'I was astonished': Ancient galaxy discovered by James Webb telescope contains the oldest oxygen scientists have ever seen

Scientists have made the record-breaking detection of oxygen in an ancient galaxy that existed just 300 million years after the Big Bang. The detection is prompting astronomers to rethink how quickly stars and galaxies formed in the young universe.

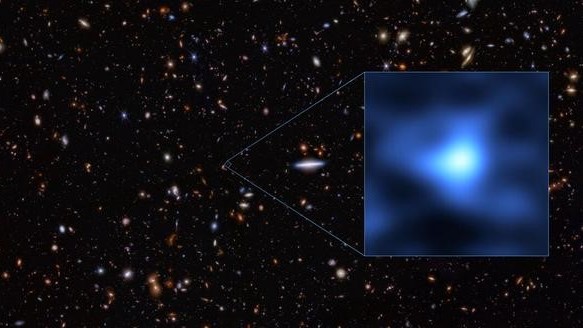

Astronomers have found oxygen in the most distant known galaxy, upending assumptions about how quickly galaxies matured.

Named JADES-GS-z14-0, the galaxy where the record-breaking detection was made formed at least 290 million years after the Big Bang and was first spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2024.

Heavy elements like oxygen are forged in the nuclear fires of stars. As the newfound oxygen existed when the universe was just 2% of its present age, this primordial element is a major head-scratcher for astronomers because it suggests that stars in the early universe were born and died to seed their surroundings with heavy elements much faster than previously expected. The findings, made by two different research teams, were published March 20 in two papers in the journals Astronomy & Astrophysics and The Astrophysical Journal.

"It is like finding an adolescent where you would only expect babies," Sander Schouws, a researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands and lead author of the second study, said in a statement. "The results show the galaxy has formed very rapidly and is also maturing rapidly, adding to a growing body of evidence that the formation of galaxies happens much faster than was expected."

The earliest oxygen

Astronomers aren't certain when the first globules of stars began to clump into the galaxies we see today, but cosmologists previously estimated that the process began slowly within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

The detection of JADES-GS-z14-0 and other galaxies like it, however, turned this assumption on its head. The light detected by JWST's Near Infrared Spectrograph originated in an enormous halo of young stars surrounding the galaxy's core that were burning for at least 90 million years before its observation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Young stars are typically composed of hydrogen and helium, and they fuse them into heavier elements, like oxygen, as they grow old and scatter them throughout their host galaxies upon the stars' violent deaths. At the roughly 300 million-year mark where we can see JADES-GS-z14-0, astronomers expected the universe to still be too young to be rife with heavy elements.

But after pointing the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile's Atacama Desert at the distant galaxy, the researchers were stunned by what they found: JADES-GS-z14-0 had roughly 10 times more oxygen than they expected.

"I was astonished by the unexpected results because they opened a new view on the first phases of galaxy evolution," Stefano Carniani, an astronomer at the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa in Italy and lead author of the first paper, said in the statement. "The evidence that a galaxy is already mature in the infant universe raises questions about when and how galaxies formed."

How galaxies like JADES-GS-z14-0 birthed so many heavy-element-producing stars so quickly remains a mystery for further research. Currently, astronomers speculate that this surprisingly rapid element seeding could be due to the early appearance of gigantic black holes; feedback from other star deaths; or dark energy, the mysterious force that's driving the accelerated expansion of the universe.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.