12 strange reasons humans haven't found alien life yet

Scientists have been searching for evidence of extraterrestrial life for decades. So, where are all the aliens? Here are 12 intriguing theories ...

One night about 60 years ago, physicist Enrico Fermi looked up into the sky and asked, "Where is everybody?"

He was talking about aliens.

Today, scientists know that there are millions, perhaps billions of planets in the universe that could sustain life. So, in the long history of everything, why hasn't any of this life made it far enough into space to shake hands (or claws … or tentacles) with humans? It could be that the universe is just too big to traverse.

It could be that the aliens are deliberately ignoring us. It could even be that every growing civilization is irrevocably doomed to destroy itself (something to look forward to, fellow Earthlings).

Or, it could be something much, much weirder. Like what, you ask? Here are 12 unusual answers that scientists have proposed for the Fermi paradox.

Related: 'It's hard not to believe he saw something': Historian Greg Eghigian on how UFOs took over the world

We're looking in the wrong universe

Maybe we haven't found aliens because our universe isn't particularly conducive to life. Maybe Earth is an anomaly — a lucky blue dot adrift in a vast ocean of darkness and dead worlds. Maybe we'd have better luck looking for life in the next universe over.

That last idea is the premise of a 2024 study that assumes our cosmos is just one possible universe within an endless "multiverse" of realities, each one slightly different from the rest. To test whether our universe has the optimal conditions for life to emerge, the researchers compared star formation rates here to star formation rates in a host of hypothetical, parallel universes with different concentrations of matter and energy.

The main factor the team considered was a universe's density of dark energy — a mysterious force that drives the constant, accelerating expansion of the cosmos. A universe with too much dark energy would expand too quickly, scattering star-forming material and stunting the growth of large-scale structures like galaxy clusters. But in a universe with too little dark energy, gravity might become overwhelming, causing large structures to collapse before habitable planets had the chance to form.

The team's models revealed that the optimal density of dark energy within a universe would enable up to 27% of ordinary matter to turn into stars. But in our universe, only an estimated 23% of matter turns into stars — meaning there are fewer stars here than there could be and, as a result, fewer places for alien life to emerge. Better luck in the next universe!

Aliens don't live on planets

Every alien species needs a habitable planet to live on, right? Surprisingly, a 2024 study argues that may not always be the case.

In a paper accepted for publication in the journal Astrobiology, researchers proposed a scenario in which an alien colony could survive by floating freely in space, no planet required. It may sound wild, but it's not without real-world precedent; humans, for example, can live for hundreds of days without a planet while residing on the International Space Station (albeit with constant deliveries of crucial resources from their planet), and hardy tardigrades can survive the vacuum of space.

A theoretical planet-free alien colony would have to overcome many challenges, including a lack of resources, exposure to cosmic radiation and the vacuum of space, and access to enough sunlight. With this in mind, the researchers paint the picture of a species that could survive these trials: a free-floating colony of organisms measuring up to 330 feet (100 meters) across, encased in a thin, hard, transparent shell that could maintain a livable temperature and pressure through the greenhouse effect.

Finding such a species is a long shot, but it's not impossible. A free-floating alien colony could also explain why no intelligent aliens are answering our calls: They don't have a landline to use.

