James Webb telescope spots organic molecules swirling around unborn stars, hinting at origins of Earth-like worlds

Complex organic molecules spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope may hint at how habitable planets form.

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have spotted complex organic molecules swirling around two forming stars, hinting at where the building blocks of habitable planets originate.

Complex organic molecules are crucial for life, but their origin in space has been a mystery, according to Will Rocha, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands who led the team that made the observations. The new research suggests that these complex molecules arise during the sublimation of ice from solids into gas.

"This finding contributes to one of the long-standing questions in astrochemistry," Rocha said in a statement. "What is the origin of complex organic molecules, or COMs, in space? Are they made in the gas phase or in ices? The detection of COMs in ices suggests that solid-phase chemical reactions on the surfaces of cold dust grains can build complex kinds of molecules."

Related: Building blocks of life may have formed on dust in the cold vacuum of space

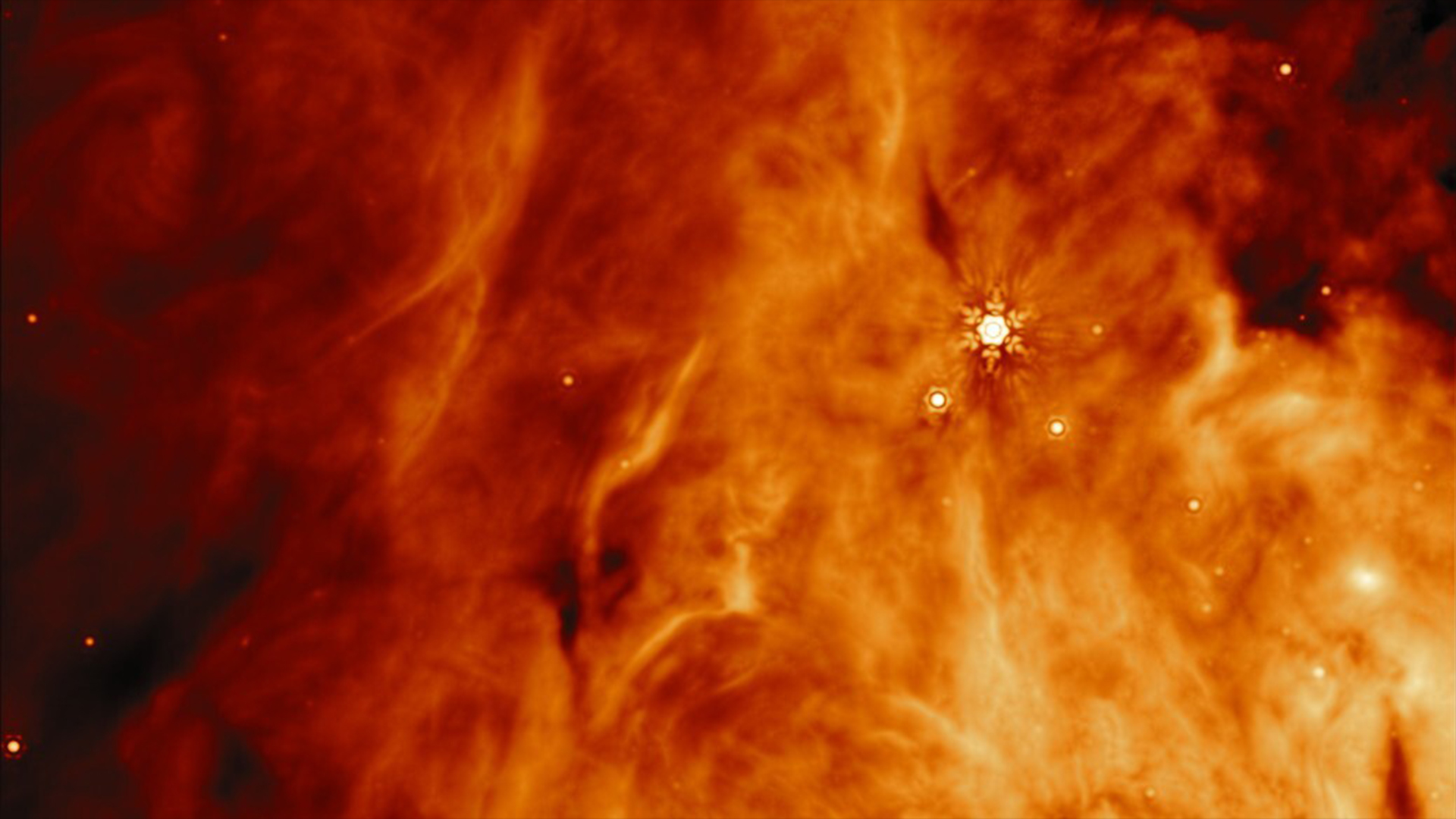

Rocha and his team used the JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument to peer into the materials surrounding two protostars: IRAS 2A and IRAS 23385. IRAS 2A was particularly interesting to the team, because it may be very similar to the first stars in the early stages of our own solar system, the researchers said.

