Supernova that lit up Earth's skies 843 years ago has a flowering 'zombie star' at its heart — and it's still exploding

A new animated map sheds light on the superhot "zombie star" at the heart of a nebula leftover from a distant supernova witnessed by astronomers in 1181. The remains of the stellar explosion are unusually wonky and are still exploding at a constant speed.

A first-of-its-kind, animated map has revealed fresh secrets about a mysterious, flowering "zombie star" lurking in the remnant of a supernova that lit up Earth's skies more than 800 years ago. The "3D movie" shows that the remains of the stellar explosion are unusually wonky and are still exploding at a constant speed.

In 1181, astronomers in China and Japan spotted a new star shining near the constellation Cassiopeia. Historical records of this "guest star" show that the bright spot persisted for around six months, from August of that year until February 1182.

Today, researchers know that the stellar imposter was actually a powerful supernova, or exploding star, known as SN 1181. However, its origin remained a mystery until 2021, when astronomers finally confirmed that the supernova came from the nebula Pa 30 — a giant cloud of gas wider than our entire solar system.

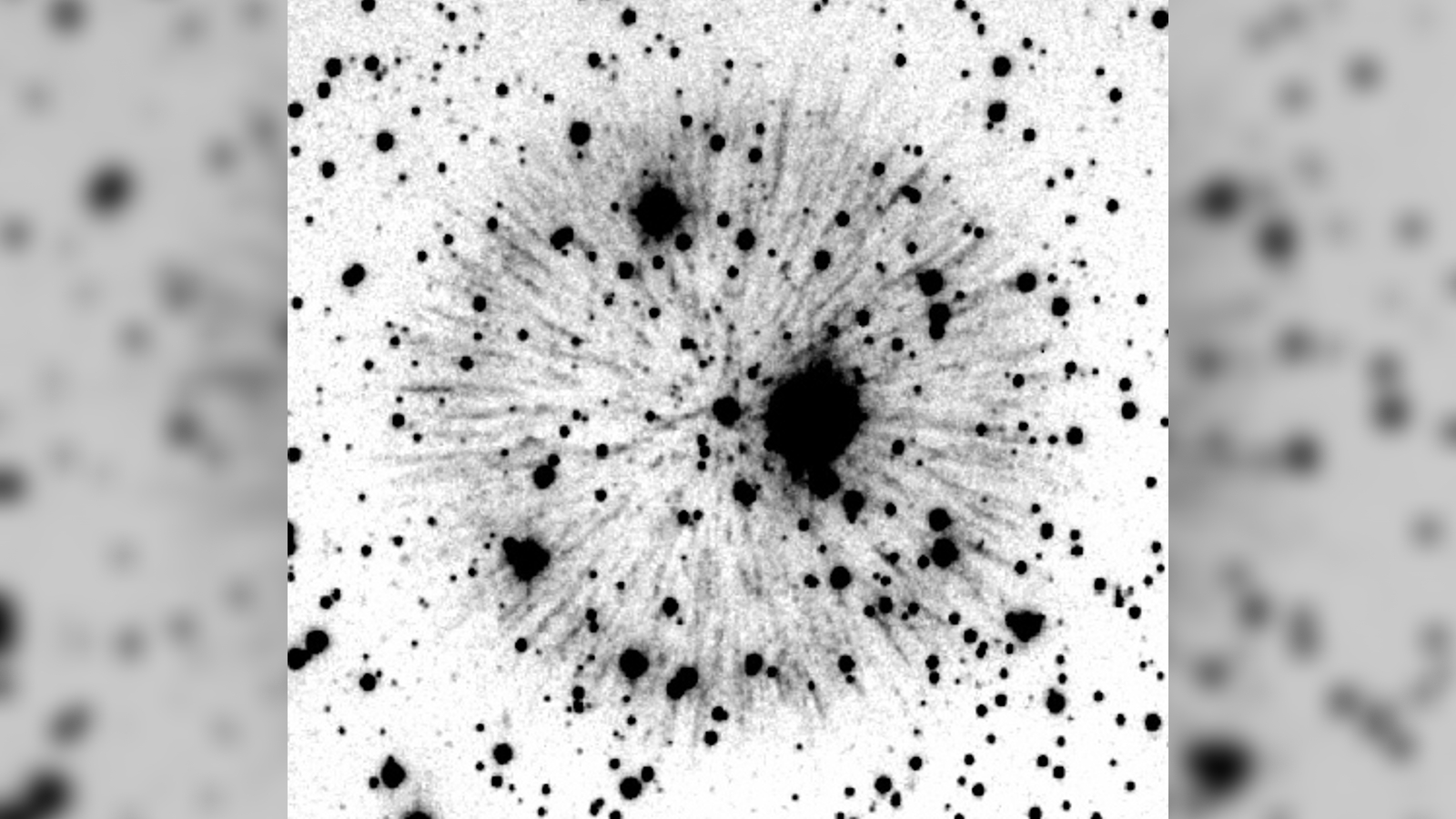

Previous observations of Pa 30 revealed a white dwarf star at the center of the nebula. The superdense object is all that remains of the exploding star that lit up the night sky 843 years ago. It burns intensely at around 360,000 degrees Fahrenheit (200,000 degrees Celsius), making it one of the hottest stars in the known universe. Normally, exploding stars get completely ripped apart when they go supernova, which makes this type of remnant a rarity.

In a new study, released Thursday (Oct. 24) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, astronomers created a new map of Pa 30 using the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI) — a spectrograph located near the summit of Hawaii's Mauna Kea volcano.

The resulting image was extremely detailed, capturing large filaments resembling "the petals of a dandelion" extending from the white dwarf to the edge of the nebula, the researchers wrote in a statement sent to Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By analyzing how the light given off by Pa 30 has shifted over time, the KCWI also traced how the nebula has changed shape, thus allowing the researchers to simulate a mini "3D movie" of the nebula's history. This is the first time this has ever been done with a supernova remnant, the researchers wrote.

One of the key takeaways from the animation is that the nebula is expanding at around 2.2 million mph (3.5 million km/h), which is around the same speed it would have hurled out debris during the initial supernova. "This means that the ejected material has not been slowed down, or sped up, since the explosion," study lead author Tim Cunningham, an astrophysicist at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in the statement.

Using this rate of expansion to look back in time, the team was able to "pinpoint the explosion to almost exactly the year 1181," which provided further proof that the guest star observed by astronomers back then came from Pa 30, Cunningham added.

The map also shows that Pa 30 is surprisingly asymmetrical compared with similar supernova remnants. There is no clear explanation for why the nebula would have grown wonky since the supernova, suggesting the asymmetry was caused by the initial explosion, the researchers wrote. However, it is unclear how this happened.

The new map "tells us a lot about a unique cosmic event that our ancestors observed centuries ago," study co-author Ilaria Caiazzo, a stellar astrophysicist at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, said in the statement. "But it also raises new questions and sets new challenges for astronomers to tackle next."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus