'Baby' exoplanet, equivalent to 2-week-old infant, is the youngest alien world ever spotted — and it's orbiting a wonky star

A new study has identified an exoplanet that is just 3 million years old — around 1,500 times younger than Earth — alongside a misaligned protoplanetary disk that researchers cannot explain.

A "baby" exoplanet recently spotted relatively near to Earth is the youngest alien world ever seen, a new study suggests. Researchers say the rare sighting is linked to a mysteriously wonky proplanetary disk around the exoplanet's host star.

The newly discovered exoplanet, known as IRAS 04125+2902 b or TIDYE-1b, is a lightweight gas giant with a diameter slightly smaller than Jupiter's but around 0.4 times the mass of the solar system's largest planet. It orbits a protostar — a baby star still growing to its final size — located in the Taurus molecular cloud around 520 light-years from Earth and completes one rotation around the protostar every 8.8 days.

Based on the age of the protostar, which currently has a mass of around 70% that of our sun, TIDYE-1b can only be up to 3 million years old — around 1,500 times younger than Earth. If you were to compare the exoplanet's current age to a human lifespan, it would be a 2-week-old baby, researchers wrote in a statement.

Researchers described the baby exoplanet in a new study, published Nov. 20 in the journal Nature. The exoplanet was first spotted in data collected by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) as it continually passed in front of its host star.

"Discovering planets like this one allows us to look back in time, catching a glimpse of planetary formation as it happens," study lead-author Madyson Barber, a graduate student at The University of Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, said in the statement. "[It] helps us explore our place in the universe — where we came from and where we might be going."

Related: 32 alien planets that really exist

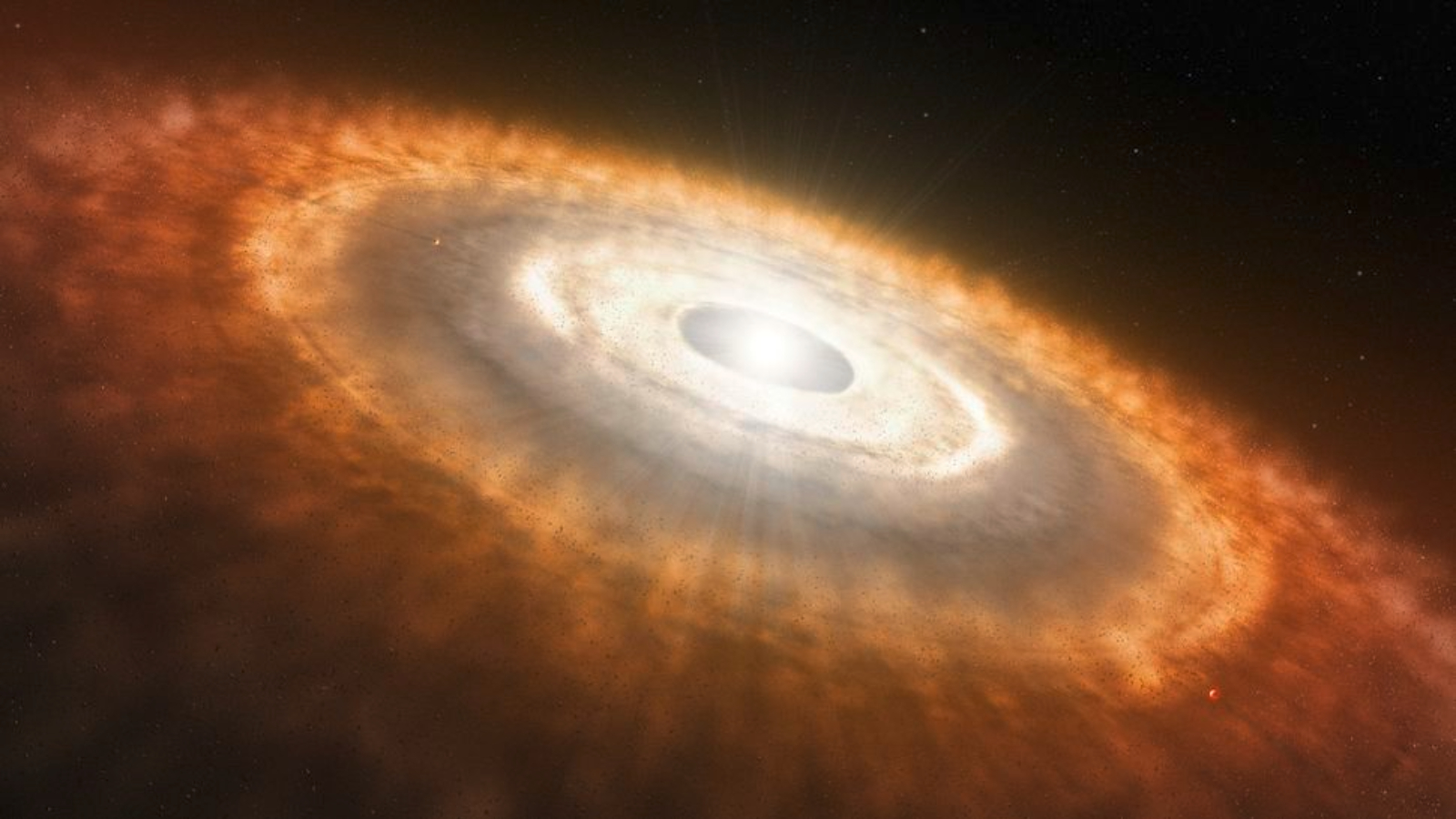

Exoplanets are normally only visible when they are more than 10 million years old, because, until then, they are obscured from sight by protoplanetary disks — the swirling rings of dust, gas and other planetary building blocks in which exoplanets form. But even then, only around a dozen exoplanets have been found that are less than 40 million years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, in this case, TIDYE-1b is not obscured by the star's protoplanetary disk.

"Planets typically form from a flat disk of dust and gas, which is why planets in our solar system are aligned in a 'pancake-flat' arrangement," study co-author Andrew Mann, a planetary scientist at UNC Chapel Hill, said in the statement. "But here, the disk is tilted, misaligned with both the planet and its star — a surprising twist that challenges our current understanding of how planets form." The disk is believed to be misaligned relative to the star by around 60 degrees, Mann added in another statement.

Researchers are not sure why the disk is misaligned or why TIDYE-1b is not located within this disk. One possible explanation is that the disk has been pulled out of place by a companion star, which orbits the protostar at a distance of around 635 astronomical units (635 times the distance between Earth and the sun). However, this may be unlikely given how far away the companion star is, researchers wrote.

The discovery helps to fill in gaps about how different worlds form. For example, experts believe that it took between 10 million and 20 million years for Earth to fully form, while it seemingly takes much less time for gas giants like TIDYE-1b to form. But there is still more to learn.

Researchers are planning to conduct follow-up studies on the juvenile world to assess if it is still accreting material from the disk, how its atmosphere compares to the surrounding disk material, and whether it's losing its upper atmosphere due to the influence of its host star.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.