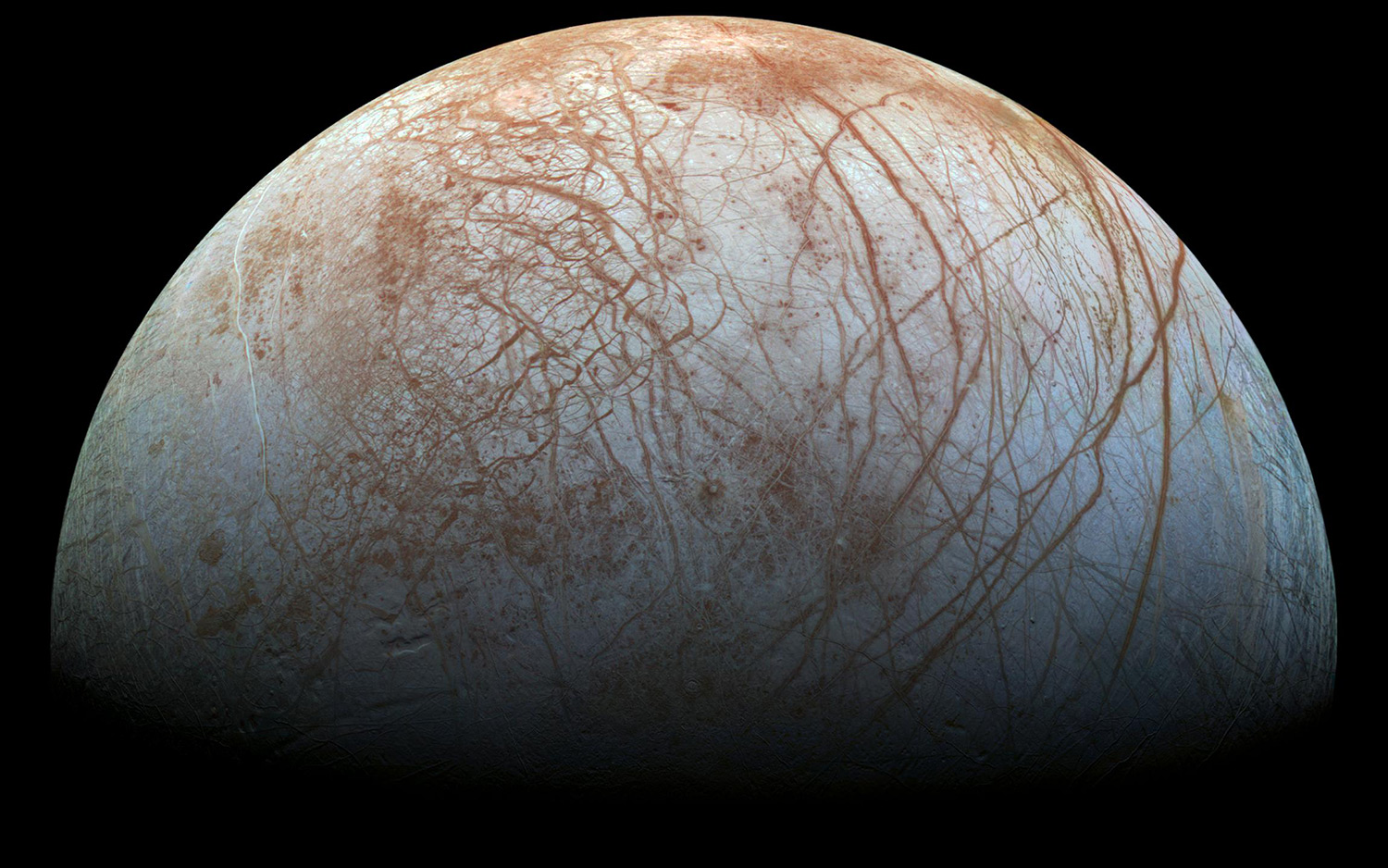

The aliens are hiding in underground oceans

If humans hope to converse with ET, we'll need to have a few icebreakers handy. No, seriously — alien life is probably trapped in secret oceans buried deep inside frozen planets.

Subsurface oceans of liquid water slosh beneath multiple moons in our solar system and may be common throughout the Milky Way, astronomers say. NASA physicist Alan Stern thinks clandestine water worlds like these could provide a perfect stage for evolving life, even if inhospitable surface conditions plague those plants. "Impacts and solar flares, and nearby supernovae, and what orbit you're in, and whether you have a magnetosphere, and whether there's a poisonous atmosphere — none of those things matter" for life that's underground, Stern told Space.com.

That's great for the aliens, but it also means we'll never be able to detect them just by glancing at their planets with a telescope. Can we expect them to contact us? Heck, Stern said — these critters live so deep, we can't even expect them to know that there's a sky over their heads.

