Study of 'twin' stars finds 1 in 12 have killed and eaten a planet

A study of 91 pairs of stars finds that about 8%, or one in 12, swallowed up a planet at some point in their lives.

About one in every 12 stars may have swallowed a planet, a new study finds.

Previous research had discovered that some distant stars possess unusual levels of elements, such as iron, which one would expect to make up rocky worlds such as Earth. This and other evidence suggested that stars may sometimes ingest planets, but much remained uncertain about how often that might happen.

One way to uncover more about planetary ingestion is to look at two stars born at the same time. Such twins should have a virtually identical composition, as they are both born from the same parent cloud of gas and dust. Any major chemical differences between these so-called "co-natal" stars may thus be a sign that one devoured a world.

In the new study, the researchers used the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite to identify 91 pairs of stars. Within each traveling pair, the stars sit relatively close to one another — less than a million astronomical units apart — and are likely co-natal. An astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance between the sun and Earth, or about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Related: The James Webb telescope may have found some of the very 1st stars in the universe

When molecules are heated, they give off unique spectrums of light wavelengths corresponding to the elements they're made of. Scientists analyzing light coming from distant stars can therefore deduce the stars' elemental compositions as stellar molecules are exposed to very high temperatures.

The scientists used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile, the Magellan Telescope, also found in Chile, and the Keck Telescope in Hawaii to analyze the light from these co-natal stars. They found about 8 percent of these pairs — about one in 12 — had one star that displayed signs it had engulfed a planet. In other words, its chemical makeup differed when compared with its twin.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What's truly surprising is the frequency at which it seems to happen," study co-author Yuan-Sen Ting, an astronomer at the Australian National University in Canberra, told Space.com. "It implies that stable planetary systems like our own solar system might not be the norm. This gives us a deeper perspective on our place in the universe."

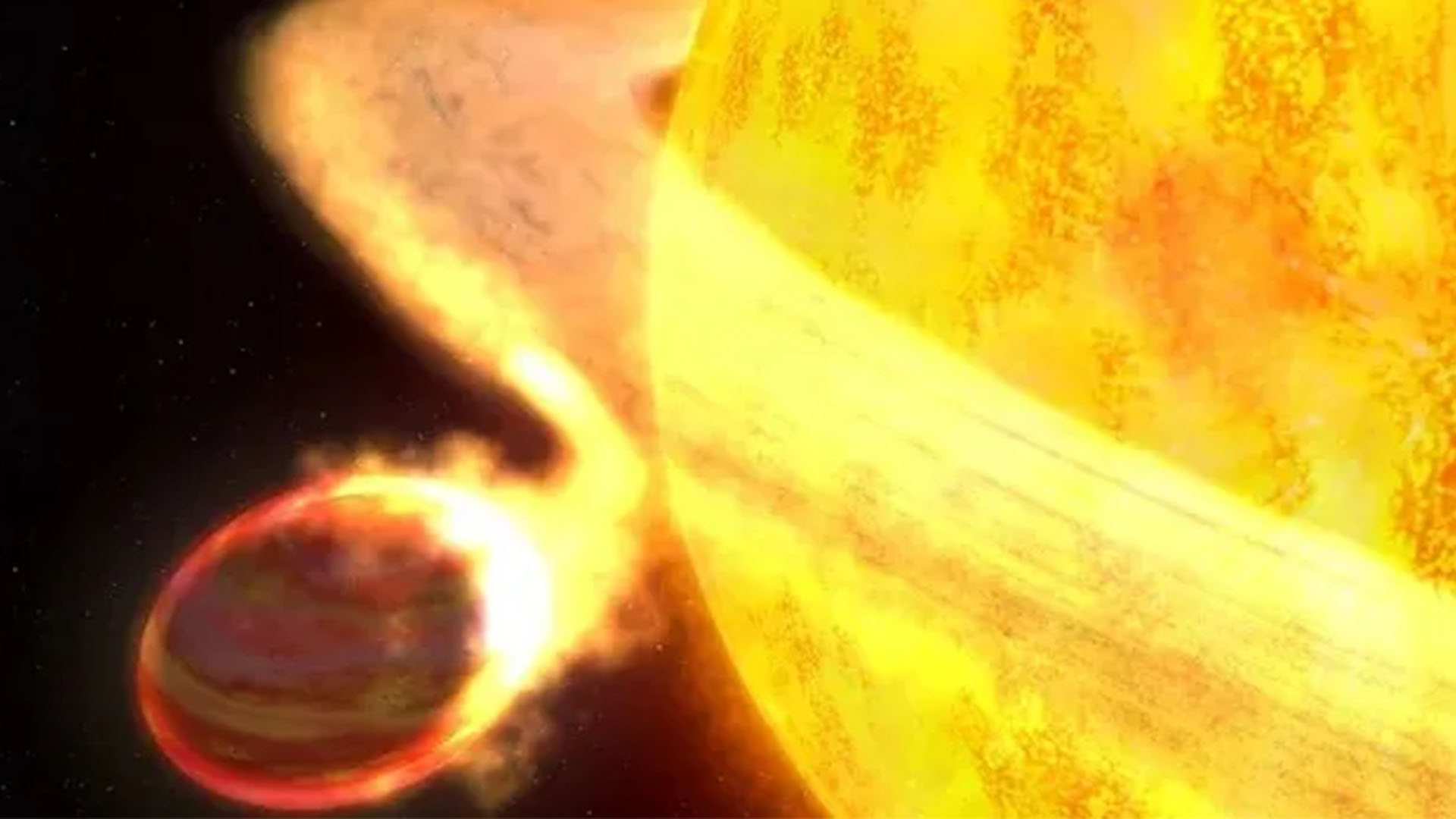

About 6 billion years from now, when our sun begins exhausting its primary source of fuel, it will swell to become a red giant star, likely swallowing closely orbiting planets. However, this new study examined stars that were in the prime of their lives. This suggests that planetary ingestion apparently happens during the normal lifetime of a star system, too — perhaps when a rogue planet gets hurled away from its parent star to collide with another star?

"The results suggest many planetary systems may be unstable, with some planets being ejected at random," Ting said. However, "while we found that many planetary systems might not be dynamically stable, our solar system, at least on a human timescale, is more than fine — don't worry!"

It remains uncertain whether the stars are swallowing planets, or engulfing the building blocks of planets left over from the births of star systems. Both may be possible, the researchers said.

The scientists detailed their findings online on March 20 in the journal Nature.

Originally posted on Space.com.