Group of 60 ultra-faint stars orbiting the Milky Way could be new type of galaxy never seen before

A new satellite galaxy discovered orbiting the Milky Way is either an incredibly ancient, soon-to-fragment clump of stars or the most dark-matter-dominated dwarf galaxy ever found.

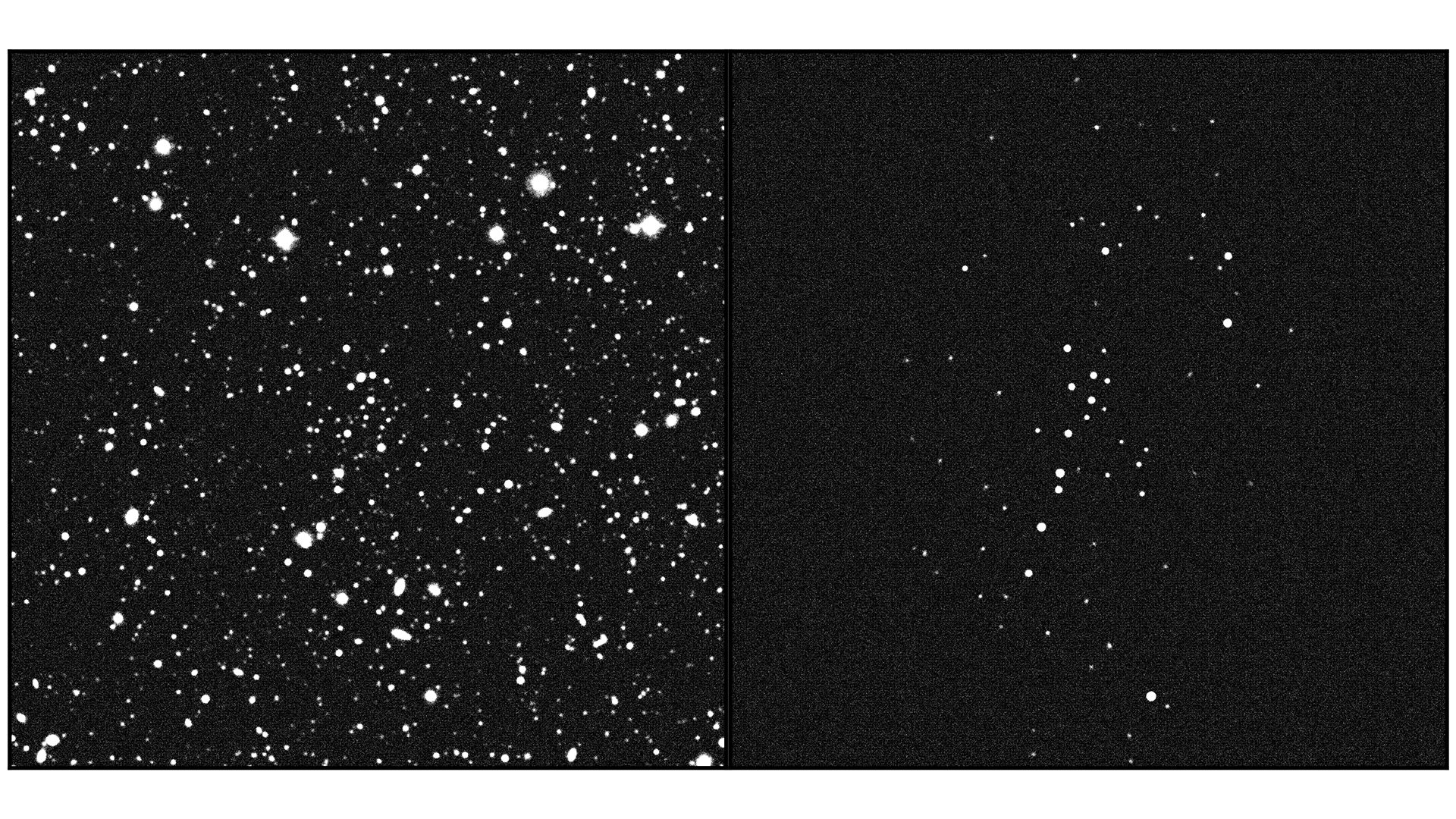

Astronomers have spotted the faintest and lightest satellite galaxy ever found: a minuscule, tight-knit group of stars trailing the Milky Way. The peculiar discovery could represent a new class of impossibly faint, dark-matter-dominated star systems that had eluded detection until now.

Tentatively named Ursa Major III/Unions 1 (UMa3/U1), the newfound star system resides in the constellation Ursa Major, about 30,000 light-years from the sun. It is the newest addition to our galaxy's assortment of at least 50 satellite galaxies. Even the smallest of these galaxies host thousands to billions of stars.

The newfound system, by contrast, has just a sprinkling of 60 stars. As such, its mass is just 16 times the mass of the sun, scientists reported in a new study. For comparison, the Milky Way's mass is about 1.5 trillion times that of our star, according to NASA.

UMa3/U1 also defies the conventional image of a distinctively shaped galaxy.

"This discovery may challenge our understanding of galaxy formation and perhaps even the definition of a 'galaxy,'" Simon Smith, a graduate student at the University of Victoria in Canada and the lead author of the study, said in a statement. "UMa3/U1 had escaped detection until now due to its extremely low luminosity."

