Atacama Telescope reveals earliest-ever 'baby pictures' of the universe: 'We can see right back through cosmic history'

New observations with the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile reveal the earliest-ever "baby pictures" of our universe, showing some of the oldest light we can possibly see.

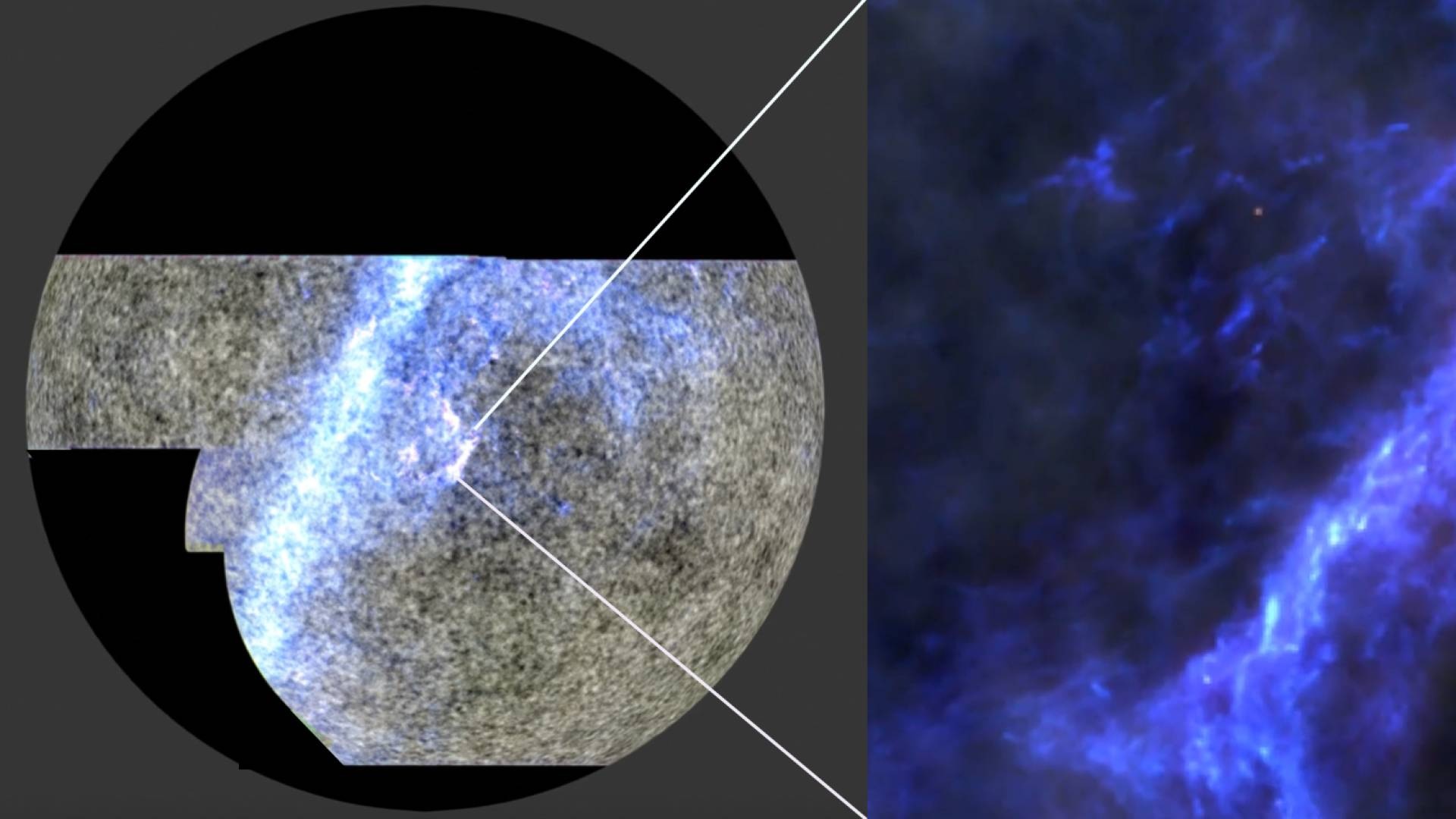

Astronomers have released the clearest images yet of the infant universe — and they confirm that the leading theory of the universe's evolution accurately describes its early stages.

The new images capture light that travelled for more than 13 billion years to reach the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) in Chile. They show the cosmos when it was just 380,000 years old — much like seeing baby pictures of our now middle-aged universe.

At that time, our universe emitted the cosmic microwave background as it emerged from its intensely hot, opaque state following the Big Bang, enabling space to become transparent. This faint afterglow marks the first accessible snapshot of our universe's infancy.

Rather than just the transition from dark to light, however, the new images reveal in high resolution the formation and motions of gas clouds of primordial hydrogen and helium, which, over millions to billions of years, coalesced into the stars and galaxies we see today.

"We can see right back through cosmic history — from our own Milky Way, out past distant galaxies hosting vast black holes and huge galaxy clusters, all the way to that time of infancy," Jo Dunkley, a professor of physics and astrophysical sciences at Princeton University in New Jersey, who led the ACT analysis, said in a statement.

"By looking back to that time when things were much simpler, we can piece together the story of how our universe evolved to the rich and complex place we find ourselves in today," she added in another statement.

These findings were submitted to the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics and presented at the American Physical Society meeting in California on Wednesday (March 19).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

About 1,900 "zetta-suns"

An analysis of these new images revealed that the observable universe extends almost 50 billion light-years in all directions from Earth. While the cosmos is estimated to be 13.8 billion years old, it has also expanded in that time, giving light and matter more room to spread out.

The results also suggest that the universe contains as much mass as 1,900 "zetta-suns," which is equivalent to almost 2 trillion trillion suns. Of this, only 100 zetta-suns come from normal matter — the kind we can see and measure, which is dominated by hydrogen, followed closely by helium.

Of the remaining 1,800 zetta-suns of material, 500 zetta-suns are dark matter, the invisible substance pervading the cosmos that is yet to be directly detected, while a whopping 1,300 zetta-suns come from the density of dark energy, a similarly mysterious phenomenon causing the universe to expand at an accelerating rate.

The high-definition observations provided scientists with a way to check how well the simple, prevailing model of the universe's evolution — known as the Lambda cold dark matter (Lambda CDM) — described the early universe. The data reveals no signs of new particles or unusual physics in the early universe, the scientists said.

"Our standard model of cosmology has just undergone its most stringent set of tests. The results are in and it looks very healthy," study co-author David Spergel, a theoretical astrophysicist and emeritus professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University, said in the statement. "We have tested it for new physics in many different ways and don't see evidence for any novelties."

The latest observations also provided additional measurements that reinforce previous findings, including a precise estimate of the universe's age and its rate of expansion, which is 67 to 68 kilometers per second per megaparsec (1 megaparsec is equivalent to about 3.2 million light-years). This data is among the final results from the now-decommissioned ACT, which completed its observations in 2022.

"It is great to see ACT retiring with this display of results," Erminia Calabrese, who is the director of research at Cardiff University's School of Physics and Astronomy and a lead author of one of the new studies, said in another statement. "The circle continues to close around our standard model of cosmology, with these latest results weighing in strongly on what universes are no longer possible," she added.

Meanwhile, the ACT's successor, the Simons Observatory, began operations earlier this week and captured the first of what astronomers hope will be many even more detailed images of the early universe.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.