1st supernovas may have flooded the early universe with water — making life possible just 100 million years after the Big Bang

A new study suggests that the explosive deaths of the universe's earliest stars created surprising quantities of water that may have sparked extraterrestrial life in the very first galaxies.

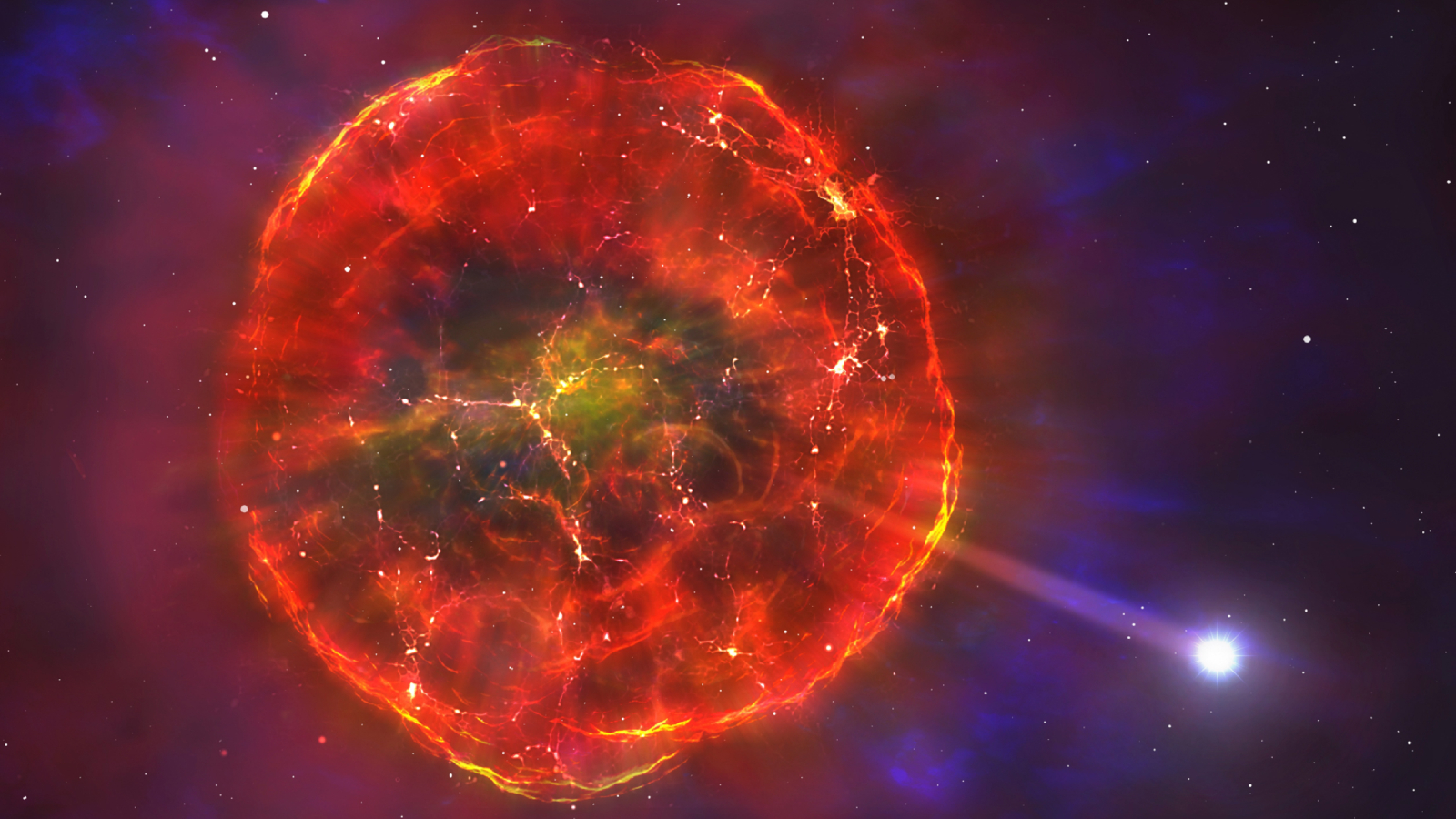

When the cosmos' first stars exploded in spectacular supernovas, they may have unleashed enormous amounts of water that flooded the early universe — and potentially made life possible just millions of years after the Big Bang, new simulations suggest.

However, this theory clashes with our current understanding of cosmic evolution and will be extremely difficult to prove.

Water is one of the most abundant compounds in the universe, according to NASA. Aside from Earth, astronomers have found water in several places throughout the solar system, including scattered above and below the surface of Mars, inside the ice caps of Mercury, surrounding the shells of comets and buried in underground oceans on several major moons. Outside our cosmic neighborhood, researchers have also detected water on distant exoplanets and within massive clouds of interstellar gas that permeate the Milky Way.

Until now, scientists assumed that all this water gradually built up over billions of years as hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, combined with oxygen that has been forged in the hearts of stars and expelled via supernovas. But in the new study, uploaded Jan. 9 to the preprint server arXiv, researchers simulated the explosive deaths of giant, short-lived early stars — which each had a mass equivalent to around 200 suns — and found that they could create the conditions needed for water to take shape.

The water from these stellar explosions would likely have formed at the hearts of dense clouds of hydrogen, oxygen and other elements left behind by stars. It may have had concentrations up to 30 times higher than the water seen floating in interstellar space within the Milky Way, the researchers wrote in the study, which has not been peer-reviewed yet.

Related: Could a supernova ever destroy Earth?

If correct, the new findings would have big implications for scientists' understanding of galaxy evolution and extraterrestrial life.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Besides revealing that a primary ingredient for life was already in place in the universe between 100 million and 200 million years after the Big Bang, our simulations show that water was likely a key constituent of the first galaxies," the researchers wrote.

Early cosmic uncertainty

One of the biggest issues with the new study is that scientists have never directly observed one of the early stars that the researchers are modeling, known as population III stars. Instead, researchers have only indirectly observed a few of these stellar trailblazers by analyzing the stars that were birthed from their remains, so it's still not certain what they were really like.

If there was abundant water in the early universe, it would also suggest that the cosmos should have accumulated much more water than we currently see in our surroundings.

One explanation for this that has been posited by other scientists is that the universe underwent a drying-out period during which large quantities of water were lost, according to Universe Today. However, it is unclear what the cause of this event could have been.

"There is also the fact that while water formed early, ionization and other astrophysical processes may have broken up many of these molecules," Universe Today reported, meaning that the water from the first supernovas may have been short-lived.

Although water is a key ingredient for life on Earth, there is also no guarantee that its presence in the early universe would have made extraterrestrial life more likely.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.