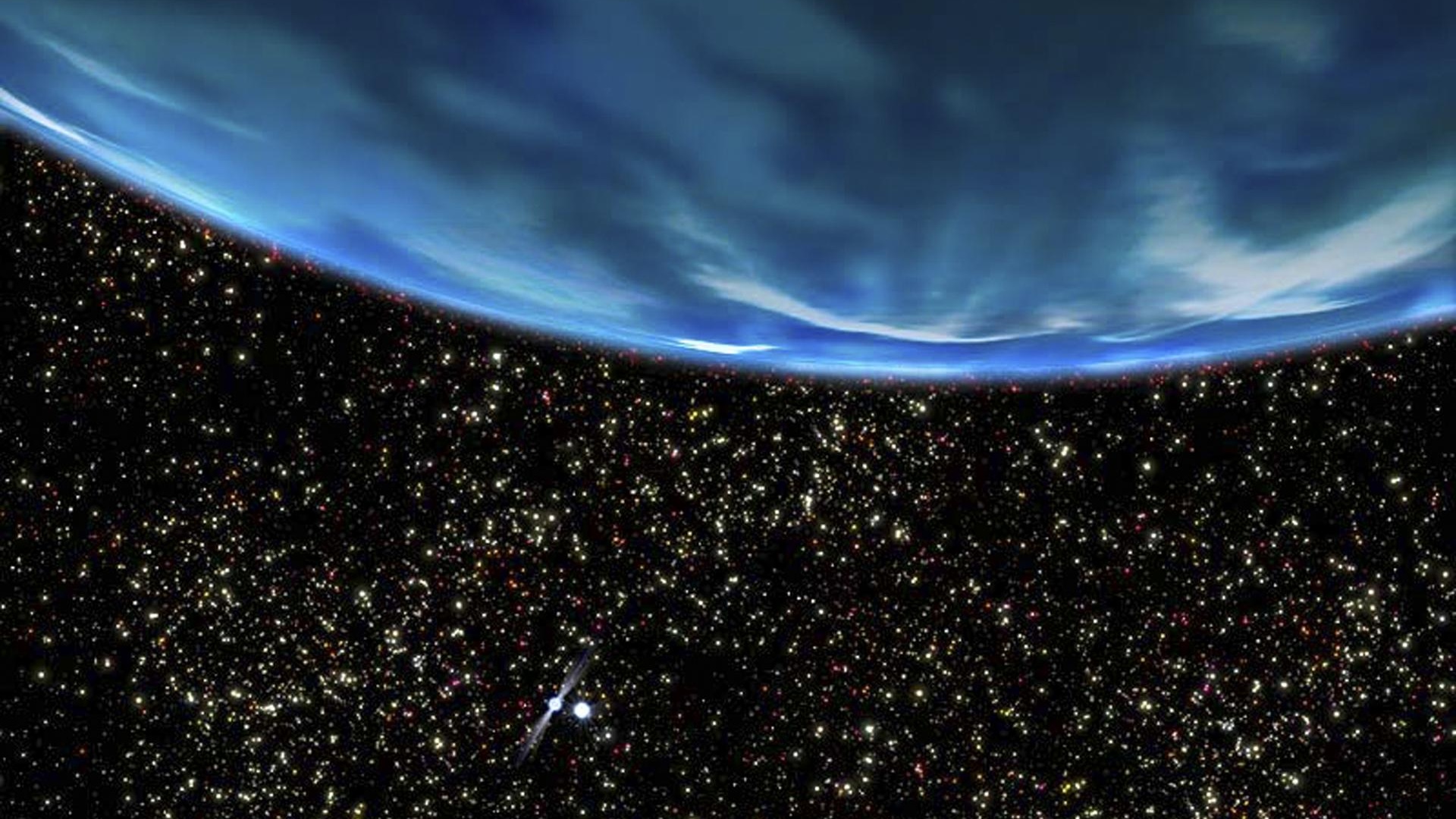

The universe's water is billions of years older than scientists thought — and may be nearly as old as the Big Bang itself

A new study suggests that water first appeared in the universe just a couple hundred million years after the Big Bang — meaning life could have evolved billions of years earlier than previously thought.

Water may have emerged in the universe far earlier than scientists thought — and it could mean that life could be billions of years older too, new research suggests.

Water is one of the most essential ingredients for life as we know it. But exactly when water first appeared has been a question of scientific interest for decades.

Now, new research suggests that water likely existed 100 million to 200 million years after the Big Bang — billions of years earlier than scientists previously predicted. The research was published March 3 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The early universe was dry because it was mainly filled with very simple elements, like hydrogen, helium and lithium. Heavier elements didn't develop until the first stars formed, burnt through their fuel supplies and ultimately exploded. Such stellar explosions, known as supernovas, acted like pressure cookers that combined lighter elements into increasingly heavier ones.

"Oxygen, forged in the hearts of these supernovae, combined with hydrogen to form water, paving the way for the creation of the essential elements needed for life," study co-author Daniel Whalen, an astrophysicist at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., said in a statement.

Related: 32 strange places scientists are looking for aliens

To determine when water first appeared, the researchers examined the most ancient supernovas, called Population III supernovas. Whalen and his team looked at models of two types of these early star remnants: core-collapse supernovas, when a large star collapses under its own mass; and pair-instability supernovas, when a star's interior pressure suddenly drops, causing a partial collapse.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that shortly after the Big Bang, both supernova types produced dense clumps of gas that likely contained water.

Overall, the amount of water in these gas clouds was probably pretty small — but it was concentrated in the areas where planets and stars were most likely to form, the team found. The earliest galaxies probably arose from these regions, which means that water may have already been in the mix when they formed.

"This implies the conditions necessary for the formation of life were in place way earlier than we ever imagined — it's a significant step forward in our understanding of the early Universe," Whalen said.

Observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, which is designed to view the universe's oldest stars, may help further validate these results.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.