Fortunately, NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft is on the way to one such moon to look for evidence of life up-close. The Clipper will arrive at Jupiter's frozen moon Europa in 2030.

The aliens are imprisoned on "super-Earths"

No, "super-Earth" is not Captain Planet's dorky cousin. In astronomy, the term refers to a type of planet with a mass up to 10 times greater than Earth's. Star surveys have turned up oodles of these worlds that could have the right conditions for liquid water. This means alien life could conceivably be evolving on super-Earths all over the universe.

Unfortunately, we'll probably never meet these aliens. According to a study published in 2018, a planet with 10 times Earth's mass would also have an escape velocity 2.4 times greater than Earth's — and overcoming that pull could make rocket launches and space travel near impossible.

"On more-massive planets, spaceflight would be exponentially more expensive," study author Michael Hippke, a researcher affiliated with the Sonneberg Observatory in Germany, previously told Live Science. "Instead, [those aliens] would be to some extent arrested on their home planet."

We're looking in the wrong places (because all aliens are robots)

Humans invented the radio around 1900, built the first computer in 1945 and are now in the business of mass-producing handheld devices capable of making billions of calculations per second. Full-blown artificial intelligence may be right around the corner, and futurist Seth Shostak said that's reason enough to reframe our search for intelligent aliens. Simply put, we should be looking for machines, not little green men.

"Any [alien] society that invents radio, so we can hear them, within a few centuries, they've invented their successors," Shostak said at the Dent:Space conference in San Francisco in 2016. "And I think that's important, because the successors are machines."

A truly advanced alien society may be completely populated by super-intelligent robots, Shostak said, and that should inform our search for aliens. Instead of focusing all our resources on finding other habitable planets, perhaps we should also look to places that would be more attractive to machines — say, places with lots of energy, like the centers of galaxies. "We're looking for analogues of ourselves," Shostak said, "but I don't know that that's the majority of the intelligence in the universe."

We've already found aliens (but are too distracted to realize it)

Thanks to pop culture, the word "alien" probably makes you envision a spooky humanoid with a big, bald head. That's fine for Hollywood — but these preconceived images of E.T. could sabotage our search for alien life, a team of psychologists from Spain wrote earlier this year.

In a small study, the researchers asked 137 people to look at pictures of other planets and scan the images for signs of alien structures. Hidden among several of these images was a tiny man in a gorilla suit. As the participants hunted for what they imagined alien life to look like, only about 30% noticed the gorilla man.

In reality, aliens probably won't look anything like apes; they may not even be detectable by light and sound waves, the researchers wrote. So, what does this study show us? Basically, our own imagination and attention span limit our search for extraterrestrialsy. If we don't learn to broaden our frames of reference, we could miss the gorilla staring us in the face.

Humans will kill all the aliens (or already have)

The closer we get to finding aliens, the closer we get to destroying them. That's one likely eventuality, anyway, said theoretical physicist Alexander Berezin.

Here's his thinking: Any civilization capable of exploring beyond its own solar system must be on a path of unrestricted growth and expansion. And as we know on Earth, that expansion often comes at the expense of smaller, in-the-way organisms. Berezin said this me-first mentality probably wouldn't end when alien life is finally encountered — assuming we even notice it.

"What if the first life that reaches interstellar-travel capability necessarily eradicates all competition to fuel its own expansion?" Berezin wrote in a paper posted in 2018 to the preprint journal arXiv.org. "I am not suggesting that a highly developed civilization would consciously wipe out other life-forms. Most likely, they simply won't notice, the same way a construction crew demolishes an anthill to build real estate because they lack incentive to protect it." (Whether humans are the ants or the bulldozers in this scenario remains to be seen.)

The aliens triggered climate change (and died)

When a population burns through resources faster than its planet can provide them, catastrophe looms. We know this well enough from the ongoing climate-change crisis here on Earth. So, isn't it possible that an advanced, energy-guzzling alien society might run into the same issues?

