into space. After an eruption, or outburst, the comet's coma — a fuzzy, reflective cloud of cryomagma — expands, making the comet appear much brighter as it reflects more of the sun's rays. A previous example of this was comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, or "the devil comet," which grabbed headlines during its close approach to Earth over the last 18 months.

On Nov. 2, 29P experienced its first major eruption for almost two years, which was quickly followed by three more large outbursts in less than 48 hours, according to observations listed by the British Astronomical Association (BAA), which has been closely tracking 29P. The four eruptions expelled a cloud of debris that reflected 289 times more light than the comet's nucleus, BAA astronomers wrote.

Experts predict that as the coma expands it could take on an unusual shape, similar to the initial eruptions of the devil comet, due to the multiple outbursts. "I expect to see the development of a complex expanding debris cloud over the next few days," Richard Miles, an astronomer at BAA, told Spaceweather.com.

Related: Watch the biggest-ever comet outburst spray dust across the cosmos

This was 29P's first major eruption since November 2022, when it spewed more than 1 million tons of debris into space. It is also the largest outburst since September 2021, when the comet blew its top five times in quick succession.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In April 2023, scientists successfully predicted an eruption from 29P for the first time, when the comet popped its top "like a champagne bottle." However, predicting eruptions is extremely difficult because most of the comet's outbursts happen very sporadically and at random — a behavior that researchers have been unable to explain.

Most cryovolcanic comets orbit the sun on highly elliptical orbits that take them to the outer reaches of the solar system for decades, centuries or even thousands of years at a time. It is only when they race into the inner solar system that they start to regularly explode before being slingshotted back to the outer solar system.

However, 29P orbits the sun once every 15 years and has a circular orbit around the sun at a similar distance from our homestar as Jupiter, meaning the amount of solar radiation it absorbs remains mostly constant. As a result, it should erupt fairly regularly and evenly. But detailed observations of the comet over the last few decades show that this is not the case, hinting that something unknown influences when it erupts, according to BAA.

Because 29P never gets close to the sun, it also never grows a tail, like the one that trailed behind the "once-in-a-century" comet, Tshuminchan-ATLAS, which lit up Earth's skies as it made its closest approach to Earth for 80,000 years last month.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.