Could the universe ever stop expanding? New theory proposes a cosmic 'off switch'

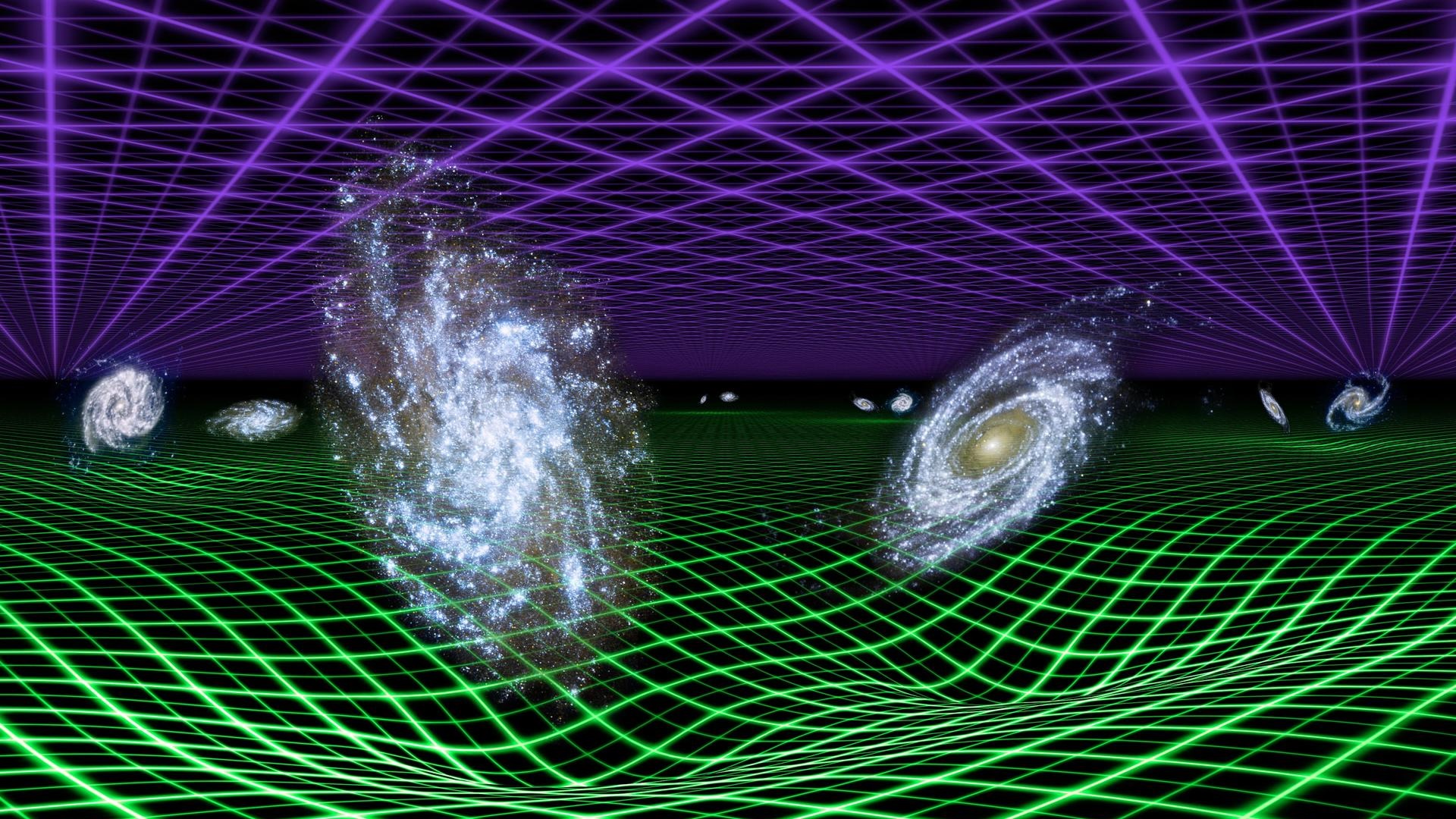

Dark energy, the mysterious phenomenon that powers the expansion of the universe, may undergo periodic 'violent transitions' that reverse the growth of the cosmos, a new pre-print study hints.

Dark energy may have switched directions sometime in the distant past — and this violent transition may explain why cosmological observations aren't adding up, researchers propose in a new paper.

The modern picture of the evolution of the universe is known as ΛCDM (or lambda-CDM), for dark energy (represented by the Greek letter Λ) and cold dark matter. Dark energy is the mysterious force driving the accelerating expansion of the universe, and cold dark matter refers to the mysterious, invisible substance that provides most of the mass of almost every single galaxy.

This model has explained a wide variety of observations, such as the behavior of galaxies and clusters, the growth of large-scale structures, and the appearance of the cosmic microwave background. But in recent years, two troubling tensions have popped up.

One such problem, known as the Hubble tension, is a difference in measuring the present-day expansion rate of the universe, a number known as the Hubble constant. Probes of the distant, early universe seem to be giving estimates significantly lower than probes of the nearby, late universe do.

Related: After 2 years in space, the James Webb telescope has broken cosmology. Can it be fixed?

Related to this issue is the second problem, known as the sigma-8 tension. This is a measure of how clumpy matter is in the universe, and once again, different probes are yielding different results.

A cosmic slowdown

Something in the ΛCDM model has to be wrong, but we're not sure what. One hypothesis is that dark energy might be more dynamic than we originally thought. In the usual ΛCDM picture, dark energy is a cosmological constant. It stays the same through cosmic history.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But in a recent model that's been gaining interest, dark energy changes. And not by a little; it undergoes a complete phase transition, from decelerating the universe to accelerating the universe.

Now, adding a twist to that theory, a research team has explored the possibility that the phase change is even more dramatic. In a paper posted to the preprint server arXiv in February but not yet peer-reviewed, dark energy doesn't just switch signs; it also changes strength, so that it powers an acceleration differently than it powers a deceleration.

Then, the researchers tested their model against a wide variety of observations and datasets. These included the Planck space observatory's measurements of the cosmic microwave background, the oldest light we can see in the universe; a measurement of a phenomenon called the baryon acoustic oscillation, a pattern in the arrangement of galaxies at very large scales; the Pantheon dataset of supernova distance measures; and a weak lensing map that provides details accounting for the effects of dark matter.

They found that the new model alleviated some of the Hubble and sigma-8 tensions, and thus they contend that this approach might be a promising way forward.

That said, the researchers noted that this model isn't exactly grounded in known physics. It's just a toy, a way to explore the physical consequences of a model without knowing the underlying physics. But because it seems like a promising direction, this approach could motivate theorists to come up with mechanisms to explain how dark energy might switch like this.

No matter what, it appears that the universe — especially dark energy — is more complicated than we assumed.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.