According to astrophysicist Adam Frank, it's not only possible but extremely likely. Earlier this year, Frank ran a series of mathematical models to simulate how a hypothetical alien civilization might rise and fall as it increasingly converted its planet's resources into energy. The bad news is that in three out of four scenarios, the society crumbled and most of the population died. Only when the society caught the problem early and immediately switched to sustainable energy did the civilization manage to survive. That means that, if aliens do exist, the odds are pretty high they'll destroy themselves before we ever meet them.

"Across cosmic space and time, you're going to have winners — who managed to see what was going on and figure out a path through it — and losers, who just couldn't get their act together, and their civilization fell by the wayside," Frank said. "The question is, which category do we want to be in?"

Aliens used clean energy, but still triggered climate change (and died)

A sufficiently advanced alien species will inevitably heat up its planet as its society and its energy needs grow. This could trigger runaway climate change, as humans are doing on Earth, and may doom those aliens to an early extinction. But what if the fast-growing alien society made an early switch to eco-friendly, renewable energy? Could that spare them, allowing the aliens to grow, thrive and expand throughout the cosmos without consequence?

Sorry, but no, according to a bleak theoretical study published to the preprint database arXiv in September 2024. The study found that an exponentially growing alien species using 100% renewable energy would still heat up their planet with waste heat, which is inevitably produced from any energy expenditure according to the second law of thermodynamics. This waste heat would continue to build up as long as the society's energy demands grew, eventually triggering disastrous climate change within 1,000 years of that society's industrial revolution.

If true, this means that an energy-guzzling alien race would likely never survive long enough to venture deep into the cosmos and set up shop on nearby planets. It's not only a sad outlook for aliens but an urgent wake-up call for Earth.

The aliens couldn't evolve fast enough (and died)

File another excuse under "the aliens are dead already" category. The universe may be teeming with hospitable planets, but there's no guarantee they'll stay that way long enough for life to evolve. According to a 2016 study from Australia National University, wet, rocky planets like Earth very unstable when they start their careers; if any alien life hopes to evolve and thrive on such a world, it has a very limited window (a few hundred million years) to get the ball rolling.

"Between the early heat pulses, freezing, volatile content variation and runaway [greenhouse gases], maintaining life on an initially wet, rocky planet in the habitable zone may be like trying to ride a wild bull — most life falls off," the study authors wrote. "Life may be rare in the universe not because it is difficult to get started, but because habitable environments are difficult to maintain during the first billion years.

Dark energy is splitting us apart

As we've already established, the universe is expanding. Slowly but surely, galaxies are moving farther apart, with distant stars appearing dimmer to us, all thanks to the pull of the mysterious, invisible substance that scientist call dark energy. Scientists speculate that within a few trillion years, dark energy will stretch the universe so much that Earthlings will no longer be able to see the light of any galaxies beyond our closest cosmic neighbors. That's a scary thought: If we don't explore as much of the universe as possible before then, such investigations may be lost to us forever.

"The stars become not only unobservable, but entirely inaccessible," Dan Hooper, an astrophysicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, wrote in a study earlier this year. That means we're on a serious deadline to find and meet any aliens out there — and to keep a step ahead of dark energy, we'll have to expand our civilization into as many galaxies as we can before they all drift away.

Of course, fueling that kind of growth won't be easy, Hooper said. It might involve rearranging the stars.

Twist ending: We ARE the aliens

If you left your house today, you saw an alien. The woman delivering mail? Alien. Your next-door neighbor? Nosy alien. Your parents and siblings? Aliens, aliens, aliens.

At least, that's one implication of the fringe astrobiology theory called the "panspermia hypothesis." In a nutshell, the hypothesis says that much of the life we see on Earth today didn't originate here but was "seeded" here millions of years ago by meteors carrying bacteria from other worlds.