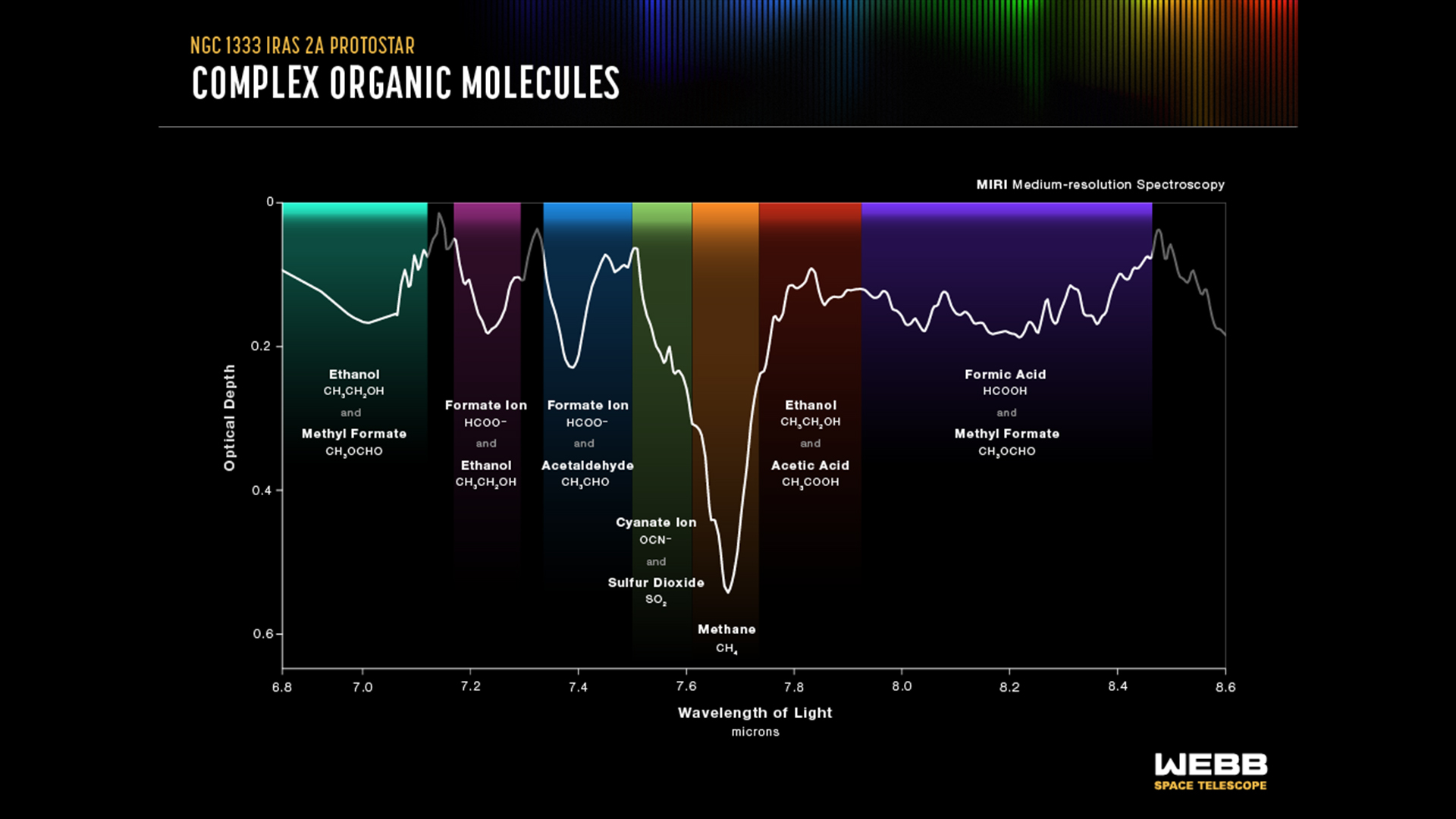

In the cold dust around these early-stage stars, they found icy compounds containing ethanol, acetic acid, formic acid, methane, formaldehyde and sulfur dioxide.

Some of the complex organics found in the ice have previously been found in warm gases around forming stars. According to the researchers, whose results will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, this finding suggests that the compounds are the result of a solid transitioning directly into a gas without passing through a liquid phase — a process called sublimation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Finding the complex organic molecules in ices also hints that these molecules may travel around galaxies easier than previously believed. An icy molecule can easily get swept up into a forming comet or asteroid, travel long distances, and then collide with forming planets, possibly delivering the building blocks for life to a place they can take root.

"All of these molecules can become part of comets and asteroids and eventually new planetary systems when the icy material is transported inward to the planet-forming disk as the protostellar system evolves," study co-author Ewine van Dishoeck, also of Leiden University, said in the statement. "We look forward to following this astrochemical trail step-by-step with more Webb data in the coming years."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.