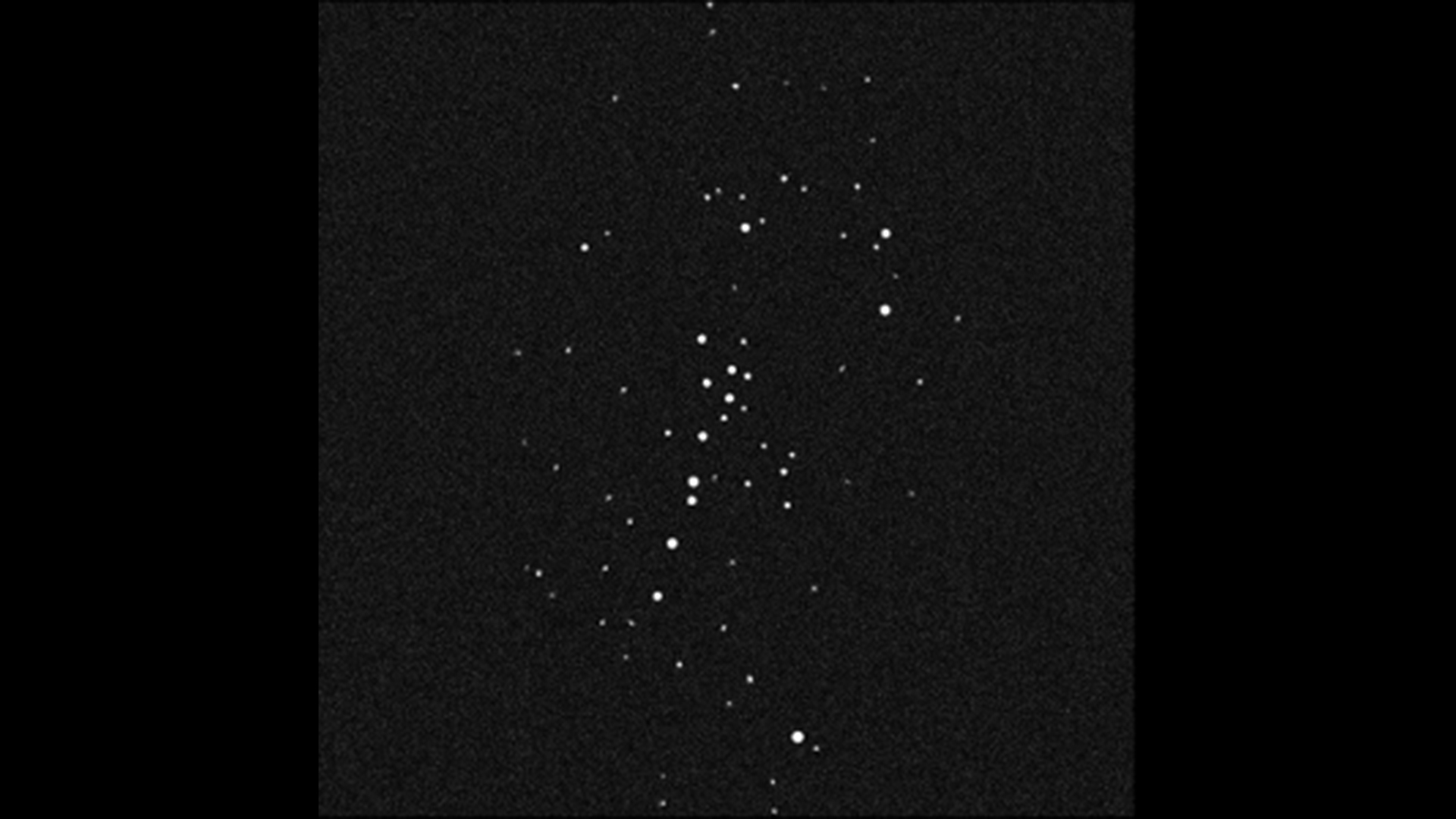

Scientists first spotted UMa3/U1 as a collection of bright stars spanning 10 light-years in data collected by the Ultraviolet Near Infrared Optical Northern Survey, a project by the Canada France Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) that surveys the northern sky using three Hawaii-based telescopes. Follow-up observations using the W. M. Keck Observatory confirmed that the stars are gravitationally bound and have similar chemistries, according to the study, which was published in January in The Astrophysical Journal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers are baffled by how the diminutive UMa3/U1 has remained intact for at least 10 billion years, which is the estimated age of its stellar residents and more than twice the age of our own 4.6 billion-year-old sun. From observations of other eccentric stars in the Milky Way, astronomers know that our galaxy's gravitational pull, also called the tidal force, has previously wrenched apart dwarf galaxies that ventured too close. For instance, a well-known cannibalized galaxy is Gaia-Enceladus, which our home galaxy ripped apart about 8 billion to 10 billion years ago.

Yet, although UMa3/U1's orbit takes it through inner regions of the Milky Way, where our galaxy's tidal forces are the strongest, the dwarf galaxy appears to have escaped destruction for eons.

"The object is so puny that its long-term survival is very surprising," Will Cerny, a graduate student in the Yale University Department of Astronomy and a co-author of the study, said in the statement. "Either UMa3/U1 is a tiny galaxy stabilized by large amounts of dark matter, or it's a star cluster we've observed at a very special time before its imminent demise."

The former possibility is particularly exciting because in galaxies elsewhere in the universe, astronomers have so far been unsuccessful in detecting dark matter, the invisible substance thought to make up the majority of the matter in our cosmos. If dark matter is indeed responsible for holding the newfound star system together, future observations could offer valuable clues about dark matter's composition and behavior, the study authors said.

"Whether future observations confirm or reject that this system contains a large amount of dark matter, we're very excited by the possibility that this object could be the tip of the iceberg — that it could be the first example of a new class of extremely faint stellar systems that have eluded detection until now," Cerny concluded.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social