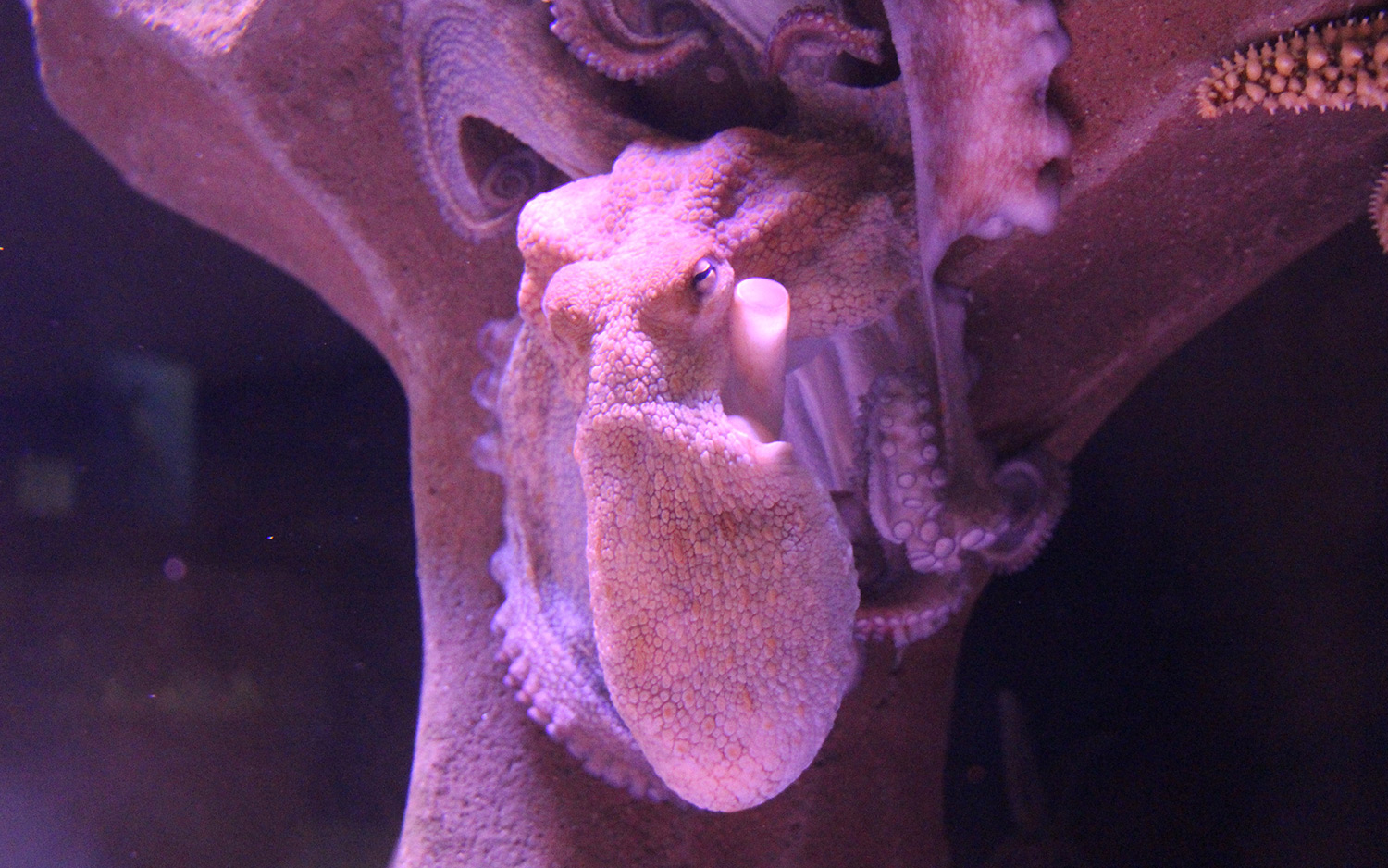

Proponents of this theory have variously suggested that octopi, tardigrades and humans were seeded here from other parts of the galaxy — but unfortunately, there's no real evidence to back up any of that. One big counterargument: If bacteria carrying human DNA evolved on another nearby planet, why haven't we found traces of humanity anywhere besides Earth? Even if this hypothesis turns out to be plausible, it still doesn't help us answer Fermi's nagging question … Where is everybody?

Editor's note: This article was originally published in July, 2018. It was updated on Dec. 2, 2024 with new studies and information.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.